Figure 1. A fully grown Thyme plant with flowers (Kim et al., 2022).

Thyme (Thymus vulgaris), commonly known as garden thyme, is a small, bushy, and evergreen perennial herb (Figure 1) of the mint family, Lamiaceae. Native to the Mediterranean region, this plant exhibits either an upright or creeping growth habit, depending on the species (Hammoudi et al., 2022). Thyme has been widely used since ancient times due to its numerous health benefits, which are attributed to the rich concentration of bioactive compounds in its dried leaves, flowering tops, and essential oils (Hammoudi et al., 2022). In addition, it serves as a culinary ingredient to flavour meats such as boar, lamb, and rabbit, as well as in liqueurs and cheese. As one of the most significant medicinal aromatic plants, thyme’s economic importance is largely derived from its essential oils, which are extensively used in the food and pharmaceutical industries (Nieto, 2020). The major components of thyme oil include thymol, p-cymene, γ-terpinene, and linalool (Table 1).

Table 1. Major biochemical components in the leaves of Thymus vulgaris.

| Compounds | Quantity (%) |

| Thymol | 23-60 |

| p-Cymene | 8-44 |

| γ-Terpinene | 18-50 |

| Linalool | 3-4 |

| Carvacrol | 2-8 |

| β-Caryophyllene | 3.1 |

| α-Pinene | 1.9 |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1.3 |

Source: Adapted from Satyal et al. (2016); Nieto (2020); and Hammoudi et al. (2022).

Thymus vulgaris has been used since time immemorial as a traditional herbal remedy to treat conditions including alopecia, dermatophyte infections, dental plaque, bronchitis, cough, gastrointestinal distress, and inflammatory skin disorders, in addition to its applications in the food industry (Kowalczyk et al., 2020). The essential oil (EO) of T. vulgaris exhibits a broad spectrum of biological activities, including antifungal, antibacterial, antiviral, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory effects, which underpins its extensive use for medicinal purposes (Hammoudi et al., 2022).

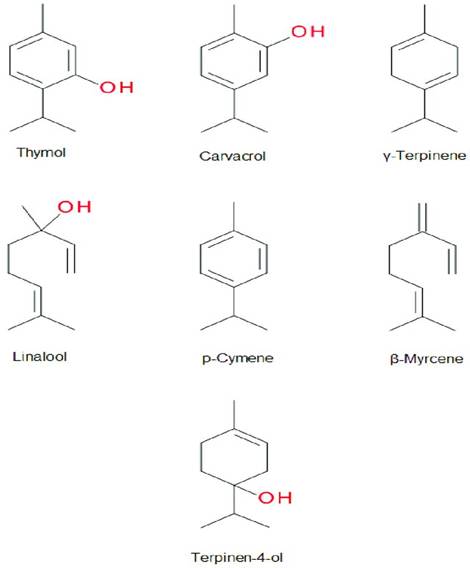

The main components of thyme essential oil are the phenolic monoterpenes thymol (2-isopropyl-5-methylphenol) and carvacrol (2-methyl-5-(propan-2-yl)phenol). Thyme EO is also a source of various other bioactive compounds, including phenolic acids, such as caffeic, p-coumaric, rosmarinic, carnosic, and quinic acid (as well as cinnamic, caffeoylquinic, and ferulic acids); flavonols (e.g., quercetin-7-O-glucoside); flavones (e.g., apigenin); and flavanones (e.g., naringenin) (Satyal et al., 2016; Baj et al., 2020). Thymol is a colourless, crystalline monoterpene phenol characterised by a strong, pungent odour and high solubility in alcohol. In contrast, carvacrol is a colourless to pale yellow viscous liquid with a smell reminiscent of thymol; it is highly soluble in organic solvents such as acetone, ethanol, and diethyl ether (Nazzaro et al., 2017). The biochemical structures of thymol, carvacrol, and other major thyme EO components are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Chemical structures of the major components in Thymus vulgaris essential oil (Kowalczyk et al., 2020).

The antifungal activity of thyme EO is primarily attributed to the hydroxyl groups present in its phenolic terpenes. Specifically, thymol and carvacrol, biosynthesized from p-cymene, exert a significant antifungal effect by disrupting the fungal cell membrane through interactions with its sterols (Kowalczyk et al., 2020; Das et al., 2021). Carvacrol binds to these membrane sterols, causing structural damage and eventual cell death. Although the positional isomers thymol and carvacrol have their hydroxyl groups in different locations, their similar overall structure enables them to cause analogous membrane damage. A related membrane-targeting mechanism has been observed for linalool, which also compromises fungal cell stability and inhibits biofilm formation. Due to these structural characteristics, thyme EO and its constituents are highly effective at inhibiting fungal growth and the production of associated mycotoxins (Bound et al., 2016; Kowalczyk et al., 2020). This potency has been demonstrated in studies against post-harvest spoilage fungal pathogens, including Penicillium digitatum, where thyme EO and its main components (carvacrol, thymol, γ-terpinene, and linalool) remarkably inhibit spore germination and mycelial growth. The mechanism involves the rupture of the plasma membrane, leading to increased extracellular conductivity and the leakage of cellular contents (Camele et al., 2012; Memar et al., 2017; Chou et al., 2023).

As discussed in our previous blog on chitosan-based edible coatings here, chitosan effectively controls postharvest fungal spoilage in citrus fruits. Building on this, this desk-based study proposes that both chitosan and thyme EO are effective agents for use as edible coatings and films in the food industry. Notably, chitosan coatings incorporated with thyme EO demonstrate stronger antifungal properties compared to non-composite chitosan coatings. Their combination at optimised concentrations could yield a more potent antifungal effect, capable of controlling not only green mould in fruits and vegetables but also a broader spectrum of postharvest fungal pathogens. These findings align with several studies indicating that the lipophilic bioactive compounds in essential oils play a major role in inhibiting fungal spore germination. For instance, thyme EO has proven effective not only in controlling green mould decay in fruits but also in managing other postharvest fungal diseases, including grey mould, blue mould, and sour rot, due to its potent antifungal properties (Satyal et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2020).

Applications of Thyme EO in the Food Industry

In recent years, thyme essential oil EO has been extensively studied for its potential applications in food and beverages. It has been established as an effective natural preservative due to its ability to control foodborne microorganisms (Gonçalves et al., 2017). In fact, thyme EO is recognised as a functional food. A growing body of evidence indicates that thyme and its derivatives provide significant health benefits that extend beyond their role as flavour adjuncts. Consequently, based on these benefits which surpass basic nutrition, thyme and its derivatives meet the criteria to be classified as functional foods (Gonçalves et al., 2017; Serrano et al., 2020).

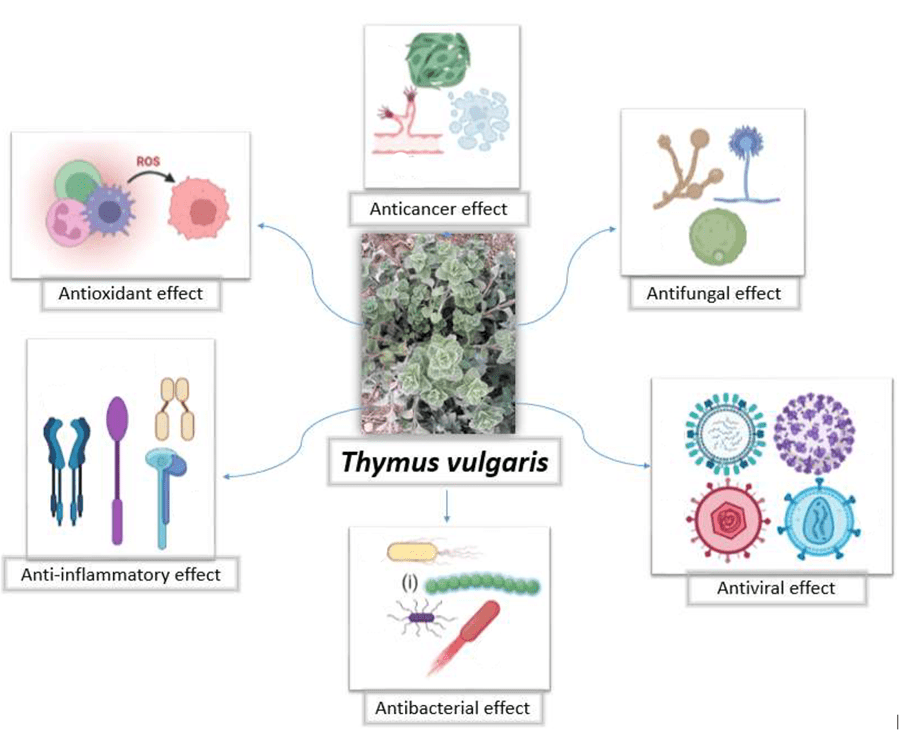

Furthermore, Thyme EO offers a range of beneficial health effects (Figure 3), including anti-diabetic, antipathogenic, cardio-protective, anti-atherogenic, cancer-preventive, digestive stimulant, and anti-inflammatory properties (Gonçalves et al., 2017; Nieto, 2020; Hammoudi et al., 2022). Among these, its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities have received considerable attention for their role in improving food quality. In the meat industry, thyme EO is primarily employed as a natural antioxidant and preservative to prolong shelf-life. Numerous recent studies have demonstrated that incorporating thyme EO into both raw and cooked meat products can effectively inhibit lipid oxidation and rancidity during refrigerated and frozen storage, thereby maintaining the sensory and microbiological quality of meat and fish for extended periods (Guerrero et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021; Asuoty et al., 2023). For instance, Mahmoud et al. (2014) reported that immersing carp fish fillets in a 1% thymol solution significantly reduced mesophilic bacterial counts and extended the product’s shelf life from 4 to 12 days under storage at 5°C.

Figure 3. Key biological activities and health benefits of Thymus vulgaris and its essential oil (Hammoudi et al., 2022).

In many studies, thyme EO has demonstrated efficacy against several postharvest fungal pathogens and bacteria, including Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Fusarium spp., yeasts, Enterobacteriaceae, and Staphylococcus aureus. Its mechanism of action primarily involves disrupting the integrity and permeability of the microbial cell membrane, which leads to the inhibition of enzymatic activity and eventual cell death. As a result, thyme EO is increasingly being utilised as a natural protective agent in a variety of food products such as meat, oranges, berries, and semi-processed foods, often incorporated into edible coatings for fresh produce (Ahmadian et al., 2020; Radünz et al., 2020; Pinto et al., 2021).

The antioxidant activity of thyme leaves is also leveraged for food preservation. For instance, incorporating thyme leaves into goat feed enhanced the bromatological qualities and oxidative stability of the resulting cheese (Nieto, 2020). Similarly, supplementing dairy cow diets with thyme has been shown to benefit animal health while also improving milk yield and its physicochemical composition. However, the quantity of thyme added to animal feed must be carefully regulated to avoid adverse effects, such as intoxication or abortion, which can result from the overuse of its potent phenolic compounds (Kalaitsidis et al., 2021; Czech et al., 2023).

The Fungicidal Mechanism of Thyme Essential Oil against Moulds

Thyme EO is composed of approximately 13 major chemical compounds, which represent about 97.0% of its total volume. These constituents can be divided into four primary categories: monoterpenes (e.g., γ-terpinene), monoterpenoids (e.g., linalool), phenols (e.g., thymol), and sesquiterpenes. These groups account for 47.94%, 16.11%, 29.2%, and 3.69% of the total oil, respectively, and together comprise more than 75% of its chemical profile (Wan et al., 2019; Qi et al., 2023). Among these, thymol exhibits the strongest antifungal activity, surpassing both the complete thyme EO and its other principal compounds. The antifungal activity of linalool, a monoterpenoid, is comparatively higher than that of the monoterpene group. In contrast, γ-terpinene, a monoterpene, possesses the lowest efficacy in inhibiting fungal spore germination (Qi et al., 2023). For instance, a thymol emulsion concentration of 0.52 mg/mL inhibited approximately 90% of Penicillium digitatum spore germination, while 0.76 mg/mL was required for P. italicum. In comparison, a higher concentration of the complete thyme oil emulsion was needed to achieve the same degree of inhibition (Qi et al., 2023).

In fact, a number of studies have proposed that the antifungal mechanism of thymol is primarily due to its hydroxyl group and a system of delocalised electrons. These structural features destabilise the microbial cytoplasmic membrane and reduce the pH gradient across it by acting as a proton exchanger (Marchese et al., 2016). This disruption depletes the ATP pool and collapses the proton motive force, ultimately leading to cell death (Tian et al., 2022).

In contrast, p-cymene, a biosynthetic precursor to thymol, exhibits lower antifungal activity. Its chemical structure consists of a benzene ring that is para-substituted with methyl and isopropyl groups but lacks a hydroxyl group. Conversely, linalool possesses a hydroxyl group which facilitates its penetration across the cytoplasmic membrane, accounting for its stronger antifungal activity compared to monoterpenes like γ-terpinene and p-cymene (Memar et al., 2017). For instance, Hossain et al. (2019) found that while p-cymene itself exhibits only mild antifungal activity, it acts synergistically with carvacrol, an isomer of thymol also found in thyme EO, to combat fungal pathogens such as Penicillium spp. and Fusarium spp. These findings suggest that incorporating whole thyme EO into polysaccharide matrices, such as chitosan, could act synergistically to enhance antifungal efficacy against P. digitatum and other mycotoxin-producing fungi (Memar et al., 2017; Soppelsa et al., 2023).

Table 2. Efficacy of thyme essential oil (EO) against Penicillium species in fruits.

| Fruits | Application Method | Dose (v/v or w/v) | Target Pathogens | Key Findings | References |

| Orange | Vapor phase in polypropylene film | 51.7 µL/L; stored 12 days at 7 °C | P. digitatum, P. italicum | Reduced infected wounds, mycelial growth rate, and spore production in inoculated oranges. | Pinto et al. (2021) |

| Grapes | Sprayed suspension | 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/mL | Penicillium spp. | Significant reduction in fungal growth and decay development at 1.5 mg/mL. | Ghuffar et al. (2021) |

| Mexican lime | Carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) coating | Thyme EO (0.2%) in CMC (1.5%) | P. digitatum, P. italicum | Controlled external mycelial growth in both in vitro and in vivo environments. | Abbasi et al. (2023) |

| Orange juice | Direct addition | 250, 500, and 1000 µL/L | P. digitatum, P. italicum | Complete inhibition of fungal growth and spore germination at all tested concentrations. | Boubaker et al. (2016) |

| Oranges (volatiles) | Vapor phase in sealed environment | 10, 100, and 1000 µL/L (volatile exposure) | P. digitatum, P. italicum | Complete inhibition of fungal growth achieved at 1000 µL/L, or via volatiles from 10 µL in a 5 cm diameter Petri dish. | Plaza et al. (2004) |

| Oranges | Direct application (assay) | 250, 500, and 1000 mg/L | P. digitatum, P. italicum | Completely inhibited radial growth and spore germination at concentrations of 500 and 1000 mg/L. | Jafarpour et al. (2006) |

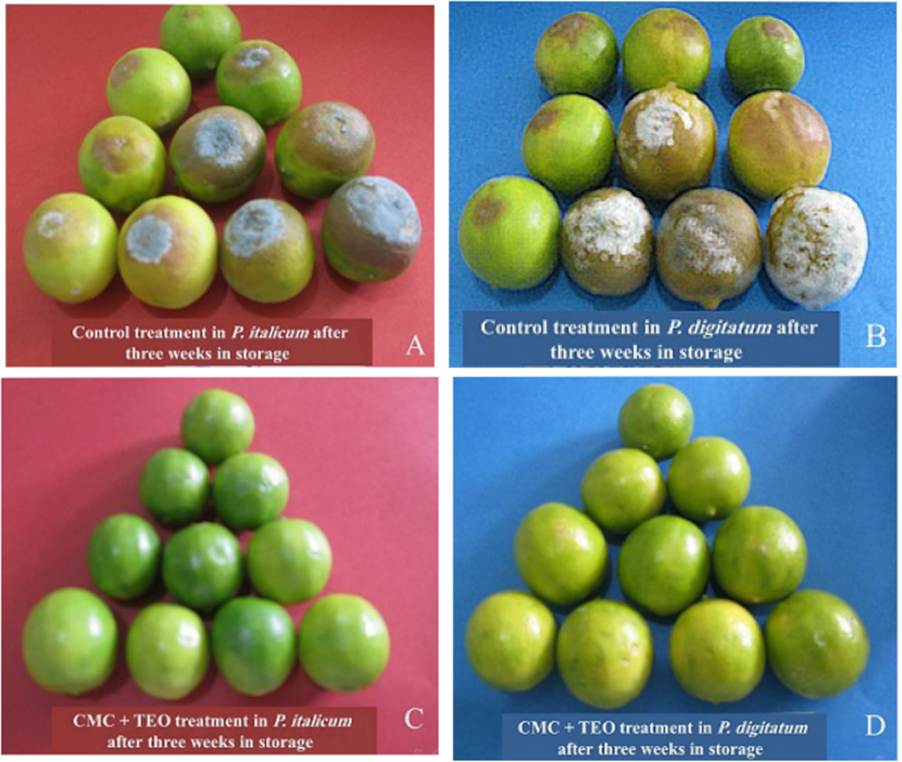

Pinto et al. (2021) investigated the efficacy of thyme oil (Thymus vulgaris L.) in controlling Penicillium decay and extending the shelf-life of oranges during cold storage. Treatment with thyme EO vapour, delivered within a polypropylene film, significantly reduced the percentage of infected wounds on inoculated fruits stored for 12 days at 7 °C (Table 2). The study also found that the vapour treatment did not adversely affect the organoleptic attributes of the oranges, including juice taste, colour, and flavour. Therefore, active packaging incorporating EO, either in liquid or vapour forms, could be effectively employed alongside edible coatings, like chitosan and alginate, in the citrus industry. This approach shows promise for extending shelf-life for the fresh market and controlling postharvest decay (Pinto et al., 2021; Abbasi et al., 2023). These results align with those of Abbasi et al. (2023), who reported that a coating containing 0.2% thyme EO and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) effectively inhibited the external mycelial growth of both green and blue mould on Mexican limes in both in vitro and in vivo environments (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Efficacy of a CMC coating incorporating thyme EO in controlling green mould (P. digitatum) and blue mould (P. italicum) on Mexican limes (Abbasi et al., 2023).

The coating combining thyme EO and CMC demonstrated the highest antifungal activity in vitro compared to either component applied individually. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed that the combined CMC and thyme EO treatment altered the morphology of both P. digitatum and P. italicum hyphae, resulting in wrinkled and distorted surfaces. As a result, incorporating thyme EO into a polysaccharide-based edible coating is preferable to applying it separately for preventing postharvest infections in citrus and non-citrus fruits, as this combination is likely to yield more effective results (Ghuffar et al., 2021; Abbasi et al., 2023). In fact, thymol damages the fungal cell membrane by interacting with ergosterol, disrupts ionic balances (e.g., Ca²⁺ and H⁺), and alters mycelial morphology. These actions ultimately lead to the mis-localisation of chitin within the hyphae (Nazzaro et al., 2017; Pavoni et al., 2019). These findings indicate that thymol, the primary active ingredient in thyme oil, is principally responsible for its antifungal properties. It is therefore widely accepted that among thyme EO constituents, phenolic compounds like thymol exhibit the highest antifungal efficacy, followed by oxygenated terpenes and terpenoids (Memar et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2019).

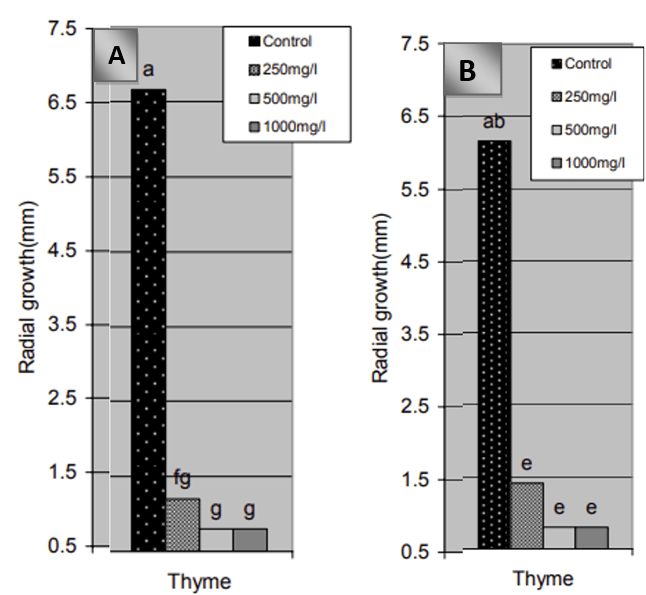

Another study revealed that thyme EO completely inhibited the mycelial growth of P. digitatum and P. italicum at a concentration of 1000 µL/L, while spore germination was inhibited at 500 µL/L in vitro. This effect is attributed to the oil’s strong antifungal and antispore activities (Boubaker et al., 2016). This result is consistent with the findings of Plaza et al. (2004), who reported that thyme EO could serve as an alternative to synthetic fungicides for controlling postharvest pathogens in citrus. They observed complete inhibition of fungal growth either at 1000 µL/L or via volatile compounds emitted from 10 µL of EO in a 5 cm diameter Petri dish. Similarly, Jafarpour et al. (2006) found that thyme EO at concentrations of 500 and 1000 mg/L almost completely inhibited the radial growth and spore germination of P. digitatum and P. italicum incubated at 25–28 °C for 8 days (Figure 5). Collectively, these studies indicate that thyme EO, being natural and non-toxic to humans, could effectively substitute for harmful synthetic fungicides in postharvest treatments.

Figure 5. Inhibitory effects of thyme essential oil (EO) on the radial growth of (A) Penicillium italicum and (B) Penicillium digitatum at various concentrations (Jafarpour et al., 2006).

Hence, incorporating thyme EO into chitosan coatings enhances fungistatic activity against P. digitatum. As green mould is the most destructive postharvest disease of lemons, this combination offers significant potential for improving postharvest protection and extending shelf-life (Kowalczyk et al., 2020; Das et al., 2021).

The Synergistic Mechanism Between Thyme Essential Oil and Chitosan for Improved Edible Coating Structures

Antimicrobial biopolymer coatings are highly desirable for a variety of applications in the food sector. Research into the preparation and characterisation of chitosan-based coatings aims to understand how their biochemical composition interacts with thyme EO, thereby influencing their antibacterial efficacy and physical properties. According to Sedlaříková et al. (2019), the stability and compatibility of essential oil within a chitosan matrix can be enhanced by incorporating the stabilising agent Tween 80 alongside thyme EO as the active ingredient. Tween 80, a hydrophilic surfactant, facilitates the transport of the oil to the film surface. Furthermore, the addition of thyme EO to chitosan significantly reduces the particle size in coating solutions, concurrently increasing film thickness and enhancing the barrier properties of the resulting coatings. Thyme EO demonstrates excellent antimicrobial properties even at low concentrations; consequently, chitosan films incorporated with thyme EO represent a promising tool for antimicrobial packaging applications (Correa‐Pacheco et al., 2017; Memar et al., 2017; Sedlaříková et al., 2019). Moreover, several studies have indicated that the lipophilic bioactive compounds in essential oils play a major role in hindering fungal spore germination. Their lipophilic nature enables them to penetrate the phospholipid bilayer of the fungal cell membrane, ultimately inducing membrane rupture (Sharma et al., 2017). For instance, Qi et al. (2023) observed that this disruption causes a massive loss of cytoplasmic material, leading to cell shrinkage and the formation of rough, corrugated surfaces. This results in severe morphological deformation, collapse, and deterioration of the cell wall in both spores and hyphae.

Furthermore, these composite coatings enhance the shelf-life and marketability of lemons. They improve fruit glossiness, which attracts consumer attention compared to desiccated and dull fruits. Modern consumers are increasingly conscious of visual attributes such as size, colour, and firmness, while also prioritising internal qualities like flavour, aromatic volatile compounds, and health-functional components. Consequently, purchasing decisions are based on a combination of appearance, quality, and value for money (Serna-Escolano et al., 2021; Sánchez-Bravo et al., 2022). Thus, the novel approach of combining chitosan-based edible coatings with thyme EO may effectively enhance antifungal activity, extend the shelf-life of fruits and vegetables, and ensure safety for human consumption (Chein et al., 2019).

In conclusion, thyme essential oil EO, renowned for its potent antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, holds significant promise in postharvest disease management. Its incorporation into edible coatings, particularly in combination with chitosan, enhances antifungal and antibiofilm activities against postharvest fungal pathogens such as P. digitatum, Fusarium spp. and Botrytis effectively extending the shelf-life of fresh produce. Beyond its preservative effects, thyme EO contributes to the development of functional, biodegradable packaging materials with improved mechanical and barrier properties. This study highlights the potential of thyme EO-based coatings as a natural, sustainable alternative to synthetic fungicides, offering innovative solutions for postharvest management while reinforcing the broader applications of thyme EO in food preservation and safety.

References

Abbasi, M., Dastjerdi, A.M., Seyahooei, M.A., Shamili, M. and Madani, B. (2023). Postharvest control of green and blue molds on Mexican lime fruit caused by Penicillium species using Thymus vulgaris essential oil and carboxy methyl cellulose. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 130(5), pp.1017-1026.

Asuoty, M.S., Fayza, A.I. and Abou-Arab, N.M. (2023). Effect of Thyme Oil and Acetic Acid on The Quality and Shelf Life of Fresh Meat. Journal of Advanced Veterinary Research, 13(6), pp.1079-1083.

Ahmadian, A., Seidavi, A. and Phillips, C.J. (2020). Growth, carcass composition, haematology and immunity of broilers supplemented with sumac berries (Rhus coriaria L.) and thyme (Thymus vulgaris). Animals, 10(3), p.513.

Baj, T., Biernasiuk, A., Wróbel, R. and Malm, A. (2020). Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. Open Chemistry, 18(1), pp.108-118.

Boubaker, H., Karim, H., El Hamdaoui, A., Msanda, F., Leach, D., Bombarda, I., Vanloot, P., Abbad, A., Boudyach, E.H. and Aoumar, A.A.B. (2016). Chemical characterization and antifungal activities of four Thymus species essential oils against postharvest fungal pathogens of citrus. Industrial Crops and Products, 86, pp.95-101.

Bound, D.J., Murthy, P.S. and Srinivas, P. (2016). 2, 3-Dideoxyglucosides of selected terpene phenols and alcohols as potent antifungal compounds. Food Chemistry, 210, pp.371-380.

Camele, I., Altieri, L., De Martino, L., De Feo, V., Mancini, E. and Rana, G.L. (2012). In vitro control of post-harvest fruit rot fungi by some plant essential oil components. International journal of molecular sciences, 13(2), pp.2290-2300.

Chou, M.Y., Andersen, T.B., Mechan Llontop, M.E., Beculheimer, N., Sow, A., Moreno, N., Shade, A., Hamberger, B. and Bonito, G. (2023). Terpenes modulate bacterial and fungal growth and sorghum rhizobiome communities. Microbiology Spectrum, 11(5), pp.e01332-23.

Correa‐Pacheco, Z.N., Bautista‐Baños, S., Valle‐Marquina, M.Á. and Hernández‐López, M. (2017). The effect of nanostructured chitosan and chitosan‐thyme essential oil coatings on Colletotrichum gloeosporioides growth in vitro and on cv Hass avocado and fruit quality. Journal of Phytopathology, 165(5), pp.297-305.

Czech, A., Klimiuk, K. and Sembratowicz, I. (2023). The effect of thyme herb in diets for fattening pigs on their growth performance and health. Plos one, 18(10), p.e0291054.

Das, S., Singh, V.K., Dwivedy, A.K., Chaudhari, A.K. and Dubey, N.K. (2021). Insecticidal and fungicidal efficacy of essential oils and nanoencapsulation approaches for the development of next generation ecofriendly green preservatives for management of stored food commodities: an overview. International Journal of Pest Management, pp.1-32.

Ghuffar, S., Irshad, G., Naz, F. and Khan, M.A. (2021). Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides. Green Processing and Synthesis, 10(1), pp.021-036.

Gonçalves, N.D., de Lima Pena, F., Sartoratto, A., Derlamelina, C., Duarte, M.C.T., Antunes, A.E.C. and Prata, A.S. (2017). Encapsulated thyme (Thymus vulgaris) essential oil used as a natural preservative in bakery product. Food Research International, 96, pp.154-160.

Guerrero, A., Ferrero, S., Barahona, M., Boito, B., Lisbinski, E., Maggi, F. and Sañudo, C. (2020). Effects of active edible coating based on thyme and garlic essential oils on lamb meat shelf life after long‐term frozen storage. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 100(2), pp.656-664.

Hammoudi, D.H., Krayem, M., Khaled, S. and Younes, S. (2022). A focused insight into thyme: Biological, chemical, and therapeutic properties of an indigenous Mediterranean herb. Nutrients, 14(10), p.2104.

Hossain, F., Follett, P., Salmieri, S., Vu, K.D., Fraschini, C. and Lacroix, M. (2019). Antifungal activities of combined treatments of irradiation and essential oils (EOs) encapsulated chitosan nanocomposite films in in vitro and in situ conditions. International journal of food microbiology, 295, pp.33-40.

Jafarpour, B., Rastegar, M.F., Jahanbakhsh, V., Azizi, M. and Farzad, S. (2006), August. Inhibitory Effect Of Some Medicinal Plants’essential Oils On Postharvest Fungal Disease Of Citrus Fruits. In XXVII International Horticultural Congress-IHC2006: International Symposium on The Role of Postharvest Technology, 768, pp.279-286.

Kalaitsidis, K., Sidiropoulou, E., Tsiftsoglou, O., Mourtzinos, I., Moschakis, T., Basdagianni, Z., Vasilopoulos, S., Chatzigavriel, S., Lazari, D. and Giannenas, I. (2021). Effects of cornus and its mixture with oregano and thyme essential oils on dairy sheep performance and milk, yoghurt and cheese quality under heat stress. Animals, 11(4), p.1063.

Kim, M., Sowndhararajan, K. and Kim, S. (2022). The chemical composition and biological activities of essential oil from Korean native thyme Bak-Ri-Hyang (Thymus quinquecostatus Celak.). Molecules, 27(13), p.4251.

Kowalczyk, A., Przychodna, M., Sopata, S., Bodalska, A. and Fecka, I. (2020). Thymol and thyme essential oil—new insights into selected therapeutic applications. Molecules, 25(18), p.4125.

Marchese, A., Orhan, I.E., Daglia, M., Barbieri, R., Di Lorenzo, A., Nabavi, S.F., Gortzi, O., Izadi, M. and Nabavi, S.M. (2016). Antibacterial and antifungal activities of thymol: A brief review of the literature. Food chemistry, 210, pp.402-414.

Memar, M.Y., Raei, P., Alizadeh, N., Aghdam, M.A. and Kafil, H.S. (2017). Carvacrol and thymol: strong antimicrobial agents against resistant isolates. Reviews and Research in Medical Microbiology, 28(2), pp.63-68.

Mohammed, M.A., Syeda, J.T., Wasan, K.M. and Wasan, E.K. (2017). An overview of chitosan nanoparticles and its application in non-parenteral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics, 9(4), p.53.

Nazzaro, F., Fratianni, F., Coppola, R. and De Feo, V. (2017). Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals, 10(4), p.86.

Nieto, G. (2020). A review on applications and uses of thymus in the food industry. Plants, 9(8), p.961.

Pavoni, L., Maggi, F., Mancianti, F., Nardoni, S., Ebani, V.V., Cespi, M., Bonacucina, G. and Palmieri, G.F. (2019). Microemulsions: An effective encapsulation tool to enhance the antimicrobial activity of selected EOs. Journal of drug delivery science and technology, 53, p.101101.

Pinto, L., Cefola, M., Bonifacio, M.A., Cometa, S., Bocchino, C., Pace, B., De Giglio, E., Palumbo, M., Sada, A., Logrieco, A.F. and Baruzzi, F. (2021). Effect of red thyme oil (Thymus vulgaris L.) vapours on fungal decay, quality parameters and shelf-life of oranges during cold storage. Food Chemistry, 336, p.127590.

Plaza, P., Torres, R., Usall, J., Lamarca, N. and Vinas, I. (2004). Evaluation of the potential of commercial post-harvest application of essential oils to control citrus decay. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 79(6), pp.935-940.

Qi, X., Zhong, S., Schwarz, P., Chen, B. and Rao, J. (2023). Mechanisms of antifungal and mycotoxin inhibitory properties of Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil and their major chemical constituents in emulsion-based delivery system. Industrial Crops and Products, 197, p.116575.

Radünz, M., dos Santos Hackbart, H.C., Camargo, T.M., Nunes, C.F.P., de Barros, F.A.P., Dal Magro, J., Sanches Filho, P.J., Gandra, E.A., Radünz, A.L. and da Rosa Zavareze, E. (2020). Antimicrobial potential of spray drying encapsulated thyme (Thymus vulgaris) essential oil on the conservation of hamburger-like meat products. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 330, p.108696.

Satyal, P., Murray, B.L., McFeeters, R.L. and Setzer, W.N. (2016). Essential oil characterization of Thymus vulgaris from various geographical locations. Foods, 5(4), p.70.

Sedlaříková, J., Janalíková, M., Rudolf, O., Pavlačková, J., Egner, P., Peer, P., Varaďová, V. and Krejčí, J. (2019). Chitosan/thyme oil systems as affected by stabilizing agent: Physical and antimicrobial properties. Coatings, 9(3), p.165.

Serrano, A., González-Sarrías, A., Tomás-Barberán, F.A., Avellaneda, A., Gironés-Vilaplana, A., Nieto, G. and Ros-Berruezo, G. (2020). Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of regular consumption of cooked ham enriched with dietary phenolics in diet-induced obese mice. Antioxidants, 9(7), p.639.

Sharma, S., Barkauskaite, S., Duffy, B., Jaiswal, A.K. and Jaiswal, S. (2020). Characterization and antimicrobial activity of biodegradable active packaging enriched with clove and thyme essential oil for food packaging application. Foods, 9(8), p.1117.

Soppelsa, S., Van Hemelrijck, W., Bylemans, D. and Andreotti, C. (2023). Essential Oils and Chitosan Applications to Protect Apples against Postharvest Diseases and to Extend Shelf Life. Agronomy, 13(3), p.822.

Tian, F., Woo, S.Y., Lee, S.Y., Park, S.B., Zheng, Y. and Chun, H.S. (2022). Antifungal Activity of Essential Oil and Plant-Derived Natural Compounds against Aspergillus flavus. Antibiotics, 11(12), p.1727.

Wan, J., Zhong, S., Schwarz, P., Chen, B. and Rao, J. (2019). Physical properties, antifungal and mycotoxin inhibitory activities of five essential oil nanoemulsions: Impact of oil compositions and processing parameters. Food Chemistry, 291, pp.199–206.

Yuan, L., Feng, W., Zhang, Z., Peng, Y., Xiao, Y. and Chen, J. (2021). Effect of potato starch-based antibacterial composite films with thyme oil microemulsion or microcapsule on shelf life of chilled meat. LWT- Food Science and Technology, 139, p.110462

Leave a comment