Food irradiation is a process that carefully exposes food to ionizing radiation, such as X-rays or gamma rays, to eliminate harmful pathogens like Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter, which can cause foodborne illnesses. This exposure damages the DNA or RNA of microorganisms, ultimately leading to their destruction (Farkas, 2006; Matallana-Surget & Wattiez, 2013; Institute of Food Science and Technology, 2015).

In the food and agricultural industry, irradiation helps reduce storage losses, extend shelf-life, and enhance food safety by eliminating parasites and harmful microbes (Farkas, 2006). The most commonly used radiation sources—gamma rays, X-rays, and electron beams—generate high-energy charged atoms that disrupt microbial DNA and RNA structures (National Toxicology Program, 2011). Notably, irradiation can even be applied to large quantities of food, such as pallet-sized containers (Farkas, 2006).

Over recent decades, this preservation method has been widely used for various foods, including tubers, bulbs, grains, spices, meats, poultry, and seafood, to prevent microbial spoilage. Irradiation is considered an environmentally friendly and cost-effective technology that extends the shelf life of both raw and processed foods without compromising their taste, texture, or sensory qualities (Farkas, 2006; Indiarto & Qonit, 2020).

According to The Food Irradiation (England) Regulations 2009, any food or ingredient treated with ionizing radiation must be labeled as “irradiated” or “treated with ionizing radiation.” Additionally, a license is required to use this technology in food processing, and the appropriate radiation dose varies depending on the food type and characteristics.

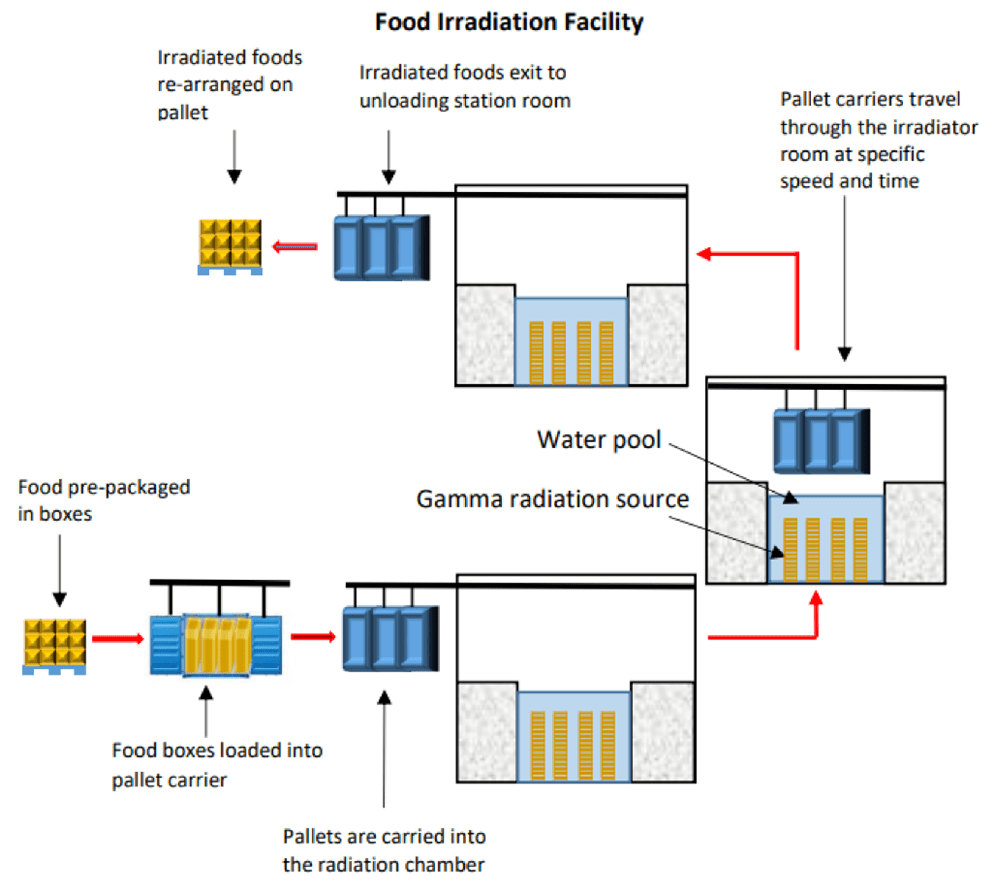

Ionizing sources and the process of food irradiation.

X-rays, gamma rays, and electron beams have very short wavelengths, allowing them to penetrate deep into thick layers of food (Farkas, 2006). This makes them highly effective in eliminating pathogens, parasites, and pests both on the surface and inside the food. X-rays are generated by directing electrons onto a thin gold plate, while gamma rays come from the neutron bombardment of cobalt-60 (60Co), a radioactive isotope used in nuclear reactors (Farkas, 2006; Balakrishnan et al., 2021).

Figure 1. A schematic flow-chart diagram of food irradiation process (Balakrishnan et al., 2021).

In industrial food irradiation, the process (Figure 1) is carefully controlled to ensure safety and effectiveness. First, food is packed into boxes and placed on a pallet. The radiation source, usually stored in a water-filled tank for safety, is lifted into a secure chamber with thick concrete walls to prevent radiation from escaping. The food pallets then move through the chamber, where they receive a precise dose of radiation for a set time. This exposure kills harmful bacteria and pests without the food ever touching the radiation source. Once the process is finished, the source is safely returned to the water tank, and the treated food is ready for handling and distribution (Mostafavi et al., 2010; Balakrishnan et al., 2021).

UK legislation and control of food irradiation.

According to The Food Irradiation (England) Regulations 2009, only seven categories of food are approved for irradiation. These include fruits (such as fungi, rhubarb, and tomatoes), vegetables (including pulses), cereals, bulbs and tubers (like onions, garlic, shallots, potatoes, and yams), poultry (including chickens, ducks, pigeons, geese, turkeys, and quails), fish and shellfish (such as crustaceans, eels, and mollusks), and dried aromatic herbs, spices, and vegetable seasonings. Table 1 provides details on the maximum allowed radiation doses for each food category in the UK.

Table 1: Maximum dose of ionising radiation permitted in the UK for different foods.

| S. No. | Foods Category | Dose of Ionising radiation/ kilogray (kGy) |

| 1. | Fruits | 2.0 |

| 2. | Vegetables | 1.0 |

| 3. | Cereals | 1.0 |

| 4. | Bulbs and tubers | 0.20 |

| 5. | Dried aromatic herbs, spices, and vegetable seasonings | 10.0 |

| 6. | Fish and shellfish | 3.0 |

| 7. | Poultry | 7.0 |

Source: The Food Irradiation (England) Regulations 2009 (2022).

Furthermore, if food has been treated with ionizing radiation, it must be labeled with the statement “Irradiated” or “Treated with ionising radiation”, along with the Radura symbol, which is the international sign for irradiated food. Additionally, if an irradiated ingredient is used in another food product, the label must include this information next to the ingredient in the ingredients list (The Food Irradiation (England) Regulations 2009, 2022).

Table 2: Various irradiation dose levels are used for different purposes in food.

| Food Items | Irradiation Dose | Purpose of use |

| Ginger, garlic, potatoes, onion, mango, banana, cereals, pulses, dehydrated vegetables, fresh pork, dried meat and fish. | Up to 1 kGy (Low dose) | To prevent sprouting, kills pathogens and pests associated with foods, slow ripening process and enhance shelf life of foods, fruits, and vegetables. |

| Fresh or frozen seafoods, raw or frozen poultry and meat, fish, grapes, strawberry, dehydrated vegetables. | 1-10 kGy (Medium dose) | To eradicate or eliminate food borne pathogens and pests, and hence reducing food spoilage. |

| Sterilized foods for immunocompromised patients | 10-50 kGy (High dose) | To Eliminating some disease-causing viruses from special meads used for immunocompromised people. |

Source: Shah et al. (2014).

Table 3: Different irradiation levels and their doses are used to extend the shelf life of various food items.

| Food | Radiation type | Radiation dose | Pathogens controlled | References |

| Legon-18 pepper powder | gamma radiation | 5 kGy | Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica Typhimurium | Odai et al. (2019) |

| Dairy cheese | X-ray | 3 kGy | Pseudomonas spp. and Enterobacteriaceae | Lacivita et al. (2019) |

| Idli | Gamma ray | 7.5 kGy | Aerobic bacteria, aerobic and anaerobic spores, and fungal growth | Mulmule et al. (2017) |

| Hamburgers | Electron beam | 2.04 kGy | Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Yersinia enterocolitica. | Cárcel et al. (2015) |

| Chilli Pepperand Sichuan pepper | Gamma rays | 4.00 and 5.00 kGy | Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica Typhimurium and Aspergillus niger | Deng et al. (2015) |

| Beef sausage patties | Gamma ray | 10 kGy | Pseudomonas fluorescens, psychrotrophs and Mesophiles | Park et al. (2010) |

| Chicken breasts | Electron beam | 1.8 kGy | Coliforms, E. coli, and Psychrotrophs, Salmonella and Campylobacter | Lewis et al. (2002) |

| Powdered black pepper | Gamma rays | 10.0 kGy | Bacillus, Clostridium, Micrococcus and Aspergillus flavus. | Emam et al. (1995) |

| Raw ground beef patties | Gamma ray | 2.5 kGy | Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus | Monk et al. (1994) |

Odai et al. (2019) found that treating Legon-18 Pepper (Capsicum annuum) powder with gamma radiation at 4°C for 8 weeks effectively inactivated pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella enterica Typhimurium (Table 3). In another study, Deng et al. (2015) irradiated Sichuan pepper (Zanthoxylum bungeanum) and chili pepper (Capsicum frutescens) with gamma rays at doses of 4 and 5 kGy after inoculating them with Aspergillus niger, E. coli, and Salmonella enterica Typhimurium. The results showed that both doses were highly effective in eliminating nearly all pathogens in the peppers. Irradiation doses up to 4 kGy have also been used to control pathogens in frozen seafood like prawns, frog legs, and shrimps. Similarly, Farkas (1998) observed that applying a 4 kGy dose of radiation to frozen Malaysian shrimps resulted in a reduction of 3 log-cycles in psychrotrophic and mesophilic colonies. Monk et al. (1994) demonstrated that a dose of 2.5 kGy of gamma radiation was effective in killing Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes by 4.10 log10 in both refrigerated and frozen ground beef. Lacivita et al. (2019) found that exposing dairy cheese to 3 kGy of x-ray extended its shelf life by more than 40 days, compared to just 10 days for the control sample. Similarly, Cárcel et al. (2015) reported that treating hamburgers with 2.04 kGy of electron beams extended their shelf life by 5 days compared to the control.

Koh and Button (2020) found that radiation not only sterilizes pathogens that cause food spoilage but also helps control various biological processes, such as delaying maturation, ripening, and sprouting, and slowing down aging. For example, irradiation treatment on green bananas delays ripening, prevents white potatoes from turning green, and inhibits sprouting in onions and potatoes at low doses ranging from 0.05 to 0.15 kGy. Additionally, radiation can trigger beneficial biochemical changes in foods, such as softening beans to reduce cooking time, speeding up the drying process for plums, and increasing juice yield from grapes (World Health Organisation, 1988). Another study showed that applying up to a 10 kGy dose of gamma-ray irradiation to beef sausage patties effectively reduced the population of Pseudomonas fluorescens, mesophiles, and psychrotrophs, while not affecting the sensory qualities of the patties, such as taste, color, or chewiness (Park et al., 2010).

Applications of Irradiation for food packaging.

In recent years, irradiation technology has also been used to treat packaging materials to ensure food safety. The food is first packaged in the right material, and then both the food and the packaging are exposed to the same dose, time, and type of radiation. This process helps sterilize any harmful bacteria, fungi, parasites, or insects that may be present on both the food and the packaging (Komolprasert et al., 2008). Chmielewski (2006) highlighted the importance of packaging materials, such as single-layer or multilayer films, in preventing recontamination of irradiated food. Multi-layered films or trays are particularly effective and are more likely to meet the toxicological safety requirements for radiation-treated pre-packaged foods. Similarly, Pentimalli et al. (2000) found that high doses of gamma irradiation (100 kGy for 30 milliseconds) had no significant impact on polystyrene packaging, as the aromatic rings in its structure absorb a large amount of radiation. This makes polystyrene suitable for packaging irradiated foods. However, polymers like polybutadiene and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene were significantly damaged by even low doses of gamma radiation (10 kGy). Additionally, irradiation treatment on glass packaging caused brown tinting, which affects the container’s appearance (Pentimalli et al., 2000).

Effects of Irradiation on food products.

Generally, irradiation treatment does not make food radioactive or significantly alter its nutritional quality and sensory properties. However, its impact on food depends on factors such as the preparation method, radiation type, duration, and dose used (Table 2). For example, processing food at high temperatures can create certain carcinogenic compounds, but these are not found in food after irradiation. Nutrients like carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and fat-soluble vitamins remain safe up to 10 kGy of ionizing radiation. Doses higher than 10 kGy may affect the food’s physical and chemical properties, leading to changes in its sensory characteristics (Miller, 2006). Additionally, some vitamins, such as vitamin A, thiamine (B1), vitamin C, and vitamin E, are more sensitive to radiation and can degrade during treatment (Dionísio et al., 2009).

Foods packaged in polymer-based materials are particularly vulnerable to chemical changes when exposed to ionizing radiation, potentially causing cross-linking (polymerization) or scission (degradation). Cross-linking typically occurs in a vacuum or inert environment, while the presence of oxygen or air in the packaging promotes chain scission (Vaclavik et al., 2008; Komolprasert et al., 2008). For example, when oxygen is present, radiation treatment may damage antioxidants or stabilizers, leading to the formation of radiolytic products. These products can migrate into the food, affecting its sensory and organoleptic qualities (Vaclavik et al., 2008).

Table 4: Advantage and disadvantages of using irradiation method in the food industries.

| Benefits | Limitations |

| Irradiation does not alter the textural, sensorial, and organoleptic attributes of foods, unlike heat and chemical treatments. | Irradiation process is not applicable to some foods, such as dairy products and eggs because it results in changes in texture and flavour. |

| It does not leave any harmful radioactive residues on foods. | It cannot eradicate or destroy pesticides and toxins that are already present in foods. |

| Radiation has high penetrating power to several layer and depth, and also effective for pre-packaged foods. | It is crucial to check the compliance of radiation processing to particular food commodity first in a laboratory. |

| Can control ripening and inhibit sprouting of fruits and vegetables. | Can alter the nutritional profile of some foods (beans), particularly thiamine and vitamin B |

| Environment friendly and time saving method. | License and safety precautions are must to use food irradiation technology. |

| Disinfect the hidden pests and pathogens present in the imported or exported food products. | Not effective against prions and viruses (Mad cow disease) |

| Extends the shelf life of unprocessed, minimally processed, and processed foods. | Lack of consumer choice, and expensive technology. |

Source: (Vaclavik et al., 2008; Miller, 2020; British Broadcasting Corporation, 2022).

Food Irradiation Hazards, Control Measures, and Consumer Behavior.

During food irradiation, food is exposed to ionizing radiation, which may cause slight changes in texture and appearance, but not as much as cooking or pasteurization would. However, there is still a risk of radioactive contamination from materials used in the process. For example, if an apple is irradiated, it remains safe to eat, but if it’s injected with cobalt-60, it becomes contaminated and unsafe. Additionally, water used in the process can become contaminated with gamma radiation isotopes. If there’s a leak in the system, radioactive water could seep into the ground, causing contamination in that area. Ionizing radiation is harmful to the human body, as it can damage or destroy cells, making it important to manage and control hazards during the irradiation process (Mostafavi et al., 2010; BBC, 2022). These hazards can be minimised by following proper precautions, such as:

a. Provide appropriate documents, brochures, guidelines, and rules for the safe production, processing, distribution, and handling of irradiated foods.

b. Avoid direct exposure of radiation to food.

c. Use technetium-99 shields to protect against radioactive sources when they are not in use.

d. Wear radiation protective clothing while working.

e. Limit the irradiation exposure time to food and monitor it using detector badges.

In fact, proper safety measures are essential to prevent contamination during the process. Once an object is contaminated with radiation, it can be very difficult to remove the contamination (BBC, 2022). This is why many consumers are afraid to eat irradiated foods, fearing that they may cause serious health issues due to radiation. However, this is a myth, as irradiated foods are treated in sealed chambers, preventing direct contact with radiation. In reality, over 55 countries around the world have approved food irradiation, and it is officially endorsed by the WHO and FAO, as there might be a negligible risk associated with using irradiation in food processing (Mostafavi et al., 2010; Maherani et al., 2016; Indiarto and Qonit, 2020; Balakrishnan et al., 2021).

TO conclude, food irradiation is a safe and effective method for extending shelf life and maintaining food stability by eliminating pathogens, pests, and parasites without affecting the food’s nutritional value or sensory qualities. This has led to increased use by food manufacturers to improve safety and quality. However, it is essential to follow proper safety regulations during the irradiation process to avoid contamination. Since food irradiation is driven more by market demands than consumer preferences, educating and raising awareness is crucial to help consumers accept irradiated foods.

References:

Balakrishnan, N., Yusop, S.M., Rahman, I.A., Dauqan, E. and Abdullah, A. (2021). Efficacy of Gamma Irradiation in Improving the Microbial and Physical Quality Properties of Dried Chillies (Capsicum annuum L.): A Review. Journal: Foods, 11(1), 1-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11010091

British Broadcasting Corporation (2022). Uses and dangers of radiation – AQA. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zp4vfcw/revision/1 (Accesses 17 June 2022).

Cárcel, J.A., Benedito, J., Cambero, M.I., Cabeza, M.C. and Ordóñez, J.A. (2015). Modeling and optimization of the E-beam treatment of chicken steaks and hamburgers, considering food safety, shelf-life, and sensory quality. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 96, 133-144. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbp.2015.07.006

Chmielewski, A.G. (2006). Packaging for food irradiation. Radiation processing, packaging, polymers, Food irradiation, Institute of Nuclear Chemistry and Technology, 3-11.

Deng, W., Wu, G., Guo, L., Long, M., Li, B., Liu, S., Cheng, L., Pan, X. and Zou, L. (2015). Effect of gamma radiation on Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica Typhimurium and Aspergillus niger in peppers. Food Science and Technology Research, 21(2), 241-245. doi: https://doi.org/10.3136/fstr.21.241

Dionísio, A.P., Gomes, R.T. and Oetterer, M. (2009). Ionizing radiation effects on food vitamins: a review. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 52(5), 1267-1278.

Emam, O.A., Farag, S.A. and Aziz, N.H. (1995). Comparative effects of gamma and microwave irradiation on the quality of black pepper. Zeitschrift für Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und Forschung, 201(6), 557-561. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01201585

Farkas, J. (1998). Irradiation as a method for decontaminating food: a review. International journal of food microbiology, 44(3), 189-204. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(98)00132-9

Farkas, J. (2006). Irradiation for better foods. Trends in food science and technology, 17(4), 148-152.

Institute of Food Science and Technology (2015). Food irradiation Available from: https://www.ifst.org/resources/information-statements/food-irradiation (Accessed 7 June 2022)

Indiarto, R. and Qonit, M.A.H. (2020). A review of irradiation technologies on food and agricultural products. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 9(1), 4411-4414.

Koh, J. and Button, P. (2020). Food irradiation is safe! Available from: https://foodmicrobiology.academy/2020/07/13/food-irradiation-is-safe/ (Accessed 7 June 2022).

Komolprasert, V., Bailey, A., Machuga, E. and Cianci, S. (2008). Regulatory Report: Irradiation of Food Packaging Materials. Available from: (https://www.fda.gov/food/ingredients-additives-gras-packaging-guidance-documents-regulatory-information/regulatory-report-irradiation-food-packaging-materials) (Accessed 16 June 2022).

Lacivita, V., Mentana, A., Centonze, D., Chiaravalle, E., Zambrini, V.A., Conte, A. and Del Nobile, M.A. (2019). Study of X-Ray irradiation applied to fresh dairy cheese. LWT – Food Science and Technology, 103, 186-191. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2018.12.073

Legislation.gov.uk (2022). The Food Irradiation (England) Regulations 2009 [online] Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2009/1584/made (Accessed 17 June 2022).

Lewis, S.J., Velasquez, A., Cuppett, S.L. and McKee, S.R. (2002). Effect of electron beam irradiation on poultry meat safety and quality. Poultry science, 81(6), 896-903. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/81.6.896

Maherani, B., Hossain, F., Criado, P., Ben-Fadhel, Y., Salmieri, S. and Lacroix, M. (2016). World market development and consumer acceptance of irradiation technology. Foods, 5(4), 1-21. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods5040079

Matallana-Surget, S. and Wattiez, R. (2013). Impact of solar radiation on gene expression in bacteria. Proteomes, 1(2), 70-86. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes1020070

Miller, B. (2020). 17 Major Advantages and Disadvantages of Food Irradiation. Available from: https://greengarageblog.org/17-major-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-food-irradiation (Accessed 16 June 2022).

Miller, R.B. (2006). Electronic irradiation of foods: an introduction to the technology. Springer Science and Business Media, 1-15.

Monk, J.D., Clavero, M.R.S., Beuchat, L.R., Doyle, M.P. and Brackett, R.E. (1994). Irradiation inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus in low-and high-fat, frozen and refrigerated ground beef. Journal of food protection, 57(11), 969-974. doi: https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-57.11.969

Mostafavi, H.A., Fathollahi, H. and Motamedi, F. (2010). Food irradiation: Applications, public acceptance and global trade. African Journal of Biotechnology, 9(20), 2826-2833.

Mulmule, M.D., Shimmy, S.M., Bambole, V., Jamdar, S.N., Rawat, K.P. and Sarma, K.S.S. (2017). Combination of electron beam irradiation and thermal treatment to enhance the shelf-life of traditional Indian fermented food (Idli). Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 131, 95-99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2016.10.014

National Toxicology Program (2011). Ionizing radiation: x-radiation and gamma radiation. Report on carcinogens: carcinogen profiles, 12, 237-240.

Odai, B.T., Tano-Debrah, K., Addo, K.K., Saalia, F.K. and Akyeh, L.M. (2019). Effect of gamma radiation and storage at 4° C on the inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica Typhimurium in Legon-18 pepper (Capsicum annuum) powder. Food Quality and Safety, 3(4), 265-272. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/fqsafe/fyz026

Park, J.G., Yoon, Y., Park, J.N., Han, I.J., Song, B.S., Kim, J.H., Kim, W.G., Hwang, H.J., Han, S.B. and Lee, J.W. (2010). Effects of gamma irradiation and electron beam irradiation on quality, sensory, and bacterial populations in beef sausage patties. Meat science, 85(2), 368-372. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.01.014

Pentimalli, M., Capitani, D., Ferrando, A., Ferri, D., Ragni, P. and Segre, A.L. (2000). Gamma irradiation of food packaging materials: an NMR study. Polymer, 41(8), 2871-2881. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(99)00473-5

Shah, M.A., Mir, S.A. and Pala, S.A. (2014). Enhancing food safety and stability through irradiation: A review. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences, 3(5), 371-378.

Vaclavik, V.A., Christian, E.W. and Campbell, T. (2008). Essentials of food science. New York: Springer, 42, 381-390. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9138-5

World Health Organization (1988). Food Irradiation: A technique for preserving and improving the safety of food. Published by the World Health Organization in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 5-84.

Leave a comment