Citrus fruits, including orange (Citrus sinensis), lemon (Citrus limon), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi), and lime (Citrus aurantifolia), and mandarin (Citrus reticulata), are among the most widely cultivated and economically important fruit crops worldwide. Belonging to the Rutaceae family, these fruits primarily grow in tropical and subtropical regions (Topi, 2020). Citrus fruits are valued for their juice, peels, and essential oils, which possess notable antimicrobial and nutritional properties (Jana et al., 2020). Citrus trees are evergreen and are widely cultivated in countries such as China, Nepal, India, Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, Egypt, Argentina, the United States, Iran, Italy, and Spain (Curk et al., 2016).

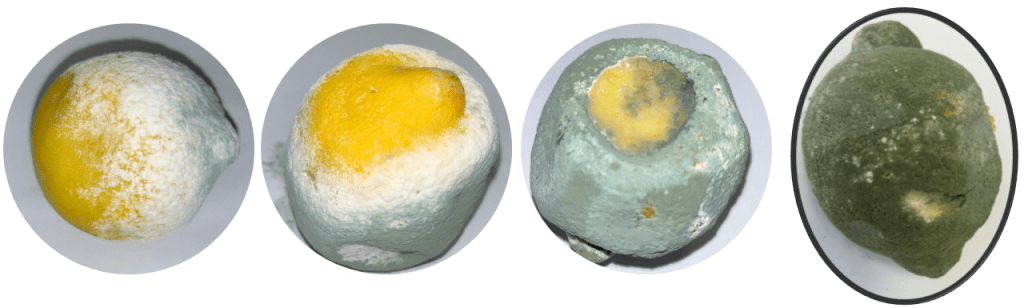

Figure 1: Postharvest citrus losses caused by Penicillium infestation during storage.

Postharvest losses in Citrus are mainly caused by the fruit’s metabolic disorders and diseases, which can lead to severe economic losses ranging from 30% to 50% of total production within 60 days of storage (Bazioli et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2020). The major postharvest fungal diseases affecting Citrus fruits are green mould and blue mould, caused by Penicillium digitatum and P. italicum, respectively. Among these, Penicillium digitatum alone is responsible for over 80% of postharvest losses (Figure 1) under high moisture conditions (Bazioli et al., 2019). Fruits often become contaminated during harvesting, packing, storage, and transportation, primarily due to skin damage (Strano et al., 2022).

In the storage of Citrus fruits, fungicides remain the primary method for controlling green mould caused by the necrotrophic fungus P. digitatum. However, this approach is unsustainable and poses risks to human health (Cheng et al., 2019). Alternatively, BECs incorporated with essential oils have proven effective in protecting fruits against fungal infestation and mechanical damage while improving the marketability of Citrus fruits (Maftoonazad and Ramaswamy, 2019; El-Gioushy et al., 2022).

Chitosan, a popular eco-friendly, biodegradable polysaccharide, is widely used as a safe preservative due to its excellent film-forming properties. It helps extend shelf life and reduces qualitative decay of fresh fruits and vegetables during the postharvest period (Zhang et al., 2021).

This post aims to address the research question: “Are chitosan-based edible coatings effective in controlling Penicillium moulds in Citrus fruits?”

Key considerations for choosing BECs before coatings in fruits and vegetables.

ECs can be applied directly to the surface of foods to reduce environmental stresses (Eyiz et al., 2020). To be effective, ECs must meet several criteria: they should be safe for consumption, biodegradable, sustainable, compatible with essential oils (EOs), and comply with both food safety and environmental regulations (Chen et al., 2020; Abdel-Naeem et al., 2021). ECs serve as excellent barriers against gas and moisture exchange, delay fruit ripening and senescence, maintain fruit glossiness, ensure mechanical stability, and inhibit infestation by pests and pathogens (Iñiguez-Moreno et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2022). Moreover, good ECs are expected to have strong compatibility with EOs, which improves their longevity, wetting, and adhesion capabilities over time (Marín et al., 2019). For example, Pirozzi et al. (2020) reported that incorporating EOs into edible films significantly enhances their durability and strength during refrigerated storage compared to films without EOs.

Similarly, the quality of ECs depends on factors such as pH, thickness, viscosity, total viable microbial cells present, and the degree of polymer cross-linking (Iñiguez-Moreno et al., 2021). Consequently, good ECs possess the ability to resist mechanical shocks and abrasion, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of fruits. Additionally, incorporating essential oils (EOs) into edible coatings not only enhances their mechanical strength, water resistance, light-blocking, and thermal resistance properties but also improves their antioxidant and antimicrobial effects (Ebrahimzadeh et al., 2023).

Postharvest Impact and Disease Characteristics of Penicilium Mould in Citrus Fruits

Postharvest losses in Citrus fruits may occur due to two primary factors: physical losses resulting from injuries and diseases, and quality losses caused by metabolic and compositional changes within the fruit itself. Early symptoms of green mould include small, soft, watery spots on the peel accompanied by white cottony growth (Figure 2).

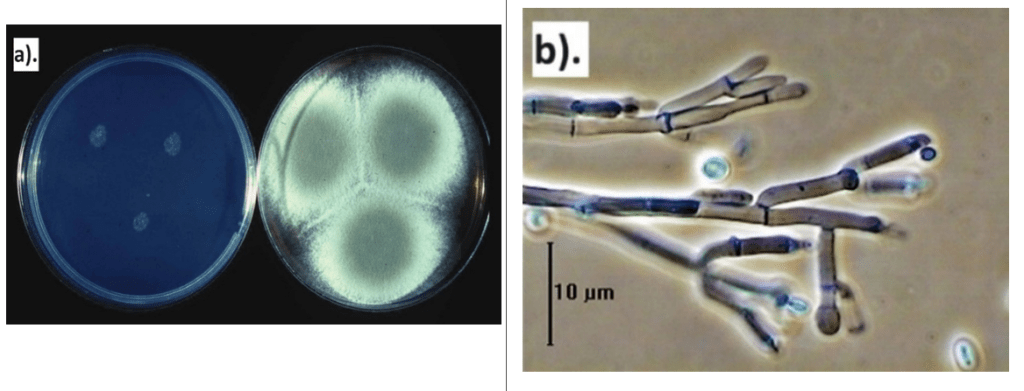

Figure 2: Mycelial Growth and Disease Progression of Penicillium spp. in Stored Citrus.

In severe infestations, fruits can be completely covered by green mould and develop black lesions or spots, leading to desiccation and shrinkage (Figure 2). When incubated for 24–36 hours at 24°C on Malt Extract Agar media, the mould forms a white circular colony (Figure 3a). Under severe conditions, the spot can enlarge by 2–4 cm per day. The colony’s centre produces green asexual spores (conidia) surrounded by thick white mycelium. Consequently, infested fruits rapidly collapse and rot under high humidity, or shrink and mummify under lower humidity levels (Bhatta, 2022; CABI, 2023).

Infected fruits produce white mycelia and green conidia (Figure 3b), which are characteristic symptoms of green mould rot in lemons (Lin et al., 2019). Green mould is a major cause of postharvest losses in lemons and other Citrus fruits, causing approximately 60–80% spoilage under ambient storage conditions. In contrast, Penicillium italicum, the fungal pathogen responsible for blue mould, is more prevalent in cold-stored fruits. Combined infestation by P. digitatum and P. italicum during storage can result in over 90% fruit loss globally during postharvest stages (Li et al., 2020; Strano et al., 2022). Consequently, green mould is considered the largest contributor to postharvest diseases, leading to severe economic losses. Regarding mycotoxin production, P. digitatum is not known to produce patulin, a mycotoxin commonly linked to P. expansum, a necrotrophic pathogen that causes blue mould in fruits such as apples, pears, cherries, and citrus (Pitt, 2014; Li et al., 2020).

Figure 3: a) Penicillium digitatum in culture plate. b). Conidiophores of 7 days old culture of P. digitatum (CABI, 2023).

The mycelium of P. digitatum produces enzymes such as glucose oxidase and catalase, which break down the cell wall structure of fruits and vegetables. This degradation initiates shrinkage, leading to a sunken, mummified appearance of the fruit (Figure 2). Consequently, the infected pericarp and mesocarp cells undergo plasmolysis, resulting in soft, watery rot spots on the fruit (El-Gendi et al., 2021).

Disease Cycle of Penicillium digitatum.

P. digitatum is a mesophilic fungus that survives in the soil of citrus-producing areas from season to season, primarily as conidia. Airborne spores penetrate the rind through wounds and initiate infection. Some infections can also result from damage to the oil glands alone. Additionally, the fungus can enter fruit through certain physiologically induced injuries, such as stem-end rind breakdown and chilling injury (Aglave, 2018; Costa et al., 2019). Generally, in packed containers, the fungus does not spread from rotting fruit to nearby healthy fruit if the rind remains intact. However, in packinghouses, the infection and sporulation cycle can recur frequently throughout the season. Green mould is typically more common in late-season and damaged-rind fruits. It proliferates best at temperatures around 24°C, grows slowly below 10°C and above 30°C, and nearly ceases growth at 1°C (Aglave, 2018). Industrially, especially during the summer months, damage rates during transportation and storage can reach 70–80%, and in extreme cases, up to 100%. This high level of spoilage is primarily attributed to elevated temperatures affecting the fruit from harvest, through farm-level storage and transportation, to warehouse storage (Figure 4a,b).

Figure 4: Severe Penicillium mould spoilage in A) Oranges and B) Limes across the postharvest supply chain.

Sustainable Management of Penicillium Mould

The management of this mould includes careful handling and picking of fruits to minimise the risk of infestation at the farm level (Costa et al., 2019). Sanitary practices are essential to prevent fungal sporulation from diseased fruits and the accumulation of spores on equipment, packaging, and storage facilities during postharvest handling and storage. The formation of mould can also be significantly delayed by rapidly cooling fruits after packaging (Costa et al., 2019; Papoutsis et al., 2019). Additionally, numerous studies have shown that successful prevention of postharvest fungal spoilage in citrus can be achieved by incorporating plant-based essential oils into edible coatings (Bhandari et al., 2022; Salem et al., 2022).

The Biochemical Structure, relation between structures, and properties of Chitosan.

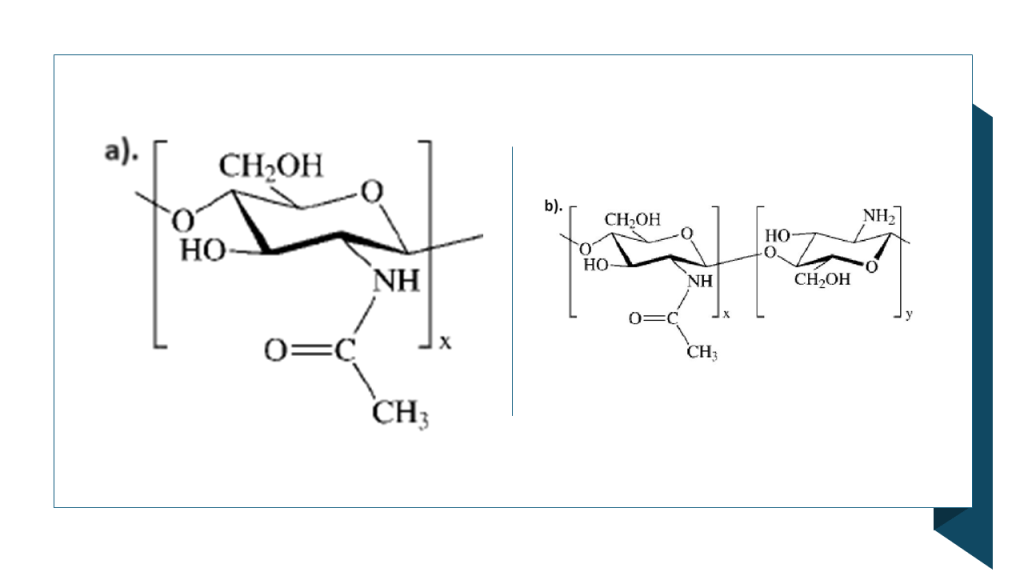

Chemically, chitosan is composed of D-glucosamine units and N-acetyl D-glucosamine, obtained through the partial deacetylation of chitin (Figure 5b). It has a wide range of applications in the food, chemical, medical, and pharmaceutical industries (Muñoz-Tebar et al., 2023).

Figure 5: a). Chemical structure of Chitin; b). Chemical structure of Chitosan (Ibrahim and El-Zairy, 2015).

Chitin is the most prevalent naturally occurring semipermeable biopolymer coating after cellulose and is structurally very similar to cellulose (Figure 5a). It can modify the internal atmosphere of coated fruits by reducing transpiration rates, thereby delaying ripening. Crosslinked chitosan films offer enhanced strength and resistance, making them suitable for handling. Aqueous chitosan coatings and films are transparent, flexible, durable, and provide good oxygen barrier properties (Ebrahimzadeh et al., 2023). Because of their antifungal properties, chitosan edible coatings have significant potential for use in fruits and vegetables to control various pre- and postharvest diseases in fresh produce such as plums, strawberries, oranges, and tomatoes (Chaudhary et al., 2020).

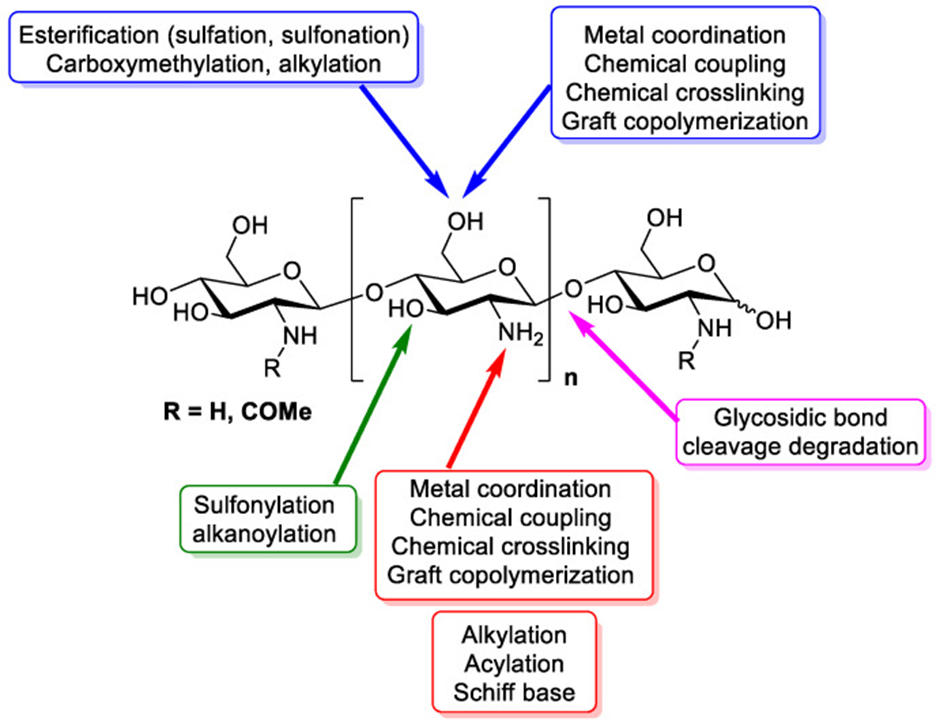

The properties of the functional groups in chitosan’s structure are illustrated in Figure 6. Chitin is generally considered an acetylated polysaccharide composed of repeating units of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine linked by β(1→4) bonds. Chitosan (poly-β(1,4)-2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose) is produced by the deacetylation of chitin through a chemical process (Panahi et al., 2023).

Figure 6: Functional groups present in chitosan structure (Aranaz et al., 2021).

Chitosan can form transparent or slightly yellowish, smooth, cohesive, and flexible coatings with high mechanical resistance compared to other commercial polymers. This is due to its excellent hydrophilic properties, safety, and suitability for a wide range of food products (Muñoz-Tebar et al., 2023). Typically, chitosan concentrations used in coatings range from 1 to 3% (w/v) and are dissolved in an aqueous solution acidified with lactic or acetic acid at concentrations between 1% and 3% (v/v) (Kumar et al., 2020; Hossain et al., 2019; Muñoz-Tebar et al., 2023).

Chitosan edible films can also be combined with plant extracts (essential oils) and other environmentally friendly synthetic materials, such as nanoparticles derived from plant extracts, to enhance their antimicrobial properties (Ali et al., 2022; Hossain et al., 2022).

Biochemical Properties of Chitosan for Edible Coatings and its Application In Citrus Fruits to Control Postharvest Fungal Pathogens.

The presence of functional groups in chitosan, such as hydroxyl (-OH) and amine (-NH₂), are the dominant reactive sites responsible for its antimicrobial activity. This means that the antimicrobial effect of chitosan is stronger when free (-OH) and (-NH₂) groups are present (Nunes et al., 2021). Tayel et al. (2016) investigated the antifungal properties of chitosan using yeast extract–peptone–dextrose agar plates inoculated with 0.1 mL of fungal spore suspension containing 10⁶–10⁷ CFU/mL of both P. digitatum and P. italicum. After 48 hours of incubation at 25 °C, chitosan exhibited inhibitory effects, showing a 20.3 mm inhibition zone for P. digitatum and a minimum fungicidal concentration of 67.5 μg/mL. Similarly, it showed a 21.4 mm inhibition zone for P. italicum and an MFC of 62.5 μg/mL.

The antifungal activity of chitosan was significantly enhanced by incorporating plant extracts. For example, the widest growth inhibition zones for P. digitatum (24.5 mm) and P. italicum (25.2 mm) were observed with Lepidium sativum seed extract. Corresponding MFCs were 32.5 μg/mL against P. digitatum and 27.5 μg/mL against P. italicum (Tayel et al., 2016). However, the growth inhibition zones for both fungi were zero or not detected under some conditions. When coated with chitosan + Lepidium sativum seed extract and with chitosan alone, fungal counts for P. digitatum and P. italicum were 1.9 × 10² CFU/mL and 1.3 × 10² CFU/mL, and 35 × 10³ CFU/mL and 25 × 10³ CFU/mL, respectively. This contrasts with the counts of 28 × 10⁶ CFU/mL for P. digitatum and 31 × 10⁶ CFU/mL for P. italicum in control fruits. These findings suggest that chitosan alone possesses potent antifungal properties against the fungi causing both green and blue mould (Tayel et al., 2016).

Overall, these results indicate that P. italicum is generally more sensitive than P. digitatum, as evidenced by its wider inhibition zones, and lower minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) values (Tayel et al., 2016; Papoutsis et al., 2019).

Figure 7: Development of P. digitatum (A) and P. italicum (B) on infected lemons after 14 days of storage under different treatments: (1) control; (2) commercial antifungal; (3) chitosan coating; (4) chitosan + Lepidium sativum extract (Tayel et al., 2016).

Figure 7 shows a comparison of several coating treatments on lemon fruits infected with P. digitatum and P. italicum. After 14 days of infection, fruits coated with chitosan alone and with a combination of chitosan and L. sativum extract were significantly protected against mould spread. In contrast, fruits without any coating or those treated with a commercial antifungal were almost entirely covered with green and blue mould (Tayel et al., 2016).

Table 1: The impact of different chitosan-based formulation coatings on the progress of Penicillium spoilage in lemon fruits (Tayel et al., 2016).

| Coating Agents | Decayed parts with P. digitatum (mm) | Decayed parts with P. digitatum (mm) | ||||||

| After 3 days | After 7 days | After 10 days | After 14 days | After 3 days | After 7 days | After 10 days | After 14 days | |

| Control | 14.6 | 68.9 | 84.5 | 100 | 11.4 | 61.2 | 82.2 | 100 |

| Chitosan | 4.6 | 8.5 | 19.6 | 34.1 | 3.7 | 8.2 | 14.4 | 18.9 |

| Chitosan+ Lepidium sativum seed extract | 0 (not detected) | 6.1 | 15.3 | 21.6 | 0 (not detected) | 5.4 | 9.9 | 15.5 |

The combined application of chitosan and Lepidium sativum seed extract completely protects coated fruits from fungal decay for up to 3 days. However, the decay rate caused by both Penicillium species increased between 7 and 14 days of storage at room temperature (Table 1) (Tayel et al., 2016).

Table 2: Antifungal activity of chitosan (Chien and Chou, 2006).

| Treatment | Growth Inhibition (%) | ||

| P. digitatum | P. italicum | Botrytis cinerea | |

| Chitosan A | |||

| 0.1% | 75.0 | 76.2 | 48.4 |

| 0.2% | 79.0 | 78.6 | 57.9 |

| Chitosan B | |||

| 0.1% | 50.0 | 71.4 | 34.7 |

| 0.2% | 75.0 | 90.5 | 59.0 |

Table 2 displays the antifungal activity of chitosan A (crab-shell chitosan) and chitosan B (94.20% N-deacetylated chitosan) on the growth of three postharvest fungal pathogens in potato dextrose broth. The inhibition rate of mycelial growth ranged from 34.7% to 90.5%, depending on the fungal pathogen tested, as well as the concentration and type of chitosan coating, compared with the control fruits. It was observed that the growth inhibition of all three fungal pathogens increased as the concentration rose from 0.1% to 0.2%, regardless of the organism or chitosan type. For example, the growth inhibition of chitosan A against P. digitatum increased from 75.0% at 0.1% to 79.0% at 0.2%. Similarly, 0.1% chitosan A showed a higher fungal growth inhibition of 76.2% against the blue mould-causing fungus P. italicum, compared to 71.4% for chitosan B. However, at 0.2%, the antifungal activity of chitosan A was slightly higher against P. digitatum (79.0%) than against P. italicum (78.6%) (Chien and Chou, 2006).

Coating fruits with chitosan ECs is not only effective in preventing postharvest fungal decay but also helps minimize weight loss in fruits and vegetables. For example, the lowest decay rate in fruits was achieved with 0.2% chitosan A, compared to 0.05% and 0.1% concentrations. Additionally, the moisture or weight loss of Tankan oranges was minimized to about 7%, which is more than three times less than that observed with other chitosan-based coatings during storage at 13 °C over 6 weeks. Weight loss in Tankan fruit increased steadily with longer storage times, regardless of the treatment applied. These results suggest that both the type and concentration of chitosan coatings significantly influence fruit deterioration and weight loss during storage. Therefore, chitosan coatings infused with thyme essential oil could be an excellent alternative to chitosan alone for controlling green mould (Chien and Chou, 2006; Kharchoufi et al., 2018).

Table 3: The effect of Chitosan-based edible coatings on the control of different postharvest fungal pathogens in citrus fruits.

| Name | Pathogen | Incorporated with | Results | Concentration | References |

| Citrus Lemon | P. digitatum, and P. italicum | Lepidium sativum seed extract | Prevented coated citrus fruit from decay by green and blue mould for a 2-week storage period. | 20g/L | (Tayel et al., 2016) |

| Citrus tankan | P. digitatum, P. italicum, and Botrytis cinerea. | N-deacetylation | Control mould growth and weight loss in fruits up to 6 weeks. | 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2% chitosan solutions | (Chien and Chou, 2006) |

| Valencia Orange | P. digitatum | Clay Nanocomposite | Complete inhibition of P. digitatum was achieved after 7 days of incubation at 24 °C. | 20 μg/mL | (Youssef and Hashim, 2020) |

| Navel Orange | P. digitatum, P. italicum | Lemongrass EO | Prevent the development of fruit decay due the moulds incidence during 40days of storage at 20°C. | 6 ml/L, 8 ml/L | (El-Mohamedy et al., 2015) |

| Valencia Orange | P. digitatum | – | 100% growth inhibition by chitosan at concentrations at 0.5% incubated at 25°C for 7 days in darkness. | 0.5% | (Panebianco et al., 2014) |

| Mandarin | P. digitatum | Clove oil | The combination of chitosan and clove EO inhibited the mycelial growth more than individual treatments, which led to the release of cellular material and alterations in hyphal morphology. | 1.0% | (Shao et al., 2015) |

El-Mohamedy et al. (2015) demonstrated that the combined use of chitosan and lemongrass essential oil (EO) significantly reduces the growth and spore germination of P. digitatum and P. italicum in orange and lime fruits, compared to the individual application of either chitosan or lemongrass EO alone. Specifically, the combination of chitosan and lemongrass EO at concentrations of 4 g/L and 4 mL/L, respectively, completely inhibited spore germination of both pathogens. These results suggest that an effective combination of EO with chitosan coatings can be safely applied as a fruit coating to control not only green moulds in citrus fruits but also other serious postharvest fungal pathogens (Palou et al., 2015). This finding aligns with the results of Panebianco et al. (2014), who reported complete inhibition of P. digitatum by 0.5% chitosan coatings on Valencia oranges incubated at 25°C for 7 days in darkness (Table 3).

Thus, the combined use of chitosan-based edible coatings and plant-based essential oils, a novel approach for citrus fruits, can effectively enhance the antifungal activity of the coatings, improve fruit shelf-life, and ensure safety for human consumption (Chein et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Green mould caused by P. digitatum is a major threat to Citrus fruits, causing significant economic losses. Conventional fungicide use is unsustainable and poses health risks, highlighting the need for eco-friendly alternatives. Chitosan, a biodegradable and safe polysaccharide, has proven effective as an edible coating to extend shelf life and reduce decay in Citrus fruits. Moreover, combining chitosan with plant-based essential oils enhances antifungal activity against key postharvest pathogens like green and blue mould in the fruits.

References:

Abdel-Naeem, H.H., Zayed, N.E. and Mansour, H.A. (2021). Effect of chitosan and lauric arginate edible coating on bacteriological quality, deterioration criteria, and sensory attributes of frozen stored chicken meat. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 150, p.111928.

Aglave, B. (2018). Citrus. Handbook of plant disease identification and management (pp.164-175). CRC Press.

Ali, S.G., Jalal, M., Ahmad, H., Sharma, D., Ahmad, A., Umar, K. and Khan, H.M. (2022). Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Camellia sinensis and its antimicrobial and antibiofilm effect against clinical isolates. Materials, 15(19), p.6978.

Aranaz, I., Alcántara, A.R., Civera, M.C., Arias, C., Elorza, B., Heras Caballero, A. and Acosta, N. (2021). Chitosan: An overview of its properties and applications. Polymers, 13(19), p.3256.

Bhandari, N., Bika, R., Subedi, S. and Pandey, S. (2022). Essential oils amended coatings in citrus postharvest management. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, p.100375.

Bhatta, U.K. (2022). Alternative management approaches of citrus diseases caused by Penicillium digitatum (green mold) and Penicillium italicum (blue mold). Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, p.833328.

CABI (2023). Penicillium digitatum (green mould). Available From: https://plantwiseplusknowledgebank.org/doi/10.1079/PWKB.Species.39570 (Accessed: 28 July 2025).

Chaudhary, S., Kumar, S., Kumar, V. and Sharma, R. (2020). Chitosan nanoemulsions as advanced edible coatings for fruits and vegetables: Composition, fabrication and developments in last decade. International journal of biological macromolecules, 152, pp.154-170.

Chein, S.H., Sadiq, M.B. and Anal, A.K. (2019). Antifungal effects of chitosan films incorporated with essential oils and control of fungal contamination in peanut kernels. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 43(12), p.e14235.

Chen, F., Zhang, J., Chen, C., Kowaleguet, M.G., Ban, Z., Fei, L. and Xu, C. (2020). Chitosan-based layer-by-layer assembly: Towards application on quality maintenance of lemon fruits. Advances in Polymer Technology, 20, 1-10.

Cheng, H., Mou, Z., Wang, W., Zhang, W., Wang, Z., Zhang, M., Yang, E. and Sun, D. (2019). Chitosan–catechin coating as an antifungal and preservable agent for postharvest satsuma oranges. Journal of food biochemistry, 43(4), p.e12779.

Cheng, Y., Lin, Y., Cao, H. and Li, Z. (2020). Citrus postharvest green mold: recent advances in fungal pathogenicity and fruit resistance. Microorganisms, 8(3), p.449.

Chien, P.J. and Chou, C.C. (2006). Antifungal activity of chitosan and its application to control post‐harvest quality and fungal rotting of Tankan citrus fruit (Citrus tankan Hayata). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 86(12), pp.1964-1969.

Costa, J.H., Bazioli, J.M., de Moraes Pontes, J.G. and Fill, T.P. (2019). Penicillium digitatum infection mechanisms in citrus: What do we know so far?. Fungal biology, 123(8), pp.584-593.

Curk, F., Ollitrault, F., Garcia-Lor, A., Luro, F., Navarro, L. and Ollitrault, P. (2016). Phylogenetic origin of limes and lemons revealed by cytoplasmic and nuclear markers. Annals of botany, 117(4), pp.565-583.

Ebrahimzadeh, S., Biswas, D., Roy, S. and McClements, D.J. (2023). Incorporation of essential oils in edible seaweed-based films: A comprehensive review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 135, pp.43-56.

El-Gendi, H., Saleh, A.K., Badierah, R., Redwan, E.M., El-Maradny, Y.A. and El-Fakharany, E.M. (2021). A comprehensive insight into fungal enzymes: Structure, classification, and their role in mankind’s challenges. Journal of Fungi, 8(1), p.23.

El-Gioushy, S.F., Abdelkader, M.F., Mahmoud, M.H., Abou El Ghit, H.M., Fikry, M., Bahloul, A.M., Morsy, A.R., Abdelaziz, A.M., Alhaithloul, H.A., Hikal, D.M. and Abdein, M.A. (2022). The effects of a gum arabic-based edible coating on guava fruit characteristics during storage. Coatings, 12(1), p.90.

El-Mohamedy, R.S., El-Gamal, N.G. and Bakeer, A.R.T. (2015). Application of chitosan and essential oils as alternatives fungicides to control green and blue moulds of citrus fruits. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 4, pp.629-643.

Eyiz, V., Tontul, İ. and Türker, S. (2020). The effect of edible coatings on physical and chemical characteristics of fruit bars. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 14, pp.1775-1783.

Hossain, F., Follett, P., Salmieri, S., Vu, K.D., Fraschini, C. and Lacroix, M. (2019). Antifungal activities of combined treatments of irradiation and essential oils (EOs) encapsulated chitosan nanocomposite films in in vitro and in situ conditions. International journal of food microbiology, 295, pp.33-40.

Hossain, S.I., Sportelli, M.C., Picca, R.A., Gentile, L., Palazzo, G., Ditaranto, N. and Cioffi, N. (2022). Green Synthesis and Characterization of Antimicrobial Synergistic AgCl/BAC Nanocolloids. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 5(7), pp.3230-3240.

Ibrahim, H.M. and El-Zairy, E.M.R. (2015). Chitosan as a biomaterial—structure, properties, and electrospun nanofibers. Concepts, compounds and the alternatives of antibacterials, 1(1), pp.81-101.

Iñiguez-Moreno, M., Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A. and Calderón-Santoyo, M. (2021). An extensive review of natural polymers used as coatings for postharvest shelf-life extension: Trends and challenges. Polymers, 13, pp.1-31.

Jana, P., Sureshrao, P.A. and Sahu, R.S. (2020). Medicinal and health benefits of lemon. Journal of Science and Technology, 6, pp.16-20.

Kharchoufi, S., Parafati, L., Licciardello, F., Muratore, G., Hamdi, M., Cirvilleri, G. and Restuccia, C. (2018). Edible coatings incorporating pomegranate peel extract and biocontrol yeast to reduce Penicillium digitatum postharvest decay of oranges. Food Microbiology, 74, pp.107-112.

Kumar, S., Mukherjee, A. and Dutta, J. (2020). Chitosan based nanocomposite films and coatings: Emerging antimicrobial food packaging alternatives. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 97, pp.196-209.

Li, B., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Qin, G., Chen, T. and Tian, S. (2020). Molecular basis and regulation of pathogenicity and patulin biosynthesis in Penicillium expansum. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 19(6), pp.3416-3438.

Lin, Y., Fan, L., Xia, X., Wang, Z., Yin, Y., Cheng, Y. and Li, Z. (2019). Melatonin decreases resistance to postharvest green mold on citrus fruit by scavenging defense-related reactive oxygen species. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 153, pp.21-30.

Maftoonazad, N. and Ramaswamy, H.S. (2019). Application and evaluation of a pectin-based edible coating process for quality change kinetics and shelf-life extension of lime fruit (Citrus aurantifolium). Coatings, 9, pp.1-14.

Marín, A., Plotto, A., Atarés, L. and Chiralt, A. (2019). Lactic acid bacteria incorporated into edible coatings to control fungal growth and maintain postharvest quality of grapes. Hortscience, 54, pp.337-343.

Muñoz-Tebar, N., Pérez-Álvarez, J.A., Fernández-López, J. and Viuda-Martos, M. (2023). Chitosan Edible Films and Coatings with Added Bioactive Compounds: Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties and Their Application to Food Products: A Review. Polymers, 15(2), p.396.

Nunes, Y.L., de Menezes, F.L., de Sousa, I.G., Cavalcante, A.L.G., Cavalcante, F.T.T., da Silva Moreira, K., de Oliveira, A.L.B., Mota, G.F., da Silva Souza, J.E., de Aguiar Falcao, I.R. and Rocha, T.G. (2021). Chemical and physical Chitosan modification for designing enzymatic industrial biocatalysts: How to choose the best strategy?. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 181, pp.1124-1170.

Palou, L., Valencia-Chamorro, S.A. and Pérez-Gago, M.B. (2015). Antifungal edible coatings for fresh citrus fruit: A review. Coatings, 5(4), pp.962-986.

Panahi, H.K.S., Dehhaghi, M., Amiri, H., Guillemin, G.J., Gupta, V.K., Rajaei, A., Yang, Y., Peng, W., Pan, J., Aghbashlo, M. and Tabatabaei, M. (2023). Current and emerging applications of saccharide-modified chitosan: a critical review. Biotechnology advances, 66, p.108172.

Panebianco, S., Vitale, A., Platania, C., Restuccia, C., Polizzi, G. and Cirvilleri, G. (2014). Postharvest efficacy of resistance inducers for the control of green mold on important Sicilian citrus varieties. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 121, pp.177-183.

Papoutsis, K., Mathioudakis, M.M., Hasperué, J.H. and Ziogas, V. (2019). Non-chemical treatments for preventing the postharvest fungal rotting of citrus caused by Penicillium digitatum (green mold) and Penicillium italicum (blue mold). Trends in Food Science & Technology, 86, pp.479-491.

Pirozzi, A., Del Grosso, V., Ferrari, G. and Donsì, F. (2020). Edible coatings containing oregano essential oil nanoemulsion for improving postharvest quality and shelf life of tomatoes. Foods, 9(11), p.1605.

Pitt, J.I. (2014). PENICILLIUM | Penicillium and Talaromyces:: Introduction. Food Science, 14, p.6-13.

Salem, M.F., Abd-Elraoof, W.A., Tayel, A.A., Alzuaibr, F.M. and Abonama, O.M. (2022). Antifungal application of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with pomegranate peels and nanochitosan as edible coatings for citrus green mold protection. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 20(1), p.182.

Shao, X., Cao, B., Xu, F., Xie, S., Yu, D. and Wang, H. (2015). Effect of postharvest application of chitosan combined with clove oil against citrus green mold. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 99, pp.37-43.

Strano, M.C., Altieri, G., Allegra, M., Di Renzo, G.C., Paterna, G., Matera, A. and Genovese, F. (2022). Postharvest technologies of fresh citrus fruit: Advances and recent developments for the loss reduction during handling and storage. Horticulturae, 8(7), p.612.

Tayel, A.A., Moussa, S.H., Salem, M.F., Mazrou, K.E. and El‐Tras, W.F. (2016). Control of citrus molds using bioactive coatings incorporated with fungal chitosan/plant extracts composite. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 96(4), pp.1306-1312.

Topi, D. (2020). Volatile and chemical compositions of freshly squeezed sweet lime (Citrus limetta) juices. The Journal of Raw Materials to Processed Foods, 1(1), pp.22-27.

Yadav, A., Kumar, N., Upadhyay, A., Sethi, S. and Singh, A. (2022). Edible coating as postharvest management strategy for shelf‐life extension of fresh tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.): An overview. Journal of Food Science, pp.1-35.

Youssef, K. and Hashim, A.F. (2020). Inhibitory Effect of Clay/Chitosan Nanocomposite against Penicillium digitatum on Citrus and Its Possible Mode of Action. Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences, 13(3), pp.349 – 355.

Zhang, X., Ismail, B.B., Cheng, H., Jin, T.Z., Qian, M., Arabi, S.A., Liu, D. and Guo, M. (2021). Emerging chitosan-essential oil films and coatings for food preservation-A review of advances and applications. Carbohydrate Polymers, 273, p.118616.

Leave a comment