Introduction

Post-harvest losses of fruits are very high, as fruits are highly perishable due to their soft epicarp/exocarp, making them highly susceptible to mechanical damage and post-harvest microbial spoilage, resulting in significant losses. Normally, the shelf life of most fruits is about a week; for some, such as berries, it can be even shorter, just 2–3 days under normal or uncontrolled storage conditions. However, this shelf life can be extended by using edible coatings, which help prolong freshness during post-harvest handling, transportation, and storage (Kumar et al., 2018; Yadav et al., 2022). If fruits are not properly handled during transportation and storage, they may become unsuitable for consumption and marketability, leading to huge economic losses (Romero, 2019). In recent years, the application of biodegradable edible coatings (BECs) incorporated with essential oils, applied using electrostatic spraying techniques on fruit surfaces has emerged as an effective, economical, and environmentally friendly method for extending the shelf life of perishable fruits and vegetables (Maftoonazad and Ramaswamy, 2019).

BECs act as excellent barrier agents by creating a semipermeable protective layer between the fruit surface and the surrounding environment (oxygen and carbon dioxide), thereby helping to lower the respiration rate and ethylene biosynthesis, ultimately delaying fruit ripening and associated biochemical changes. Similarly, the structural integrity of various forms of alginic acid salts, such as sodium alginate, calcium alginate, magnesium alginate, and potassium alginate, protects fruits against mechanical, physical, biochemical, and biological influences during post-harvest handling, transportation, and storage. This minimises quality loss and enhances the marketability of fruits (García et al., 2016; Tokatlı and Demirdöven, 2020; Vieira et al., 2021).

However, the main objective of this study is to explore the use of potassium alginate as a substitute for sodium alginate in edible coatings. Both sodium and potassium belong to the same group in the periodic table (alkali metals) and possess similar chemical characteristics. At the same time, there is growing awareness of the need to reduce excessive sodium intake in human diets, while potassium, an essential mineral, plays a critical role in regulating vital bodily functions. Furthermore, potassium alginate, when combined with essential oils, holds great potential for enhancing the shelf life of fresh produce and could represent an innovative and eco-friendly solution for the food packaging industry.

Kay Factors to consider before using BECs on fruits and vegetables.

BECs, when applied directly to food surfaces, help mitigate environmental stressors (Eyiz et al., 2020). To be effective, these coatings must meet several essential criteria: they must be edible, biodegradable, environmentally sustainable, compatible with probiotics, and compliant with national food and environmental regulations (Chen et al., 2020; Abdel-Naeem et al., 2021).

An ideal EC should serve multiple protective functions, including:

- Acting as an effective barrier against gas and moisture exchange

- Slowing fruit ripening and aging processes

- Maintaining fruit appearance and shine

- Providing mechanical stability

- Preventing damage from pests and pathogens (Iñiguez-Moreno et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2022).

Additionally, high-quality BECs should effectively carry and sustain probiotic activity over extended periods (Marín et al., 2019). For example, Pereira et al. (2016) demonstrated that incorporating lactic acid bacteria (LAB) into whey protein-based edible films not only improved the films’ durability and strength but also maintained high LAB viability for 60 days under refrigeration.

On top of that, one of the most important attributes of BECs is their ability to adhere uniformly to the surface of fruits, ensuring they function efficiently and effectively. In fact, the effectiveness, flexibility, adhesion, stability, and extensibility of BECs primarily depend on the presence of compounds such as emulsifiers, plasticisers, and functional compounds such as texture enhancers, antioxidants, antimicrobials, and nutraceuticals (Pereira et al., 2016; Pedreiro et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2022). In fact, the quality of BECs is influenced not only by factors such as viscosity, pH, coating thickness, but also by the degree of polymer cross-linking (Iñiguez-Moreno et al., 2021). Generally, the outer skin (pericarp) of fruits or vegetables has a soft texture, making it highly susceptible to mechanical damage, especially during harvesting and all stages of postharvest handling. Meanwhile, injuries in fruits accelerate respiration rates, moisture loss, and ethylene biosynthesis, while also increasing spoilage, ultimately reducing shelf-life and fruit quality. Therefore, an effective BEC should have the ability to resist mechanical shocks and abrasion to help maintain the structural integrity of the fruit. Additionally, the coating material should not negatively affect the texture, taste, or sensory properties of the fruit, such as in the case of plums, and berries. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between fruit physiology, biochemical composition, and edible coating properties is essential before selecting BECs (Saha et al., 2017; Strano et al., 2017; Yadav et al., 2022).

Attributes Alginate-based edible coatings and their properties.

Alginate films and coatings are biodegradable, biocompatible, and non-toxic film-forming bio-macromolecules that improve the quality attributes of processed foods and fresh produce by reducing oxidative rancidity, oil absorption, shrinkage, moisture loss, and preserving flavor and color (Nair et al., 2020; Chaudhary et al., 2020). It is a linear anionic copolymer naturally extracted from seaweed (Phaeophyceae). Alginate consists of biopolymeric α-L-Guluronic acid (G) and β-D-Mannuronic acid (M) polymers and possesses several properties, making it commonly used in various industries including scaffolding, welding rod production, dental applications, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, agriculture, and food industries, therefore gaining increasing attention in daily life. It has been reported that the biocompatibility of M monomers is 10 times more immunogenic and more effective for promoting cytokine synthesis compared to G monomers (Axpe and Oyen, 2016; Reddy, 2021). Due to its excellent film-forming and gelling properties, it forms uniform, water-soluble, and transparent films, while also having lower permeability to fats, oils, and oxygen, which helps retard lipid oxidation in various fruits and vegetables (Xu et al., 2020; Pereira and Cotas, 2020; Nair et al., 2020).

Properties of Alginic Acid and Its Salts

Alginic acid exists in various forms, including its salts such as sodium, magnesium, potassium, calcium, and ammonium salts. Monovalent cation salts (e.g., sodium alginate, potassium alginate, and ammonium alginate) are soluble in both cold and hot water, whereas divalent cation salts (e.g., magnesium alginate and calcium alginate) are water-insoluble (McHugh, 2003; Parreidt et al., 2018). This difference arises from the presence of carboxylic (–COO⁻) groups in the alginate structure, which carry a negative charge and exhibit high affinity for divalent cations, forming strong, water-insoluble bonds. Consequently, divalent alginates possess remarkable water absorption capacity, capable of absorbing 200–300 times their original weight (Reddy, 2021).

pH-Dependent Solubility and Viscosity of Alginate

Alginate exhibits very low solubility at acidic pH levels due to the deprotonation of carboxylic groups (–COO⁻) in its structure. Studies indicate that alginate viscosity remains stable above pH 5 but decreases significantly below this threshold. This reduction occurs because protonation converts –COO⁻ groups into –COOH, promoting hydrogen bond formation between polymer chains in aqueous solutions, thereby lowering viscosity. Conversely, under highly alkaline conditions (pH > 11), alginate undergoes depolymerisation, leading to a notable decline in viscosity (Liu et al., 2002; Mahmoodi, 2013; Wang et al., 2017; Reddy, 2021).

Mucoadhesive Properties of Alginate

Alginate exhibits superior mucoadhesive strength compared to other polymers (e.g., chitosan, polystyrene, lactic acid, and carboxymethyl cellulose) due to the presence of anionic carboxylic groups (–COO⁻) in its structure, which enhance binding to mucosal layers. Polyanionic polymers like alginate generally demonstrate stronger bioadhesion than non-ionic or polycationic polymers. Consequently, alginate is widely utilised as an effective mucosal drug delivery vehicle, particularly for targeted drug release in the gastrointestinal tract and nasopharynx (Bernkop-Schnürch et al., 2001; Szekalska et al., 2017; Putri et al., 2021).

Sodium Alginate: Properties and Applications

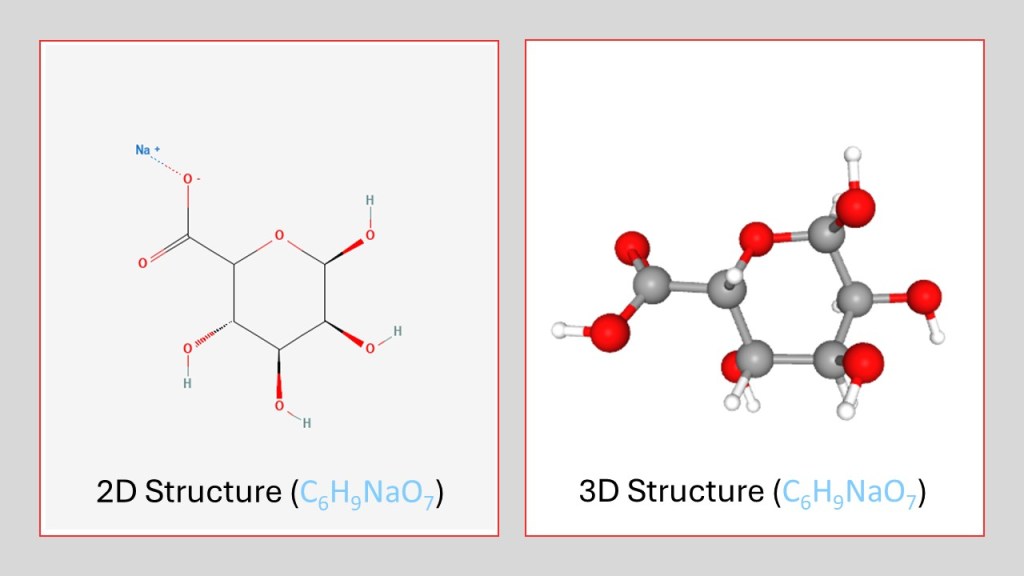

Figure 2: 2D and 3D structure of sodium alginate (Image Source: NCBI, 2022).

Sodium alginate (SA) is the sodium salt of alginic acid, containing between 30-60% alginic acid. It is a polysaccharide-based edible coating extracted from the cell wall of brown algae. SA is soluble in water and has been widely used in the food industry as a thickening, gelling, preservative, emulsifying, or stabilising agent, as well as a coating for fruits and vegetables (Puscaselu et al., 2020; Das et al., 2020). SA-based coatings can enhance the nutritional qualities of foods due to their mechanical, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties (Nair et al., 2020). Sodium alginate-based films exhibit strong tensile strength and good antioxidant activities due to their strong intermolecular and intramolecular cross-linking interactions (Ruan et al., 2019; Nair et al., 2020). As a result, it has been used as an excellent film-forming agent to coat fresh produce due to its gelling ability, non-toxicity, pH responsiveness, biodegradability, and biocompatibility (Reddy, 2021).

Its properties are almost identical to those of potassium alginate (PA) , and it can easily dissolve in both cold and warm water. However, both SA and PA acquire unique properties when mixed with divalent cations such as Ca²⁺, Sr²⁺, and Ba²⁺, which induce gelation that is insoluble in water. This occurs because the divalent cations bind with the G block (α-L-Guluronic acid). After gelation, a “egg-box” like structure forms, creating cross-linkages between the oxygen atoms of the G-block and the divalent cations. This structure helps maintain the structural integrity of the coatings, improves water absorption, and provides tensile strength (Moody et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020; Pandey et al., 2021).

While SA remains widely used in the food industry, PA offers distinct health advantages by replacing Na not only in diets but also in edible coatings that consumers ingest with fresh or cooked foods (Kimica, 2022). PA demonstrates higher Na⁺ adsorption capacity, promoting the excretion of excess Na that contributes to hypertension. Recent studies report that PA is rich in dietary fiber and effective in suppressing hypertension, thereby helping to lower blood pressure (Chen et al., 2010; Szekalska et al., 2016; Fujiwara et al., 2021).

Potassium Alginate

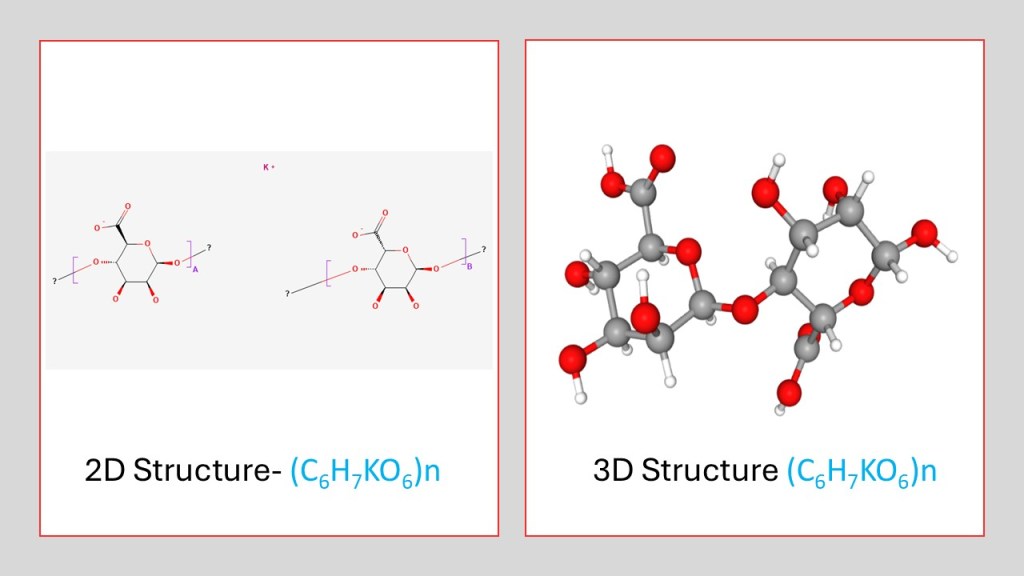

Potassium alginate, a polysaccharide-based edible coating, acts as an excellent barrier by forming a semipermeable protective layer between the fruit’s surface and the surrounding environment (Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide). This layer helps reduce the respiration rate and ethylene biosynthesis, ultimately delaying fruit ripening and biochemical changes. Similarly, the structural integrity of various alginic acid salts, including sodium alginate, calcium alginate, magnesium alginate, and potassium alginate, protects fruits from mechanical, physical, biochemical, and biological damage during post-harvest handling, transportation, and storage. As a result, these coatings minimise quality loss and improve fruit marketability (García et al., 2016; Tokatlı and Demirdöven, 2020; Vieira et al., 2021).

Figure 3: 2D and 3D structure of potassium alginate (Image Source: NCBI)

Applications and Benefits of Potassium Alginate

Potassium alginate, a salt derived from alginic acid (seaweed extract), serves as a versatile biopolymer with wide-ranging applications in agriculture, food, and pharmaceutical industries. It functions as an effective stabiliser, emulsifier, thickener, and gelling agent, offering a potential alternative to sodium alginate. Currently, the demand for potassium alginate in food and pharmaceutical sectors surpasses that of sodium alginate due to health concerns associated with excessive sodium intake (Kimica, 2022). For example, The National Health Service Act 2006 (UK) recommends a daily intake of 3.5g potassium and limits sodium to 2.4g for adults.

Beyond its technical uses, potassium alginate demonstrates significant health benefits:

- Metabolic Health: Reduces blood cholesterol and glucose levels

- Biocompatibility: Exhibits immunogenic properties suitable for pharmaceutical formulations

- Cardiovascular Protection: Mitigates risks of renal and cardiac hypertrophy (Szekalska et al., 2016; Kimica, 2022).

Regulatory Limits for Potassium Alginate (PA) in Food Products.

According to the FAO database, the maximum permitted levels of PA vary significantly across different food product categories. The regulatory limits are established as follows: reduced-fat creams, plain fermented milks, frozen fish, and infant weaning foods may contain up to 5000 mg/kg of PA, while plain buttermilk has a higher permitted limit of 6000 mg/kg. More restrictive limits apply to pasteurised cream (100 mg/kg) and sugars/syrups including maple syrup and brown sugar (300 mg/kg). For pasteurized canned products, the maximum permitted PA level is set at 2500 mg/kg (FAO, 2001). These carefully differentiated regulatory thresholds reflect the varying applications and safety considerations for potassium alginate across different food types.

Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on food additives.

Applications of Potassium Alginate in Different Fields

Potassium alginate (E 402) is a natural polymer that is nearly odourless and appears as a fibrous or granular powder, ranging in colour from white to yellow. It shares many properties with sodium alginate and is often used as a substitute in food applications. Over the past few decades, PA has found wide application in the pharmaceutical industry, food industry, agricultural sector, and medical field due to its unique properties, including gelling, thickening, emulsifying, stabilising, and binding capabilities, as well as its bioactivity, biocompatibility, demulcent effects, and immunomodulatory action (Zakharov et al., 2021; Reddy, 2021).

Potassium alginate in the food industry

PA is authorised as a safe food additive by the FAO, WHO, and under Directive 95/2/EC (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed, 2017a), and therefore holds significant value in the production of functional food products (Qin et al., 2018). For example, alginate has been used in a variety of food items, including fruit jams, jellies, instant noodles, ice cream toppings, food packaging, dairy products, and beer (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed, 2017a).

Shi et al. (2020) reported that the combined effect of using ultrasound at 15.6 W/cm² for 5 minutes with 0.4% potassium alginate marination on chicken breast meat resulted in average moisture loss, cooking loss, and shear force values of 1.29%, 16.53%, and 12.67 N, respectively. In contrast, the control treatment showed average values of approximately 3%, 24%, and 21 N, respectively. Similarly, the water-holding capacity of myofibrillar protein gel increased by 73.10% with potassium alginate marination compared to the control (66.44%). This improvement enhanced the textural properties, promoting good tenderness, preventing protein denaturation, avoiding off-flavors, and maintaining the appearance and eating quality traits of chicken (Shi et al., 2020). In another study evaluating the effect of PA (4 mg/mL) combined with ultrasound (300 W) on 300-day-old chicken breast meat, the treatment exhibited lower liquid loss, improved meat texture, and enhanced meat quality due to the dissociation of actomyosin in myofibrillar protein and reduced heat-denatured myosin protein. Thus, PA also shows great potential for improving chicken meat quality (Shi et al., 2021). According to the EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (2017b), potassium alginate (E 402) was listed as an ingredient on 41 food and beverage products, including food supplements, within the Mintel GNPD database during the 2011–2016 period. Margarines accounted for the majority of these products, indicating that this additive was most commonly used in this specific food category.

In terms of edible coatings, Chandran et al. (2020) applied a PA-based coating (Aloe gel + 1% PA) to tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruits over 36 days, and noted that the coated fruits exhibited firmness values of approximately 108 N, 54 N, 54 N, and 44 N at 0, 12, 24, and 36 days, respectively. Similarly, the sensory and textural attributes of the tomatoes, including glossiness, juiciness, texture, skin roughness, and skin tightness, remained superior up to 12 days of storage before gradually declining afterward. Additionally, there were only slight changes in total solids content during the storage period, with measurements of 88 mg/L, 87 mg/L, 83.86 mg/L, and 84 mg/L at 0, 12, 24, and 36 days, respectively. Notably, no diseases such as bacterial soft rot, Rhizopus, or Erwinia (major post-harvest pathogens) were observed in the coated fruits, unlike in the uncoated ones.

Potassium alginate in medical/ health field

Consumption of PA could offers greater health benefits than SA, as over Na intake can elevate the risk of hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. In contrast, PA decomposes in the GI tract, producing alginic acid and potassium ions. The released alginic acid then binds with Na present in the digestive system, forming SA and thereby helping eliminate excess hypertension-inducing Na from the body (Fujiwara et al., 2021).

For example, a study involving six hypertensive patients administered 45 g/day of alginic acid (containing 10% PA) for 5–9 weeks demonstrated that the treatment was well-tolerated, effectively managed electrolyte imbalances, and reduced gastrointestinal disturbances (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed, 2017b). Furthermore, Han et al. (2020) reported that potassium alginate oligosaccharides (PAO) can helps to reduce the risk of elevated systolic blood pressure (BP) and mean arterial pressure, thereby acting as an effective protective agent against heart failure. Additionally, PAO enhances microbial diversity in the digestive system by modulating gut microbiota (GM) composition. Specifically, it reduces the abundance of Phascolarctobacterium bacteria and Prevotella spp., suggesting a potential role in cardiovascular disease prevention.

PA has also been widely used in medical applications, particularly for treating heavily exuding wounds, bleeding wounds, chronic wounds, and hollow organ wounds (e.g., intestinal wounds). Alginate-based hydrogels, including bioactivated nanocellulose-alginate hydrogels, have shown significant therapeutic potential (Solanki & Solanki, 2012; Leppiniemi et al., 2017). For example, hydrogels prepared under neutral or weakly acidic conditions (pH 5.5–6.5) using calcium carbonate, carbonated water, and potassium alginate are highly suitable for wound healing dressings. These hydrogels are biocompatible, transparent (allowing wound monitoring), and quick to prepare in clinical settings. Additionally, they effectively absorb and retain wound exudates by taking up physiological saline during in vivo application, enhancing their therapeutic utility (Teshima et al., 2020; Zhang & Zhao, 2020).

Potassium Alginate in Animal Feed

PA is used in animal feed and has been proven to be both safe and nutritious. For instance, a one-year study on a potassium alginate-based supplement fed to dogs, cats, and fish found it to be safe, with no adverse effects observed in any of the animals. The study concluded that a dose of 40,000 mg of potassium alginate salts per kg of complete feed is safe for dogs, cats, salmonids, and other fish, and does not pose any risk to the aquatic ecosystem (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed, 2017a).

For more information: Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1533.

Conclusion and Future directions

Alginate is one of the most widely used polysaccharide-based seaweed products, valued for its broad range of applications across various sectors. Its desirable properties, such as gel-forming ability through crosslinking, biodegradability, biocompatibility, pH-responsiveness, and non-toxicity, make it especially useful in the food industry. In addition, alginates are economical, readily available, and compatible with dietary preferences such as vegetarianism and veganism, making them ideal for modern food practices.

Due to their ability to form stable structures when crosslinked with monovalent and divalent ions, alginates provide physical strength and resistance to both biotic and abiotic stress. This makes alginate-based coatings particularly effective for preserving fruits and vegetables post-harvest.

Despite these advantages, most research has historically focused on SA and calcium alginate, while PA remains relatively understudied. This represents a missed opportunity, especially considering its nutritional edge. PA offers similar functional benefits to SA but is healthier from a dietary standpoint. The recommended daily intake of sodium is 2.4 g, whereas potassium is 3.5 g. While sodium is abundant in processed foods, snacks, and beverages, potassium sources are more limited in the typical diet. Therefore, promoting the use of PA in food products, particularly in edible coatings, not only meets functional needs but may also contribute to improved nutritional balance by helping address potassium deficiencies.

Research Question:

Given its comparable functional properties and superior health profile, can potassium alginate serve as a better alternative to sodium alginate in food applications such as edible coatings—enhancing product quality while supporting healthier dietary intake of essential minerals?

References:

Abdel-Naeem, H.H., Zayed, N.E. and Mansour, H.A. (2021). Effect of chitosan and lauric arginate edible coating on bacteriological quality, deterioration criteria, and sensory attributes of frozen stored chicken meat. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 150, p.111928. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111928

Axpe, E. and Oyen, M.L. (2016). Applications of alginate-based bioinks in 3D bioprinting. International journal of molecular sciences, 17(12), p.1976. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17121976

Bernkop-Schnürch, A., Kast, C.E. and Richter, M.F. (2001). Improvement in the mucoadhesive properties of alginate by the covalent attachment of cysteine. Journal of controlled release, 71(3), 277-285. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-3659(01)00227-9

Cao, L., Lu, W., Mata, A., Nishinari, K. and Fang, Y. (2020). Egg-box model-based gelation of alginate and pectin: A review. Carbohydrate polymers, 242, p.116389. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116389

Chandran, T.T., Mini, C. and Anith, K.N. (2020). Quality evaluation of edible film coated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruits. Journal of Tropical Agriculture, 58(2), 219-227.

Chaudhary, S., Kumar, S., Kumar, V. and Sharma, R. (2020). Chitosan nanoemulsions as advanced edible coatings for fruits and vegetables: Composition, fabrication and developments in last decade. International journal of biological macromolecules, 152, 154-170. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.276

Chen, Y.Y., Ji, W., Du, J.R., Yu, D.K., He, Y., Yu, C.X., Li, D.S., Zhao, C.Y. and Qiao, K.Y. (2010). Preventive effects of low molecular mass potassium alginate extracted from brown algae on DOCA salt-induced hypertension in rats. Biomedicine and pharmacotherapy, 64(4), 291-295. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2009.09.004

Chen, F., Zhang, J., Chen, C., Kowaleguet, M.G., Ban, Z., Fei, L. and Xu, C. (2020). Chitosan-based layer-by-layer assembly: Towards application on quality maintenance of lemon fruits. Advances in Polymer Technology, 20, 1-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7320137

Das, S., Vishakha, K., Banerjee, S., Mondal, S. and Ganguli, A. (2020). Sodium alginate-based edible coating containing nanoemulsion of Citrus sinensis essential oil eradicates planktonic and sessile cells of food-borne pathogens and increased quality attributes of tomatoes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 162, 1770-1779. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.086

EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed, Rychen, G., Aquilina, G., Azimonti, G., Bampidis, V., Bastos, M.D.L., Bories, G., Chesson, A., Cocconcelli, P.S., Flachowsky, G. and Kolar, B. (2017a). Safety and efficacy of sodium and potassium alginate for pets, other non food‐producing animals and fish. EFSA Journal, 15(7), p.e04945. doi: https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4945

EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed, Younes, M., Aggett, P., Aguilar, F., Crebelli, R., Filipič, M., Frutos, M.J., Galtier, P., Gott, D., Gundert-Remy, U., Kuhnle, G.G., Lambré, C., Leblanc, J.C., Lillegaard, I.T., Moldeus, P., Mortensen, A., Oskarsson, A., Stankovic, I., Waalkens-Berendsen, I., Woutersen, R.A., Wright, M., Brimer, L., Lindtner, O., Mosesso, P., Christodoulidou, A., Horváth, Z., Lodi, F., Dusemund, B. (2017b). Re-evaluation of alginic acid and its sodium, potassium, ammonium and calcium salts (E 400-E 404) as food additives. EFSA Journal, 15(11), p.e05049. doi: https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.5049

Eyiz, V., Tontul, İ. and Türker, S. (2020). The effect of edible coatings on physical and chemical characteristics of fruit bars. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 14, 1775-1783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-020-00425-0

FAO (2001). Potassium alginate. Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/y0474s/y0474s5d.htm#bm193 (Accessed 02 July 2022).

Fujiwara, Y., Maeda, R., Takeshita, H. and Komohara, Y. (2021). Alginates as food ingredients absorb extra salt in sodium chloride-treated mice. Heliyon, 7(3), e06551. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06551

García, M.P.M., Gómez-Guillén, M.C., López-Caballero, M.E. and Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. (2016). Edible films and coatings: fundamentals and applications, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, pp 585-587. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315373713

Han, Z.L., Chen, M., Fu, X.D., Yang, M., Hrmova, M., Zhao, Y.H. and Mou, H.J. (2021). Potassium alginate oligosaccharides alter gut microbiota, and have potential to prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(18), p.9823. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22189823

Iñiguez-Moreno, M., Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A. and Calderón-Santoyo, M. (2021). An extensive review of natural polymers used as coatings for postharvest shelf-life extension: Trends and challenges. Polymers, 13, 1-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13193271

Kimica (2022). Potassium Alginate. Available from: https://www.kimica-algin.com/products/KaAlgin/ (Accessed 23 June 2022).

Leppiniemi, J., Lahtinen, P., Paajanen, A., Mahlberg, R., Metsä-Kortelainen, S., Pinomaa, T., Pajari, H., Vikholm-Lundin, I., Pursula, P. and Hytönen, V.P. (2017). 3D-printable bioactivated nanocellulose–alginate hydrogels. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 9(26), 21959-21970. doi: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b02756

Liu, X.D., Yu, W.Y., Zhang, Y., Xue, W.M., Yu, W.T., Xiong, Y., Ma, X.J., Chen, Y. and Yuan, Q. (2002). Characterization of structure and diffusion behaviour of Ca-alginate beads prepared with external or internal calcium sources. Journal of microencapsulation, 19(6), 775-782. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0265204021000022743

Maftoonazad, N. and Ramaswamy, H.S. (2019). Application and evaluation of a pectin-based edible coating process for quality change kinetics and shelf-life extension of lime fruit (Citrus aurantifolium). Coatings, 9, 1-14. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings9050285

Mahmoodi, N.M. (2013). Magnetic ferrite nanoparticle–alginate composite: Synthesis, characterization and binary system dye removal. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 44(2), 322-330. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2012.11.014

Marín, A., Plotto, A., Atarés, L. and Chiralt, A. (2019). Lactic acid bacteria incorporated into edible coatings to control fungal growth and maintain postharvest quality of grapes. Hortscience, 54, 337-343. doi: https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI13661-18

McHugh, D.J. (2003). A guide to the seaweed industry. Food and agriculture organization fisheries technical paper 441. Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/y4765e/y4765e08.htm#bm08 (Accesses: 23 June 2022)

Moody, C.T., Palvai, S. and Brudno, Y. (2020). Click cross-linking improves retention and targeting of refillable alginate depots. Acta biomaterialia, 112, 112-121. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2020.05.033

Nair, M.S., Tomar, M., Punia, S., Kukula-Koch, W. and Kumar, M. (2020). Enhancing the functionality of chitosan-and alginate-based active edible coatings/films for the preservation of fruits and vegetables: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 164, 304-320. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.083

Pandey, A.K., Sirohi, R., Gaur, V.K. and Pandey, A. (2021). Production and applications of pullulan. In Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals (pp. 165-221). Elsevier. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821888-4.00018-6

Parreidt, T.S., Müller, K. and Schmid, M. (2018). Alginate-based edible films and coatings for food packaging applications. Foods, 7(10), 1-38. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7100170

Pedreiro, S., Figueirinha, A., Silva, A.S. and Ramos, F. (2021). Bioactive Edible Films and Coatings Based in Gums and Starch: Phenolic Enrichment and Foods Application. Coatings, 11, p.1393. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11111393

Pereira, J.O., Soares, J., Sousa, S., Madureira, A.R., Gomes, A. and Pintado, M. (2016). Edible films as carrier for lactic acid bacteria. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 73, 543-550. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2016.06.060

Pereira, L. and Cotas, J. (2020). Introductory chapter: Alginates-A general overview. Alginates-recent uses of this natural polymer. IntechOpen, London. doi: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88381

Puscaselu, R.G., Lobiuc, A., Dimian, M. and Covasa, M. (2020). Alginate: From food industry to biomedical applications and management of metabolic disorders. Polymers, 12(10), 1-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12102417

Putri, A.P., Picchioni, F., Harjanto, S. and Chalid, M. (2021). Alginate modification and lectin-conjugation approach to synthesize the mucoadhesive matrix. Applied Sciences, 11(24), p.11818. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/app112411818

Qin, Y., Jiang, J., Zhao, L., Zhang, J. and Wang, F. (2018). Applications of alginate as a functional food ingredient. In Biopolymers for food design. Handbook of Food Bioengineering (pp. 409-429). Academic Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811449-0.00013-X

Reddy, S.G. (2021). ‘Alginates – A Seaweed Product: Its Properties and Applications’, in I. Deniz, E. Imamoglu, T. Keskin-Gundogdu (eds.), Properties and Applications of Alginates, IntechOpen, London. doi: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.98831

Ruan, C., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Sun, Y., Gao, X., Xiong, G. and Liang, J. (2019). Preparation and antioxidant activity of sodium alginate and carboxymethyl cellulose edible films with epigallocatechin gallate. International journal of biological macromolecules, 134, 1038-1044. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.143

Saha, A., Tyagi, S., Gupta, R.K. and Tyagi, Y.K. (2017). Natural gums of plant origin as edible coatings for food industry applications. Critical reviews in biotechnology, 37(8), 959-973. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2017.1286449

Shi, H., Zhang, X., Chen, X., Fang, R., Zou, Y., Wang, D. and Xu, W. (2020). How ultrasound combined with potassium alginate marination tenderizes old chicken breast meat: Possible mechanisms from tissue to protein. Food Chemistry, 328, p.127144. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127144

Shi, H., Zhou, T., Wang, X., Zou, Y., Wang, D. and Xu, W. (2021). Effects of the structure and gel properties of myofibrillar protein on chicken breast quality treated with ultrasound-assisted potassium alginate. Food Chemistry, 358, p.129873. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129873

Solanki, G. and Solanki, R., 2012. Alginate Dressings, an Overview. International Journal of Biomedical Research, 3(1), 24-28.

Strano, M.C., Altieri, G., Admane, N., Genovese, F. and Di Renzo, G.C. (2017). Advance in citrus postharvest management: diseases, cold storage and quality evaluation. Citrus pathology, 10, 139-159. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/66518

Szekalska, M., Puciłowska, A., Szymańska, E., Ciosek, P. and Winnicka, K. (2016). Alginate: current use and future perspectives in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. International Journal of Polymer Science, 1-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7697031

Szekalska, M., Sosnowska, K., Zakrzeska, A., Kasacka, I., Lewandowska, A. and Winnicka, K. (2017). The influence of chitosan cross-linking on the properties of alginate microparticles with metformin hydrochloride—In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Molecules, 22(1), p.182. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22010182

Teshima, R., Kawano, Y., Hanawa, T. and Kikuchi, A. (2020). Preparation and evaluation of physicochemical properties of novel alkaline calcium alginate hydrogels with carbonated water. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 31(12), 3032-3038. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.5027

The National Health Service Act 2006. Salt: The Facts. How much salt? Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-types/salt-nutrition/ (Accesses 26 June 2022).

Tokatlı, K. and Demirdöven, A. (2020). Effects of chitosan edible film coatings on the physicochemical and microbiological qualities of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). Scientia Horticulturae, 259, 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108656

Vieira, T.M., Moldão-Martins, M. and Alves, V.D. (2021). Composite coatings of chitosan and alginate emulsions with olive oil to enhance postharvest quality and shelf life of fresh figs (Ficus carica L. cv.‘Pingo De Mel’). Foods, 10(4), p.718. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040718

Wang, S., Vincent, T., Roux, J.C., Faur, C. and Guibal, E. (2017). Pd (II) and Pt (IV) sorption using alginate and algal-based beads. Chemical Engineering Journal, 313, 567-579. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.12.039

Xu, L., Zhang, B., Qin, Y., Li, F., Yang, S., Lu, P., Wang, L. and Fan, J. (2020). Preparation and characterization of antifungal coating films composed of sodium alginate and cyclolipopeptides produced by Bacillus subtilis. International journal of biological macromolecules, 143, 602-609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.051

Yadav, A., Kumar, N., Upadhyay, A., Sethi, S. and Singh, A. (2022). Edible coating as postharvest management strategy for shelf‐life extension of fresh tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.): An overview. Journal of Food Science, 1-35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.16145

Zakharov, N.A., Koval, E.M., Aliev, A.D., Shelekhov, E.V., Kiselev, M.R., Matveev, V.V., Orlov, M.A., Demina, L.I., Zakharova, T.V. and Kuznetsov, N.T. (2021). Calcium Hydroxyapatite/Potassium Alginate Organomineral Composites: Synthesis and Properties. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 66(3), 305-312. doi: https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036023621030219

Zhang, M. and Zhao, X. (2020). Alginate hydrogel dressings for advanced wound management. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 162, 1414-1428. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.311

Leave a comment