Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescence assay works by detecting ATP produced by pathogens through a physicochemical reaction. ATP, often referred to as the energy currency of cells, is a key organic molecule responsible for storing and transferring energy in all living organisms. The presence of ATP in food and on food preparation surfaces indicates possible microbial contamination, as well as the presence of enzymes and allergens (Dunn & Grider, 2021; Masia et al., 2021).

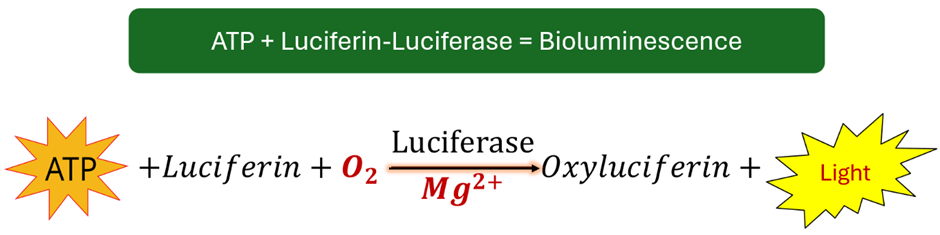

Figure 1: Simplified reaction process illustrating ATP and luciferin as reactants for luciferase to produce light.

This assay, also known as an energy measurement technique, relies on ATP’s role in oxidizing luciferin into oxyluciferin, producing light (Bioluminescence) with the help of the enzyme luciferase (which facilitates bioluminescence) (Figure 1). During this process, ATP is converted into AMP, releasing PPi and emitting a chemiluminescent signal within the wavelength range of 470-700 nm (Eed et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2018; Masia et al., 2021). The reaction is shown in the equation below.

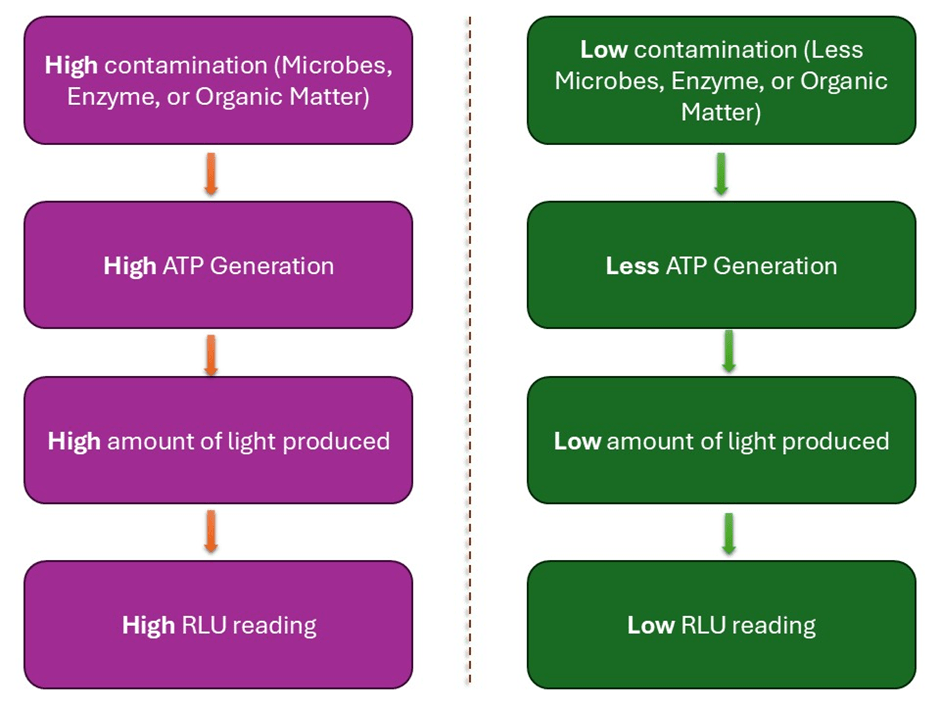

The level of bioluminescence is measured using a device called a luminometer and is expressed in relative light units (RLU). RLU results are indirectly related to CFU, as RLU is proportional but not equivalent to CFU. Since the amount of luminescence is directly proportional to ATP concentration (Figure 2), RLU can be converted into RLU per mole of ATP, providing insights into total cell viability in food samples and/or food contact surfaces (Singh et al., 2018; Ali et al., 2020).

Figure 2: The relationship between contamination, ATP production, and the RLU reading on the luminometer.

This method is highly sensitive, capable of detecting as little as 0.8–100 amol (1 amol = 1 × 10⁻¹⁸ mol) of intracellular ATP from living microbial cells within an hour, without requiring a culture step (Ishimaru et al., 2021). Kim et al. (2018) demonstrated that ATP bioluminescence measurement after photothermal lysis of targeted bacteria, using gold nanorods and NIR irradiation, is a highly selective and sensitive detection technique. This approach delivers results within 36 minutes, with only a short incubation period (30 minutes) and a 6-minute NIR irradiation step.

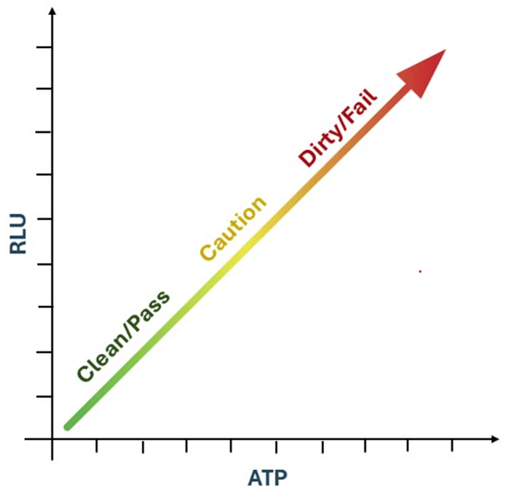

Figure 3: Relationship Between ATP and RLU as Indicators of Cleanliness or Contamination Levels.

In fact, higher RLU in an ATP test correspond to higher levels of ATP, which serve as an indicator of greater contamination, and vice-versa (Figure 3). In addition, high efficiency, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity are crucial for obtaining precise and reliable results in ATP bioluminescence testing. Sensitivity can be further enhanced by increasing ATP levels through heat treatment, which helps release bound ATP from microbial cells and organic residues. This process improves the detection of low levels of contamination, ensuring more accurate hygiene monitoring. For example, heating food samples at 95°C for 10 minutes improves detection, while exposing bacterial samples to 50°C for 10 minutes increases RLU values by 2 to 3 times (Lee et al., 2017).

Table 1: An overview of commercial ATP Bioluminescence assay devices coupled with luminometers for food and beverages analysis (Source: Rijal, 2023).

| Supplier Name | Luminometer Type | Method | Suitability | Application | LOD/ Detection Range | Incubation Time |

| 3M | 3M™ Clean-Trace™ Luminometer | Surface swab, liquid and solid foods (Single use) | Foodborne pathogens and enzymes | Fruits, vegetables, grain, pet foods, processed foods and seafoods | 10 RLU (1.3 fmoles ATP) | 4 hours |

| Charm Sciences Inc | NovaLUM® II Luminometer | Swab | Coliforms and hydrogen sulfide producing EB, allergens and pesticides | Dairy products, foods, grains, feed, hospitality and water treatment | 1.0 fmoles ATP | 30 minutes |

| Neogen | Neogen® AccuPoint Luminometer | Surface Swab, food and beverages | EB, TVC, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Lactobacillus plantarum, Enzymes, and allergens | Surfaces, beverages, food and liquid samples | 10 fmoles ATP | Real time testing |

| Hygiena™ | EnSURE™ Touch | Surface swab, liquid, and solid foods (Single use) | Coliforms, EB, TVC, Enzymes, allergens and mycotoxins | Surfaces, beverages, and food samples | Ultrasnap kit-1.0 fmols ATP | 6-8 hours |

| Surfaces, foods and beverages | SuperSnap kit- 0.17 fmols ATP | 6-8 hours | ||||

| R-Biopharm | Lumitester™ PD-30 | Surface swab, liquid and solid foods (Single use) | Salmonella, E. coli, Campylobacter, allergens, viruses, and bacterial toxins | Fluids, dry and moist surfaces | 10 RLU (0 to 999999 RLUs) | 15 minutes |

| Pall Corporation | Pall Pallchek Luminometer Trans Illuminator | liquid and solid foods (Multiwell-plates) | EB, P. aeruginosa S. aureus, and Enzymes | Food and beverages | 10 – 100 CFU | 2-3 hours |

| ThermoFisher Scientific | Fluoroskan™ FL Microplate Luminometer | Multiwell-plates | Cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, nucleic acid quantitation, gene assays, immunoassays, & enzyme activity. | Food, beverages, and surfaces | 10 amol ATP/well using flash reaction | Real time testing |

A variety of rapid ATP bioluminescence assay kits are available on the market, designed for easy and portable use in quickly screening food samples (Table 1). These kits enable high-throughput, automated detection of foodborne pathogens based on ATP bioluminescence. In this method, food and beverage samples can be tested directly in detection tubes, either with or without dilution. However, when monitoring surface hygiene, food production surfaces, tools, and equipment must first be swabbed before processing with the luciferin-luciferase complex. For the ATP bioluminescence test of food contact surface areas, swab a 10 x 10 cm (4 x 4 in) area. Move the swab side to side and up and down while rotating the tip to ensure thorough collection and complete coverage of the targeted area.

Several companies have developed highly specific and sensitive luminometers and detection tools. For instance, 3M offers ATP-based test devices such as the 3M™ Clean-Trace™ luminometer, 3M™ Clean-Trace™ total ATP test device, and surface ATP test device, which detect ATP levels with a limit of detection (LOD) of 1.3 femtomoles (fmol) of ATP (1 fmol = 10⁻¹⁵ moles). Similarly, Neogen® AccuPoint Luminometer uses an advanced ATP testing tube with a half-inch diameter, capable of measuring both total ATP and microbial ATP depending on the swab type, with an LOD of about 10 fmols ATP.

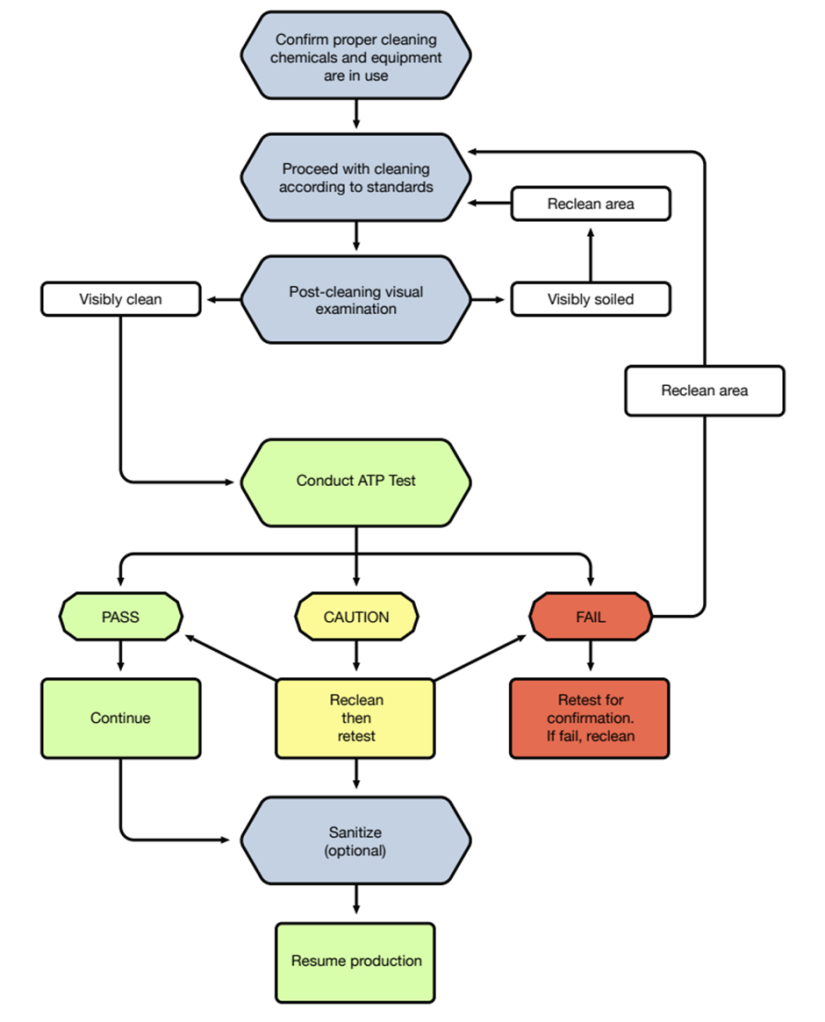

Figure 4: Recommended Cleaning and Corrective Action Procedures (Source: Hygiene Monitoring Guide).

Hygiena™ provides Ultrasnap and Supersnap swab kits, with LODs of 1.0 fmol and 0.17 fmol ATP, respectively. These kits can even detect as low as 1 CFU/ml after sample incubation and are AOAC-certified (Bottari et al., 2015). Hygiena™ also offers the Hygiena™ EnSURE™ Touch, a portable, handheld device with Wi-Fi and cloud storage access. This system measures both total ATP and microbial ATP levels, with low variability (5-12%) across different ATP concentrations (20-2,000 fmol). A low coefficient of variation (CV%) indicates more consistent and reliable results, with values closer to 0% is desirable. Refer to Figure 4 for the recommended cleaning and corrective action procedures outlined in the Hygiene Monitoring Guide.

These commercial ATP bioluminescence assay kits are widely used in the food and beverage industry, healthcare sector, canteens, and service industries due to their ability to provide immediate on-site results. However, a key limitation of this technique is that it cannot distinguish whether the detected ATP originates from harmful or beneficial bacteria (Kim et al., 2018).

Applications and benefits of ATP Bioluminescence rapid test kits.

The ATP Bioluminescence rapid test system provides fast and accurate results, making it an ideal point-of-care test for industries and developing countries. Using a luminometer, it delivers results in a readable format within few minutes to hours, significantly faster than traditional enumeration methods (Dilek, 2019; Zheng et al., 2019). Thanks to its compact and portable setup—including an incubator, luminometer, and test devices—this system is easy to transport and can be used for detecting pathogenic contamination in food, seeds, and food production surfaces. It can also detect high contamination levels without the need for serial dilutions, saving both time and sample quantity during analysis. With proper training, the equipment is simple to operate, making it especially valuable during food poisoning outbreaks. It can quickly identify total viable count, coliforms, allergens, and other harmful foodborne bacteria, allowing for immediate preventive actions (Nayak, 2014).

Traditional enumeration methods assume that a single bacterial colony originates from one cell, but this is not always accurate—some bacteria naturally form pairs, chains, or clusters, leading to an underestimation of the actual population (Nieto et al., 2022). In such cases, the MicroSnap device offers a more reliable alternative for bacterial detection.

Factors Contributing to False Results in ATP Bioluminescence Detection.

It is not uncommon for the system to produce false positive or false negative results. Several factors can influence variations in cell count, including differences in microbial cell size, cell development stages, background noise from the detection device, and ATP naturally present in food. Other factors such as chemical interference, contamination during sample preparation, and enumeration time can also contribute to discrepancies. The ATP content in food may impact the total ATP detected by the luciferase enzyme, leading to an overestimated count (Aon et al., 2014; Nayak, 2014; Arroyo et al., 2017). Additionally, background noise from the system, including electrical and chemical interference from food impurities and surfaces, may also result in an inflated cell count (Meighan, 2014; Meighan et al., 2016).

To conclude, The presence of ATP on surfaces signals inadequate cleaning and potential contamination from organic debris and bacteria. Food residues not only indicate poor sanitation but also create environments where bacteria can thrive, interfere with disinfectants, and contribute to biofilm formation. Additionally, allergenic food residues increase the risk of cross-contact. However, ATP tests cannot directly detect bacteria or allergenic proteins. Effective use of these tests requires a thorough understanding of their applications, pass-fail limits, and performance variations. Traditional ATP tests face limitations due to ATP breakdown into ADP and AMP, making residue detection challenging. To address this, the total adenylate (A3) test was developed, which detects ATP, ADP, and AMP, improving the identification of food residues. When combined with microbial culture and allergen testing, the A3 test enhances contamination detection and supports better hygiene management (Bakke, 2022).

References

Ali, A.A., Altemimi, A.B., Alhelfi, N. and Ibrahim, S.A. (2020). Application of biosensors for detection of pathogenic food bacteria: a review. Biosensors, 10(6), p.58. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/bios10060058

Aon, M.A., Bhatt, N. and Cortassa, S.C. (2014). Mitochondrial and cellular mechanisms for managing lipid excess. Frontiers in physiology, 5, p.282. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2014.00282

Arroyo, M.G., Ferreira, A.M., Frota, O.P., Rigotti, M.A., de Andrade, D., Brizzotti, N.S., Peresi, J.T.M., Castilho, E.M. and de Almeida, M.T.G. (2017). Effectiveness of ATP bioluminescence assay for presumptive identification of microorganisms in hospital water sources. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1), pp.1-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2562-y

Bakke, M., 2022. A comprehensive analysis of ATP tests: practical use and recent progress in the total adenylate test for the effective monitoring of hygiene. Journal of food protection, 85(7), pp.1079-1095. https://doi.org/10.4315/jfp-21-384

Bottari, B., Santarelli, M. and Neviani, E. (2015). Determination of microbial load for different beverages and foodstuff by assessment of intracellular ATP. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 44(1), pp.36-48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2015.02.012

Dilek, Ç.A.M. (2019). Lateral flow assay for Salmonella detection and potential reagents, in M. Ranjbar, M. Nojomi, M.T. Mascellino (eds.) In New Insight into Brucella Infection and Foodborne Diseases. London, UK: IntechOpen, pp.107-117. doi: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88827

Dunn, J. and Grider, M.H. (2021). Physiology, adenosine triphosphate. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553175/ (Accessed 06 March 2025).

Eed, H.R., Abdel-Kader, N.S., El Tahan, M.H., Dai, T. and Amin, R. (2016). Bioluminescence-sensing assay for microbial growth recognition. Journal of Sensors, pp.1-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1492467

Ishimaru, M., Noda, H., Matsumoto, E., Koshi, H. and Otake, H. (2021). Comparative study of rapid ATP bioluminescence assay and conventional plate count method for development of rapid disinfecting activity test. Luminescence, 36(3), pp.826-833. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/bio.4014

Kim, S.U., Jo, E.J., Noh, Y., Mun, H., Ahn, Y.D. and Kim, M.G. (2018). Adenosine triphosphate bioluminescence-based bacteria detection using targeted photothermal lysis by gold nanorods. Analytical chemistry, 90(17), pp.10171-10178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00254

Lee, J., Park, C., Kim, Y. and Park, S. (2017). Signal enhancement in ATP bioluminescence to detect bacterial pathogens via heat treatment. BioChip Journal, 11(4), pp.287-293. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13206-017-1404-8

Liu, J.T., Luo, J., Liu, X. and Cai, X. (2014). Development of a rapid optic bacteria detecting system based on ATP bioluminescence. In International Symposium on Optoelectronic Technology and Application 2014: Laser and Optical Measurement Technology; and Fiber Optic Sensors, Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, 9297, pp.42-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2069489

Masia, M.D., Dettori, M., Deriu, G.M., Bellu, S., Arcadu, L., Azara, A., Piana, A., Palmieri, A., Arghittu, A. and Castiglia, P. (2021). ATP bioluminescence for assessing the efficacy of the manual cleaning procedure during the reprocessing of reusable surgical instruments. In Healthcare, 9(3), p.352. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030352

Meighan, P. (2014). Validation of the MicroSnap Coliform and E. coli Test System for Enumeration and Detection of Coliforms and E. coli in a Variety of Foods. Journal of AOAC International, 97(2), pp.453-478. doi: https://doi.org/10.5740/jaoacint.13-361

Meighan, P., Smith, M., Datta, S., Katz, B. and Nason, F. (2016). The Validation of the MicroSnap Total for Enumeration of Total Viable Count in a Variety of Foods. Journal of AOAC International, 99(3), pp.686-694. doi: https://doi.org/10.5740/jaoacint.16-0016

Nayak, R.S. (2014). Comparison of the novel MicroSnap™ Coliform test kit with the 3M™ Petri-films (Unpublished master’s dissertation). University of Birmingham, Birmingham, England. doi: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2669.4244

Nieto, C., Vargas-Garcia, C., Pedraza, J. and Singh, A. (2022). Cell size regulation and proliferation fluctuations in single-cell derived colonies. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.05.498901

Singh, A., Tiwari, A., Bajpai, J. and Bajpai, A.K. (2018). 3. Polymer-based antimicrobial coatings as potential biomaterials: From action to application. Handbook of Antimicrobial Coatings, pp.27-61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811982-2.00003-2

Zheng, L., Cai, G., Qi, W., Wang, S., Wang, M. and Lin, J. (2019). Optical biosensor for rapid detection of Salmonella typhimurium based on porous gold@ platinum nanocatalysts and a 3D fluidic chip. ACS sensors, 5(1), pp.65-72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.9b01472

Robin Rijal, with a strong background in Agricultural Science and Food Science & Technology, has developed expertise in plant pathology, molecular biology, and food science. He is deeply passionate about exploring innovative trends and technologies in food and agriculture, aiming to contribute to sustainable farming practices and enhanced food production.

Leave a comment