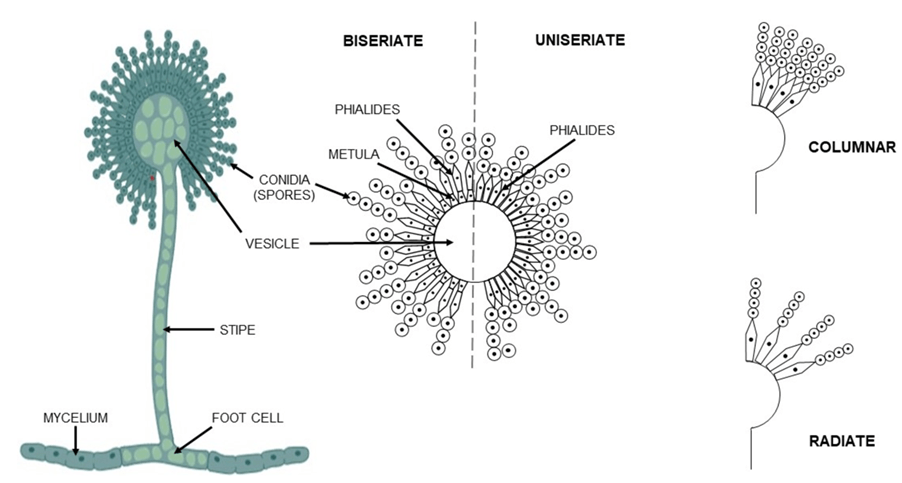

Around 300–400 fungal species produce mycotoxins, which are toxic metabolites that contaminate agricultural products and pose significant health risks to livestock, poultry, and humans, even at extremely low concentrations (Latham, 2023). Among them, aflatoxins produced by Aspergillus species (Figure 1) are particularly dangerous, contaminating cereals, oilseeds, spices, and nuts during both cultivation and storage. Aflatoxins, highly toxic secondary metabolites produced by certain Aspergillus species, rank among the top five agriculturally significant mycotoxins. These toxins primarily contaminate cereals, oilseeds, spices, and nuts during both field cultivation and storage. Among the 13 naturally occurring aflatoxins, types B1, B2, G1, and G2 are the most potent. Aflatoxin M1 and M2, derivatives of B1 and B2, can even seep into the milk of animals consuming contaminated feed, posing severe health risks such as liver cancer in vertebrates. The production of aflatoxins is regulated by a complex genetic pathway, primarily involving the aflR gene, along with other genes like aflS, aflP, and aflQ. Interestingly, not all Aspergillus species carrying these genes produce aflatoxins, highlighting the intricate genetic and evolutionary dynamics of these fungi (Sharma et al., 2025).

Figure 1. The morphological variations of Aspergillus species, including uniseriate or biseriate arrangements (Sharma et al., 2025).

Health Impacts of Aflatoxin Exposure

Acute exposure to high aflatoxin concentrations can trigger severe, life-threatening conditions including sudden liver failure (Fulminant hepatic necrosis) and rapid skeletal muscle breakdown (Rhabdomyolysis). However, the greater public health concern lies in chronic low-level exposure, which frequently leads to progressive liver damage. Over time, this manifests as liver cirrhosis and often develops into hepatocellular carcinoma, with emerging evidence linking prolonged exposure to gallbladder carcinoma as well. Emerging research reveals that aflatoxin exposure in children has particularly devastating consequences, including significant growth stunting, impaired nutrient absorption leading to multiple deficiencies, cognitive and developmental delays, and compromised immune function. As potent hepatotoxins, aflatoxins primarily attack the liver, with early toxicity symptoms appearing as nonspecific complaints like fever, fatigue, and loss of appetite that progress to abdominal pain, vomiting, and hepatitis. The insidious nature of chronic exposure proves far more dangerous due to its immunosuppressive and carcinogenic effects (Kumar et al., 2017; Dhakal et al., 2023)

Global occurrence and distribution of Aspergillus species.

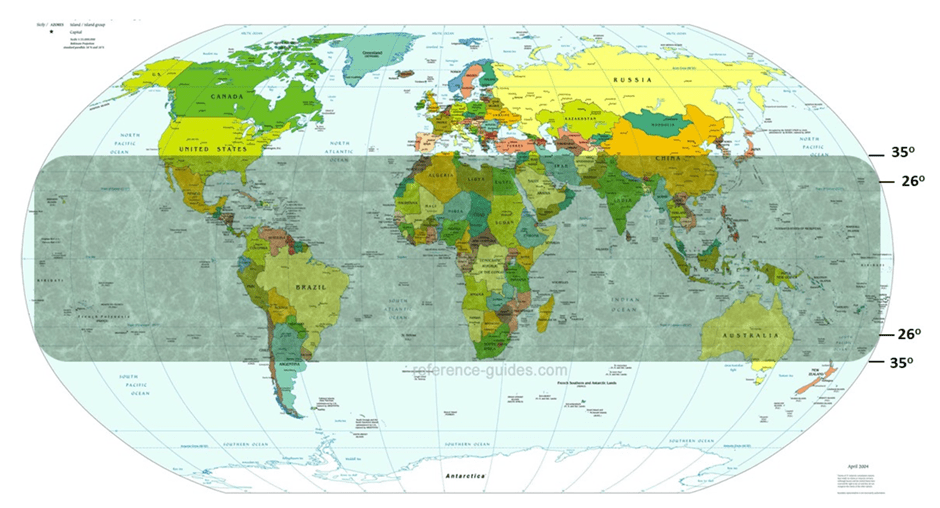

The expression of the aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster is influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include the crop’s genotype, nutrient composition, and water activity (aw), while extrinsic factors encompass temperature, humidity, environmental stresses, and geographical location. Generally, aflatoxin contamination is more prevalent in warm and humid climates, which are common in regions such as parts of Africa, Asia, India, the southern USA, South America, and certain areas of Australia (Mannaa and Kim, 2017; Dövényi-Nagy et al., 2020). The fungi A. flavus and A. parasiticus, which are most abundant between latitudes 26° and 35° in both hemispheres (Figure 2), are major contributors to aflatoxin production in these regions (Sharma et al., 2025).

Figure 2. The global distribution of Aspergillus species, with the intensity of the grey hue varying by latitude, between the two hemispheres (Sharma et al., 2025).

The optimal aw for the growth of Aspergillus species is 0.99, although the minimum required for growth is not precisely defined. Figure 1 displays the characteristic signs of Aspergillus contamination (Figure 3). From several studies it has been reported that Aspergillus species cannot proliferate or produce aflatoxins at an aw of 0.82 at 25°C (FAO, 2001). The lowest aw for aflatoxin production in A. flavus isolates is approximately 0.87 (Pitt and Miscamble, 1995), while Marín et al. (2024) propose that the minimum aw for aflatoxin biosynthesis is 0.83 at 27°C. Similarly, Aspergillus species grow between 10–43°C, with an optimal growth range of 30–37°C (Liu et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2025). Aflatoxin production occurs at temperatures ranging from 15–37°C, with the highest levels produced between 20–30°C (FAO, 2001). Lahouar et al. (2016) found that aflatoxin B1 accumulation did not occur at aw ≤0.91 in sorghum at 15°C. Similarly, Liu et al. (2017) observed that A. flavus growth was slower at temperatures ≤20°C or aw ≤0.85 in shelled peanuts, with the highest AFB1 levels at aw 0.96 and 28°C, due to higher expression of aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis genes and LaeA at this temperature and aw.

Figure 3. Aspergillus and Aflatoxins contamination in maize and peanuts (WikiFarmer).

The primary aflatoxin-producing species are A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius, while A. arachidicola, A. minisclerotigenes, and A. saccharicola have also been documented as aflatoxigenic. In contrast, A. niger, A. oryzae, A. fumigatus, and A. wentii are non-aflatoxin-producing species. These fungi, although incapable of producing aflatoxins, can produce other mycotoxins and bioactive compounds. For example, A. fumigatus produces immunosuppressive mycotoxins like fumagillin, gliotoxin, and fumitremorgin A (Kamei and Watanabe, 2005). Similarly, A. niger is associated with the production of fumonisins and ochratoxin A (Soares et al., 2013). A. oryzae, A. sojae, and A. wentii are considered biologically safe and are widely used in the industrial production of enzymes, fermented foods, and beverages such as soybean paste, soy sauce, and rice wine (Sharma et al., 2025). Additionally, A. terreus, a non-aflatoxigenic species, is used in the fermentation and chemical industries to produce commercial products like itaconic acid and lovastatin (Barrios-González et al., 2020).

Global Standards for Aflatoxin Limits in Food Products

Various countries and international organizations have established regulatory limits for aflatoxins in food and beverages to ensure consumer safety. The permissible levels typically range between 4 to 20 parts per billion (ppb), with the Codex Alimentarius Committee recommending a threshold of 10 ppb.

Key Regulatory Limits:

- FDA (U.S.A.):

- 20 ppb for all feed products (Dohlman, 2003).

- 15 ppb for raw peanuts, 20 ppb for human food, and 20 ppb for animal feed (FDA, 2020).

- WHO Guidelines:

- 0 ppb for children’s food, 20 ppb for adult food, and 55 ppb for animal feed. (Joint FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission, 1995).

- Codex Alimentarius Standards:

- 15 µg/kg for tree nuts (for further processing) and 10 µg/kg for ready-to-eat nuts.

- 15 µg/kg in peanuts, 0.5 µg/kg in milk and fruit juices (FAO/WHO, 1995).

- Australia & New Zealand:

- Maximum 15 µg/kg in nuts and nut products, and 5 µg/kg in all other foods (Australia New Zealand Food Authority, 1999).

- EU & UK Regulations:

- Total aflatoxins (B1+B2+G1+G2) must not exceed 4 µg/kg in cereals, peanuts, nuts, and dried fruits for human consumption.

- Aflatoxin B1 alone must remain below 2 µg/kg (EC No 1881/2006).

- India (FSSAI):

- 15 µg/kg in cereals, pulses, and nuts for processing; 10 µg/kg in ready-to-eat nuts; 30 µg/kg in spices.

- Aflatoxin M1 in milk capped at 0.5 µg/kg (FSSAI, 2020).

These regulations reflect a global effort to minimize aflatoxin exposure, balancing food safety with agricultural and trade considerations.

Cutting-edge approaches to manage aflatoxin contamination.

Cold Plasma (CP): CP has shown significant potential in this regard, as it generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that efficiently break down aflatoxins on food surfaces without compromising the food’s nutritional quality or safety. Research has demonstrated that exposing food to cold atmospheric pressure plasma for just eight minutes can reduce aflatoxin levels by 93% (Hojnik et al., 2019; Apalangya et al., 2024). CP is particularly effective against the most toxic form of aflatoxin, B1, making it significantly less harmful. Several studies have also confirmed its ability to inhibit the activity of aflatoxin-producing fungi, such as Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Moreover, this technology aids in breaking down various types of aflatoxins (B1, B2, G1, and G2) commonly found in food products like cereals and nuts (e.g., groundnuts). Due to its high efficacy, low operational cost, and minimal impact on the food’s nutritional value, cold plasma offers a sustainable and promising solution for controlling aflatoxin contamination (Apalangya et al., 2024).

Irradiation: A number of studies explored gamma-ray (γ-ray) irradiation as a potential method for reducing aflatoxin levels. Aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2 solutions were exposed to cobalt-60 irradiation at doses of 1, 2, 4, and 8 kGy. The results showed a significant reduction in aflatoxin levels, particularly for the highly toxic B1 and G1 variants, highlighting γ-irradiation as a promising decontamination method (Bozinou et al., 2024). Additionally, research suggests that combining UV light with hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) effectively detoxifies aflatoxin-contaminated food faster than other methods. UV treatment is particularly advantageous due to its affordability, minimal impact on food quality, and ability to break down aflatoxin B1 into aflatoxin B2a, a compound over 200 times less toxic. However, its limited penetration and “shadow effect” pose challenges when applied to solid materials. H₂O₂, on the other hand, oxidizes aflatoxins into less toxic compounds without leaving harmful residues or significantly altering food quality. To enhance its effectiveness, H₂O₂ is often combined with heat, radiation, or alkali (Shen et al., 2021).

Gamma irradiation has proven highly effective in reducing aflatoxins in food. In naturally contaminated corn kernels, it reduces aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) levels by 69.8% to 94.5% when exposed to 1–10 kGy doses. In soybeans, AFB1 reduction occurs at doses above 10 kGy, with over 95% degradation achieved through combined irradiation treatments (Serra et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Mahmoud et al., 2025). These findings highlight gamma irradiation as a powerful method for significantly lowering aflatoxin contamination in various food products.

High Pressure Processing (HPP): HPP is an emerging non-thermal technology that enhances food safety by inactivating spoilage microorganisms and extending shelf life without altering the food’s organoleptic properties. It damages microbial membranes, disrupts nutrient uptake and waste disposal, and causes protein denaturation and enzyme inactivation. HPP’s effectiveness varies across microbial species and strains, making it a versatile and widely used method for preserving agricultural and food products (Huang et al., 2014). For example, High-pressure ammoniation has proven to be a highly effective method for detoxifying aflatoxin-contaminated grain. In a study where Aspergillus parasiticus was used to contaminate yellow corn with 4000 μg/kg of total aflatoxin, two ammoniation procedures were tested: atmospheric pressure at ambient temperature (AP/AT) for 24 hours and high pressure at 2 bar and 121°C (HP/HT) for 15 minutes. Results showed that the HP/HT procedure achieved significantly higher aflatoxin reduction compared to AP/AT. Using HPLC with fluorescence detection, the study confirmed that high-pressure ammoniation more effectively degraded aflatoxins, making it a superior and commercially viable technique for reducing aflatoxin contamination in grains (Gomaa et al., 1997). Pallarés et al. (2022) reported that HPP (600 MPa for 5 minutes) effectively reduced emerging mycotoxins in juice and milk models, achieving reduction rates between 11% and 75.4%. This was significantly higher compared to traditional thermal treatment (HT), highlighting HPP’s superior efficacy in mycotoxin reduction.

Conclusion.

Cold plasma, HPP, gamma irradiation, and UV-H₂O₂ treatments are all effective methods for reducing mycotoxin contamination in food. Cold plasma, in particular, is a promising, non-thermal technology that offers a sustainable approach to decontamination without compromising food safety. These advanced methods have proven to be more efficient than traditional treatments, making them valuable tools for enhancing food safety and extending shelf life. Given their effectiveness, these technologies present promising solutions for mitigating mycotoxin risks in agriculture, improving food security, and protecting public health in the future. Understanding these evolutionary patterns and genetic mechanisms is crucial for developing strategies to mitigate the risks posed by these toxins, which contaminate a significant portion of global food supplies and threaten both human and animal health (Sharma et al., 2025).

Leave a comment