Post-harvest losses of fruits and vegetables are high due to their perishable nature. Their soft epicarp/exocarp makes them highly susceptible to mechanical damage and microbial spoilage, leading to significant losses. Typically, the shelf life of most fruits is about a week, with some, like berries, lasting only 2–3 days under normal or uncontrolled storage conditions. Edible coatings, on the other hand, can extend the shelf life of fruits during post-harvest handling, transportation, storage, and selling (Yadav et al., 2022). Moreover, improper handling during harvesting, transportation, and storage can render the fruits unsuitable for consumption due to damage, which may ultimately affect their shelf life, organoleptic properties, and marketability, resulting in substantial economic losses and exacerbating the issue of food waste.

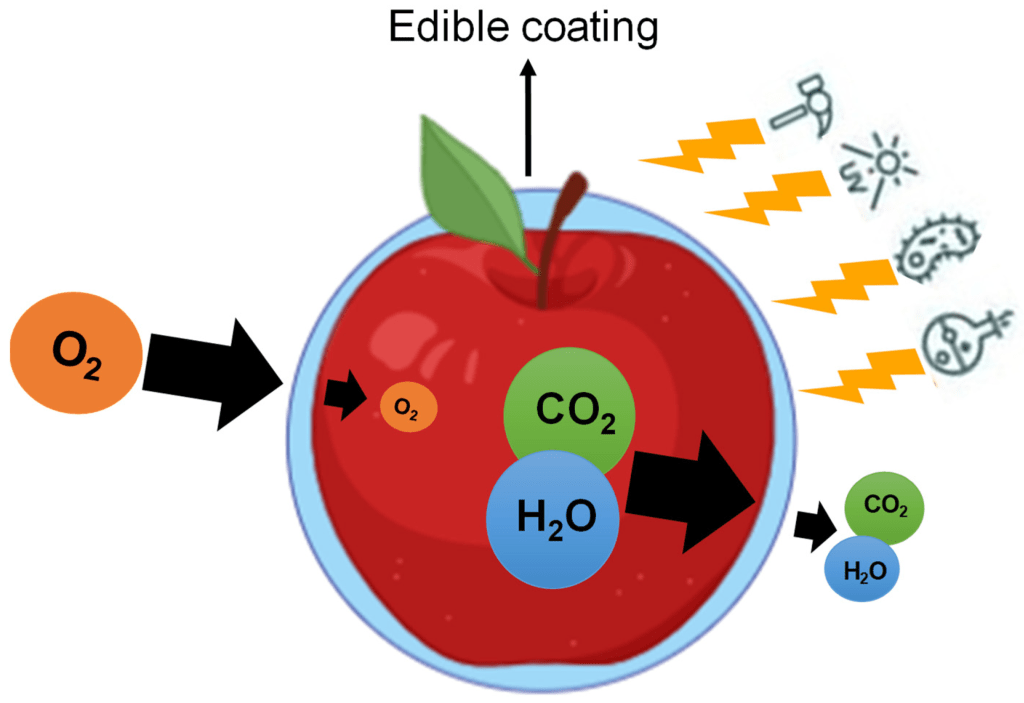

Figure 1: Key Functions of Edible Coatings on Fresh Produce (Source: de Oliveira Filho et al., 2021).

To address this issue, the use of edible coatings (Table 1) in the agro-food industry can help mitigate rapid post-harvest spoilage in fruits and vegetables. These coatings have the potential to improve the shelf life of fresh produce, as they act as effective barrier agents by forming a semipermeable protective layer between the fruit’s surface and the surrounding environment (oxygen and carbon dioxide), as illustrated in Figure 1. In fact, coatings on fresh produce can lower the respiration rate and ethylene biosynthesis, ultimately delaying the fruit’s ripening and biochemical changes. Additionally, the structural integrity of various alginic acid salts, such as sodium alginate, calcium alginate, magnesium alginate, and potassium alginate, protects fruits from mechanical, physical, biochemical, and biological influences during post-harvest handling, transportation, and storage. This minimises quality loss and improves the marketability of the fruits (García et al., 2016; Vieira et al., 2021).

In recent years, the use of biodegradable edible coatings (BECs) combined with electrostatic spraying techniques has proven to be an effective, economical, and environmentally friendly method for prolonging the shelf life of perishable fruits and vegetables (Maftoonazad and Ramaswamy, 2019).

Electrostatic spray coatings on Fresh Produce

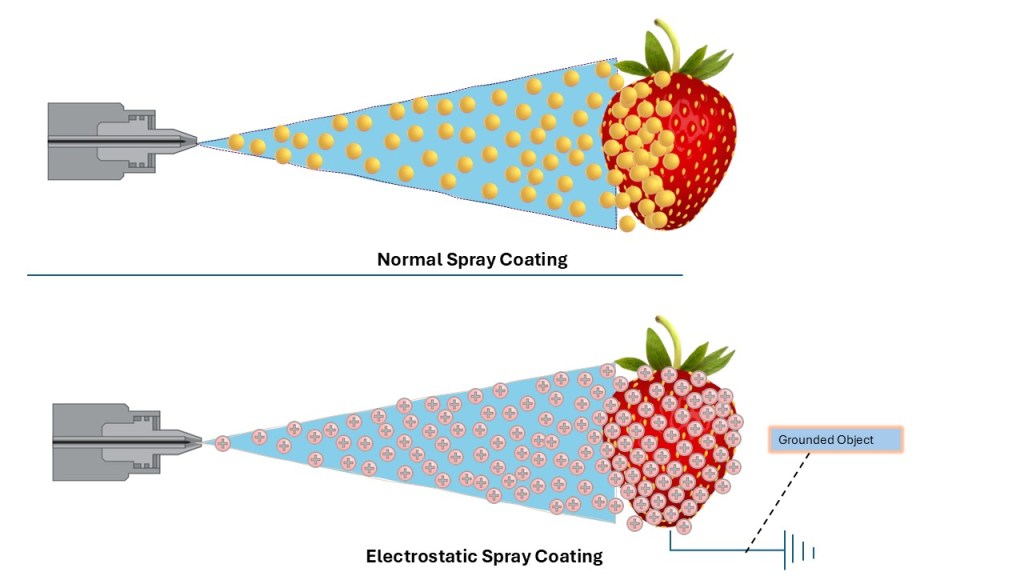

Electrostatic coating (EC) is an emerging technology in the food and agricultural industries for applying edible coatings to fruits and vegetables. This method offers a simple, rapid, and efficient application process, ensuring uniform distribution and durable, smooth coatings on produce surfaces (Deveau, 2018). EC is versatile, compatible with both powdered and liquid coatings, and effectively preserves the quality of fresh and processed foods, including appearance, shelf life, taste, flavor, and aroma. Its applications extend across multiple food sectors, such as confectionery, bakery, cheese, and meat processing (Barringer and Sumonsiri, 2015). The difference between normal and electrostatic spray coating is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Comparison of Uniformity Between Normal and Electrostatic Spray Coating.

In fact, the EC operates on the principle of “opposite attraction.” First, an edible coating solution is prepared and combined with high-pressure air before passing through a revolving spray nozzle. Inside the nozzle, droplets are atomised and pass through an electrode, which induces either a positive or negative charge, depending on the polarity of the DC power supply, onto the droplets. These charged droplets are then carried by air streams, following electrical field lines toward the oppositely charged surface of the fruit. The charged droplets, either negatively or positively charged depending on the polarity, are carried by air streams along the electrical field lines towards the fruit, maintaining their charge.

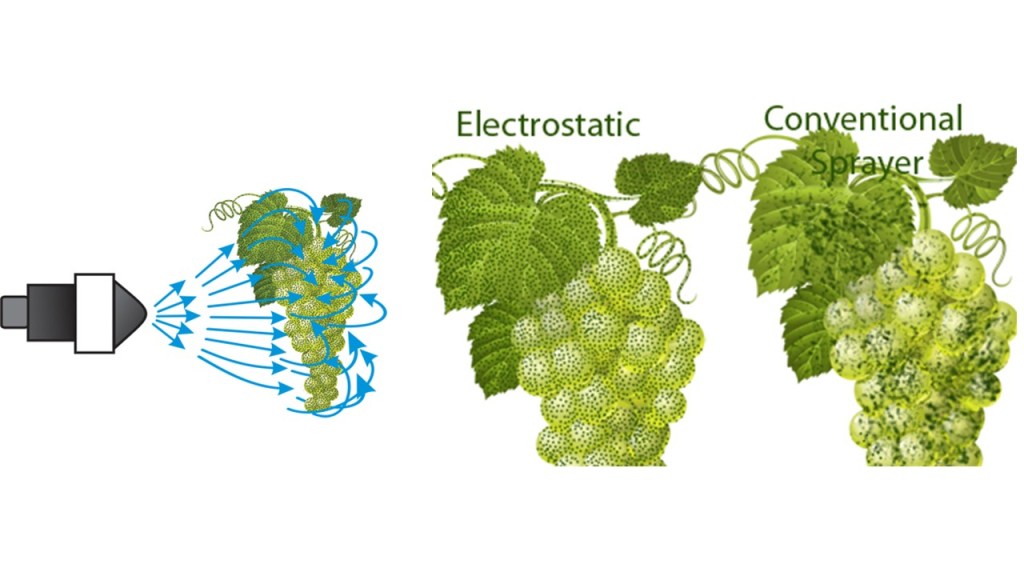

Figure 3: A schematic diagram of electrostatic spraying machine used for fruits coating (Adapted from Tathastu, 2022).

The electrostatic force of attraction, approximately 60 times stronger than gravity, allows the droplets to move upwards against gravity, coating the fruit and covering all surfaces, including hidden areas, within a minute (Barringer and Sumonsiri, 2015; Ghaster, 2016; Tathastu, 2022). The average diameter of droplets produced by electrostatic spraying is around 50 µm, depending on factors such as the charging voltage, nozzle properties, airflow speed, liquid flow rate, and the distance between the nozzle tip and electrode (Deveau, 2018; Tathastu, 2022). Due to the strong electrostatic forces, the droplets adhere uniformly, even reaching hidden or curved surfaces (Figure 3). In advanced applications, edible coatings can also be applied using layer-by-layer electrostatic deposition, where oppositely charged biopolymers (such as positively charged chitosan and negatively charged alginate or pectin) are alternately deposited to form multilayer coatings. This approach allows precise control over coating properties and has been shown to enhance microbial stability, reduce moisture loss, and significantly extend shelf-life without additional active agents (Arnon et al., 2015).

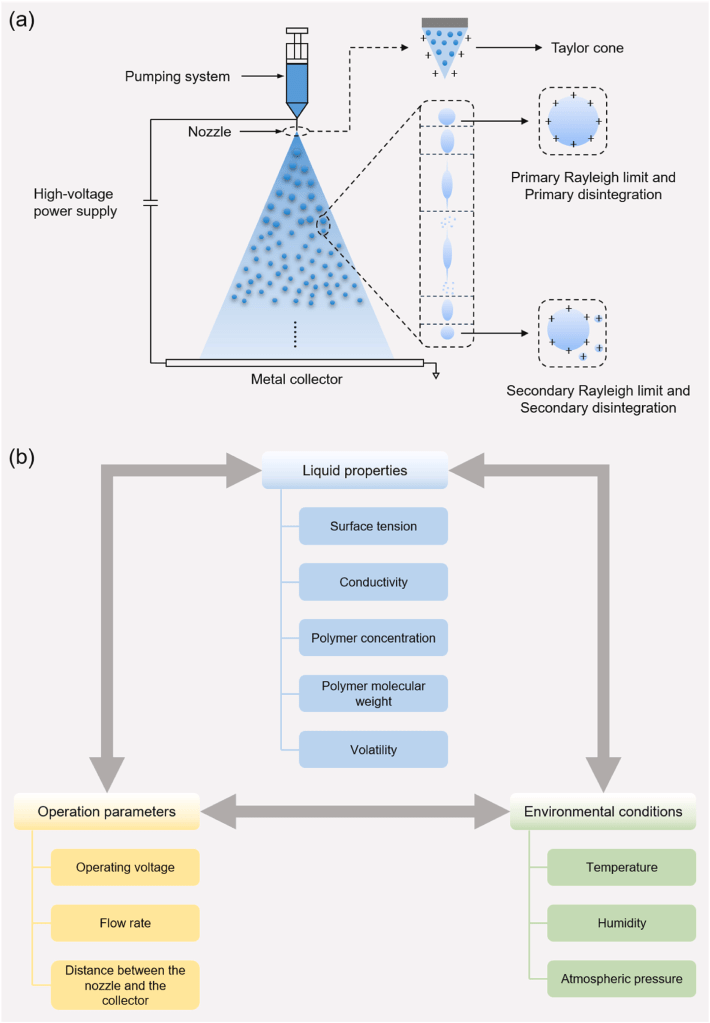

Electrostatic spraying (ES) uses electrostatic forces to atomise liquid into fine droplets. A typical ES device includes a pump, nozzle, high-voltage power supply, and grounded collector (Figure 4a). Liquid is fed through a capillary where it forms a charged droplet that develops into a Taylor cone. A high-charge-density jet emerges, breaking into smaller droplets as it nears the Rayleigh limit. This disintegration process repeats as the droplets lose charge and mass (Gui et al., 2023).

Figure 4 (a) Schematic representation of electrospinning technology; (b) Key factors influencing the electrospinning process (Source: Gui et al., 2023).

The ES effect is influenced by operational parameters (voltage, flow rate, nozzle–collector distance), liquid properties (surface tension, conductivity, polymer traits), and environmental factors (temperature, humidity, pressure) (Figure 4b).

Furthermore, electrostatic spray coating offers better uniformity than traditional spraying methods, providing uniform surface coverage with a consistent film thickness of 50±5 μm, as opposed to normal spraying, which results in uneven distribution (40-60% coverage) and varying thickness (20-100 μm) due to gravity and droplet coalescence. In this system, a liquid is dispersed into droplets ranging from 0.1 to 1,000 μm, with the droplets forming due to electrostatic forces charging the liquid surface (Barringer and Sumonsiri, 2015). EC offers several advantages, including cost-effectiveness due to material, time, and labor savings. It provides a uniform deposit on target surfaces with even-sized, high-quality droplets, thereby extending the shelf life of foods (Tathastu, 2022). The advantage of electrostatic coating is its ability to produce fine droplets with minimal energy, preventing coalescence due to the droplets’ same charge polarity. The coating’s effectiveness improves as powder particle size decreases, cohesiveness and resistivity increase, and targets have higher water activity, lower resistivity, and shorter charge decay times. These factors influence the transfer efficiency, adhesion, dust, evenness, and functionality of the coating, which are essential for predicting coating performance in food production and selecting the best system for coating food products.

Peretto et al. (2017) reported that alginate-based coatings applied via ES significantly prolonged the shelf life of strawberries compared to non-electrostatic spraying (NES). For instance, visual decay was absent in ES-coated strawberries up to 10 days, whereas NES-coated fruits showed about 3% decay. Similarly, color parameters (L, a, b) were 25.18, 27.44, and 15.41 for ES-coated fruits, compared to 27.10, 25.34, and 13.71 for NES-coated fruits. The firmness of ES-coated fruits was also higher, around 2.5 N, compared to 2 N for NES-coated fruits.

Electrostatic spraying on fresh fruits and vegetables not only ensures food safety but also significantly reduces the public health burden associated with fresh produce. For example, Ganesh et al. (2012) demonstrated that electrostatic spraying of a combined malic acid and lactic acid solution (3% each) on spinach and iceberg lettuce inhibited Escherichia coli by 4.0 and 2.5 log CFU/g, respectively, compared to 5.9 log CFU/g in the control during 15 days of storage at 4°C. Jiang et al. (2020) used electrostatic coating technology with chitosan and evaluated the shelf-life parameters over 15 days of storage at 4°C. They found that coatings with 61 kilodaltons (kDa) were the most effective, with weight loss, firmness loss, decrease in flavonoids, and mold growth measuring 5.28%, 17.97%, 18.24%, and 5.8 log CFU, respectively, for coated samples, compared to 6.5%, 49.47%, 40.18%, and 6.65 log CFU for uncoated strawberries. Similarly, Jiang et al. (2019) found that chitosan-based edible coatings applied via electrostatic spraying formed a continuous, smooth, and uniform protective layer, in contrast to conventional spraying (CS). ES chitosan coatings extended the shelf-life of strawberries by at least 2 days compared to CS. With an 88.1% deacetylation degree, ES chitosan coatings show great potential for industrial applications in fresh produce, offering a safe, economical, and efficient technique (Jiang et al., 2019).

Common biopolymers used in food and agricultural applications originate from plant, animal, and microbial sources (Table 1). Among these, plant-derived biopolymers are generally preferred due to their cost-effectiveness, widespread availability, and compatibility with vegetarian and vegan dietary practices. The most commercially prevalent bio-based edible coatings include lipid-based formulations, polysaccharides, plant-derived gums, and resins (Guimaraes et al., 2018).

Table 1: Classification of Edible Coatings for Food Preservation.

| Category | Type | Examples | Key Properties | Common Applications |

| Polysaccharide-Based | Cellulose derivatives | Methylcellulose, HPMC, Carboxymethylcellulose | Water-soluble, moderate barrier to O₂/CO₂ | Fruits (apples, pears), baked goods |

| Chitosan | Crab/fungal-derived chitosan | Antimicrobial, biodegradable, enhances shelf life | Berries, seafood, meat products | |

| Starch | Corn, potato, tapioca starch | Low cost, good film-forming but hydrophilic | Fresh-cut vegetables, nuts | |

| Alginate | Sodium alginate (from seaweed) | High moisture retention, forms gels with Ca²⁺ | Citrus fruits, meat coatings | |

| Protein-Based | Animal proteins | Whey, casein, gelatin, collagen | Excellent O₂ barrier, elastic but water-sensitive | Cheese, sausages, processed meats |

| Plant proteins | Soy protein, corn zein, wheat gluten | Heat-stable, moderate moisture barrier | Cereals, snacks, fried foods | |

| Lipid-Based | Waxes | Carnauba wax, beeswax, candelilla wax | Superior water barrier, glossy finish | Citrus fruits, cucumbers, avocados |

| Fatty acids | Stearic acid, oleic acid | Hydrophobic, reduces water loss | Nuts, dried fruits | |

| Composite | Polysaccharide-Lipid | Chitosan-beeswax, starch-palmitic acid | Combines gas barrier (polysaccharide) + moisture resistance (lipid) | Fresh-cut produce, ready-to-eat meals |

| Protein-Polysaccharide | Whey-alginate, gelatin-pectin | Enhanced mechanical strength and functionality | Meat, fish, delicate fruits | |

| Active Coatings | Antimicrobial | Chitosan + thyme oil, silver nanoparticles | Inhibits mould/bacterial growth (e.g., Botrytis, E. coli) | Perishable fruits, poultry |

| Antioxidant | Vitamin E, tocopherols, polyphenol-infused | Delays oxidative rancidity and browning | Nuts, sliced fruits, processed meats | |

| Smart Coatings | pH-responsive | Anthocyanin-based colour indicators | Visual spoilage detection (colour change at specific pH) | Packaged seafood, dairy |

| Temperature-sensitive | Thermo-releasing antimicrobials (e.g., encapsulated citral) | Releases active compounds at target temperatures | Ready-to-eat meals |

Source: (Han, 2005; Embuscado and Huber, 2009; Dhall, 2013; Ahiduzzaman, 2022).

In conclusion, EC technology offers a highly effective, cost-efficient, and environmentally friendly solution for extending the shelf-life of perishable fruits and vegetables. By creating uniform coatings that reduce respiration, water loss, and microbial growth, EC significantly improves food safety and quality. Studies demonstrate that electrostatic spraying enhances the preservation of fruits like strawberries, apple, citrus reducing spoilage, maintaining firmness, glossiness, and minimising spoilage. With its potential to apply both liquid and powder coatings seamlessly, EC is an innovative method that can benefit the agricultural and food industries by reducing post-harvest losses and ensuring safer, longer-lasting produce.

References:

Ahiduzzaman, M. ed. (2022). Postharvest Technology: Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Applications. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.101283

Arnon, H., Granit, R., Porat, R. and Poverenov, E. (2015). Development of polysaccharides-based edible coatings for citrus fruits: A layer-by-layer approach. Food chemistry, 166, pp.465-472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.061

Barringer, S.A. and Sumonsiri, N. (2015). Electrostatic coating technologies for food processing. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 6(1), pp.157-169. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-022814-015526

de Oliveira Filho, J.G., Miranda, M., Ferreira, M.D. and Plotto, A. (2021). Nanoemulsions as edible coatings: A potential strategy for fresh fruits and vegetables preservation. Foods, 10(10), p.2438. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10102438

Deveau, J. (2018). Electrostatic Spraying in Agriculture. Available from: https://sprayers101.com/electrostatic/ (Accessed 27 March 2025).

Dhall, R.K. (2013). Advances in edible coatings for fresh fruits and vegetables: a review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 53(5), pp.435-450. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2010.541568

Embuscado, M.E. and Huber, K.C. (2009). Edible films and coatings for food applications (Vol. 9, pp. 169-208). New York, NY, USA:: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-92824-1

Ganesh, V., Hettiarachchy, N.S., Griffis, C.L., Martin, E.M. and Ricke, S.C. (2012). Electrostatic spraying of food‐grade organic and inorganic acids and plant extracts to decontaminate Escherichia coli O157: H7 on spinach and iceberg lettuce. Journal of Food Science, 77(7), M391-M396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02719.x

García, M.P.M., Gómez-Guillén, M.C., López-Caballero, M.E. and Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. (2016). Edible films and coatings: fundamentals and applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, pp 585-587. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315373713

Ghaster, K. (2016). What Electrostatic Painting is and Why it Works so Well? Available From: https://www.ghasterpaintinginc.com/blog/what-electrostatic-painting-is-and-why-it-works-so-well/ (Accessed 27 March 2025).

Gui, X., Shang, B. and Yu, Y. (2023). Applications of electrostatic spray technology in food preservation. LWT, 190, p.115568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115568

Guimaraes, A., Abrunhosa, L., Pastrana, L.M. and Cerqueira, M.A. (2018). Edible films and coatings as carriers of living microorganisms: A new strategy towards biopreservation and healthier foods. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 17, 594-614. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12345

Han, J.H. ed. (2005). Innovations in food packaging. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2011-0-06876-X

Jiang, Y., Yu, L., Hu, Y., Zhu, Z., Zhuang, C., Zhao, Y. and Zhong, Y. (2019). Electrostatic spraying of chitosan coating with different deacetylation degree for strawberry preservation. International journal of biological macromolecules, 139, 1232-1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.113

Jiang, Y., Yu, L., Hu, Y., Zhu, Z., Zhuang, C., Zhao, Y. and Zhong, Y. (2020). The preservation performance of chitosan coating with different molecular weight on strawberry using electrostatic spraying technique. International journal of biological macromolecules, 151, 278-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.169

Maftoonazad, N. and Ramaswamy, H.S. (2019). Application and evaluation of a pectin-based edible coating process for quality change kinetics and shelf-life extension of lime fruit (Citrus aurantifolium). Coatings, 9, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings9050285

Peretto, G., Du, W.X., Avena-Bustillos, R.J., Berrios, D.J., Sambo, P. and McHugh, T.H. (2017). Electrostatic and conventional spraying of alginate-based edible coating with natural antimicrobials for preserving fresh strawberry quality. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 10(1), 165-174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-016-1808-9

Tathastu (2022). Electrostatic Agriculture Backpack Sprayer. Available from: https://tathastuservices.com/ele_agriculture_sprayer_backpack_model.html (Accessed 27 March 2025).

Vieira, T.M., Moldão-Martins, M. and Alves, V.D. (2021). Composite coatings of chitosan and alginate emulsions with olive oil to enhance postharvest quality and shelf life of fresh figs (Ficus carica L. cv.‘Pingo De Mel’). Foods, 10(4), p.718. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040718

Yadav, A., Kumar, N., Upadhyay, A., Sethi, S. and Singh, A. (2022). Edible coating as postharvest management strategy for shelf‐life extension of fresh tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.): An overview. Journal of Food Science, 1-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.16145

Leave a comment