Implementing a HACCP plan is not just a regulatory requirement—it’s a commitment to delivering safe, high-quality food to every consumer.

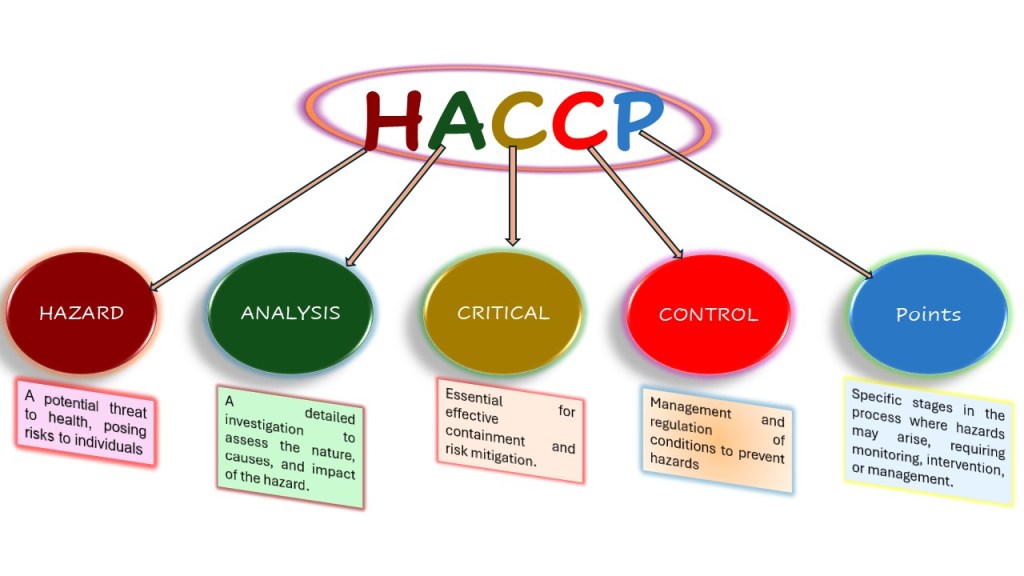

HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points), a food safety management system, is based on seven key principles to maintain food safety in retail stores, food service operations, and processing plants. The HACCP system is a proactive food safety approach designed to prevent, reduce, or eliminate chemical, biological, and physical hazards, ensuring the highest level of food safety. It includes detailed record-keeping to demonstrate compliance and facilitate effective hazard management. By identifying, evaluating, and controlling significant food safety risks across the entire supply chain—from farm to fork—HACCP relies on a deep understanding of cause-and-effect relationships, a cornerstone of Total Quality Management (FAO, 2001). If a problem arises and control is lost, it is quickly detected and corrected to ensure that unsafe or contaminated food does not reach customers. When implementing HACCP, microbiological testing is rarely an efficient method for monitoring critical control points (CCPs) in the HACCP system because it takes too long to get results. Instead, physical and chemical tests, along with visual checks, are typically more effective for real-time monitoring of CCPs. However, microbiological criteria remain valuable for verifying the overall effectiveness of the HACCP system in ensuring food safety (FDA, 1997).

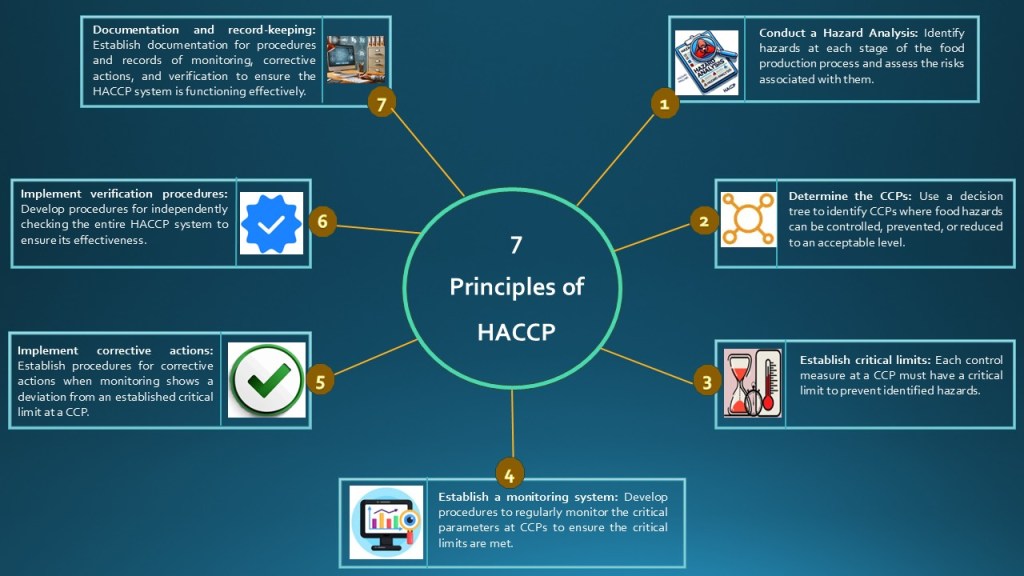

The Seven Principles of HACCP System.

HACCP plans are based on seven key principles (Figure 1) to ensure food safety in retail food stores, food service operations, and food processing plants. These principles, in chronological order, include identifying hazards, determining CCPs, establishing safety limits, monitoring processes, taking corrective actions, verifying procedures, and maintaining documentation and record-keeping. If something goes wrong and control is lost, the issue is quickly identified and corrected to prevent unsafe food from reaching consumers.

Figure 1: Seven principles of HACCP for building a robust HACCP system in an industrial setting.

- Conduct a Hazard Analysis:

This stage involves brainstorming potential hazards at every step of the production process. Hazard analysis is a multi-step process that identifies and evaluates potential biological, chemical, or physical hazards that could cause illness or injury if not properly controlled. This process involves three key steps:

- Hazard Identification: Examining all aspects of production to identify possible sources of contamination. The HACCP team reviews all ingredients, production activities, equipment used, storage and distribution methods, and the intended consumers. This includes assessing raw materials, potential contaminants, steps that eliminate pathogens, storage conditions, packaging methods, and any history of foodborne illnesses linked to the product. Moreover, historical data on past safety issues with similar products can also provide valuable insights.

- Hazard Evaluation: After identifying potential hazards, the team must assesses their severity and likelihood of occurrence. Severity refers to the seriousness of health consequences if exposed to the hazard, including short-term and long-term effects. Likelihood is determined based on experience, epidemiological data, and scientific literature. The evaluation considers how the food is prepared, stored, and transported, as well as the vulnerability of consumers. Factors such as processing conditions, intended use, and potential health risks to targeted customers (e.g., young children, elderly individuals, or immunocompromised individuals) help determine which hazards must be addressed in the HACCP plan. Furthermore, some hazards may be naturally controlled by prerequisite programs such as strict purchasing specifications, suppliers approval, antimicrobial ingredients, strictly adhering to standard operating procedures (SOPs), good manufacturing practices (GMP), and hygiene protocols, particularly in areas where food is exposed post-processing.

- Hazard Control Measures: Once hazards are identified and evaluated, the HACCP team establishes control measures to prevent, eliminate, or reduce risks to an acceptable level.

By systematically identifying, evaluating, and controlling hazards, HACCP ensures food safety throughout the production process, reducing risks and protecting public health (FDA, 1997).

2. Determine Critical Control Points (CCPs):

A CCP is a specific step in the food production process where control can be applied to prevent, eliminate, or reduce a food safety hazard to an acceptable level, and hence, identifying CCPs is crucial to ensuring food safety, as they help control hazards that could lead to illness or injury if left unchecked. Each food production facility must develop a written HACCP plan for every product whenever a hazard analysis identifies one or more food safety hazards that are reasonably likely to occur. Determining CCPs involves assessing potential hazards and identifying the specific steps where control measures are essential for safety. A CCP decision tree (Figure 2) is often used to help determine CCPs based on the hazard analysis conducted by the HACCP team, taking into account facility layout, equipment, ingredient selection, and processing methods.

Figure 2: Decision tree for the identification of CCPs (Adapted from FAO, 2001).

Examples of CCPs in food processing include, but are not limited to:

Cooking temperature: Applying heat to destroy harmful microorganisms.

Stabilisation: Controlling cooling processes to prevent bacterial growth.

Drying: Removing moisture and water activity level to inhibit microbial activity.

Fermentation: Using controlled microbial activity to create safe food products. For example, food pH drops rapidly during fermentation, inhibiting pathogenic microbes and extending shelf life while ensuring safety (Fernandez & Marette, 2017).

Pasteurisation: Using heat treatment to reduce pathogen levels, typically involving heating at 93°C ± 2°C for 15–30 seconds or above 120°C for 3–10 seconds. This process achieves a 97.3%–99.9% disinfection rate but may degrade bioactive compounds and alter the nutritional properties of drinks (Ağçam et al., 2018).

High‐pressure processing (HPP): High-pressure processing (400–600 MPa) is a non-thermal method for microbial inactivation, typically applied for 1.5–6 minutes in industrial settings (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards, 2022). Unlike traditional heat-based preservation techniques, HPP effectively eliminates harmful microorganisms while maintaining the sensory and nutritional quality of food products. The effectiveness of HPP varies depending on the type of microorganism. Moulds, yeasts, and parasites require 200–400 MPa, while bacteria are inactivated at 300–600 MPa. More resistant spores need pressures exceeding 600 MPa at 60°C, with a typical treatment duration of 5–15 minutes (Brockhaus et al., 2022).

Acid Rinses: Lowering pH levels in foods or drinks to control bacterial growth below pH 4, as most bacteria are neutrophiles, growing best at a pH close to 7.0. However, acidophiles (LAB) are exceptions, as they grow optimally at a pH near 3.0 and are generally not pathogenic to humans.

Metal Detection: Screening for physical hazards, particularly metals such as ferrous, non-ferrous, and stainless steel, in finished products.

Since different food processing facilities may vary in layout, equipment, ingredients, and processes, the identified CCPs can differ between establishments, even when producing similar food products. Therefore, a well-documented and carefully developed CCP system is essential for maintaining food safety standards.

3. Establish Critical Limits:

Critical limits are the maximum or minimum values that must be maintained at each CCP to prevent, eliminate, or reduce hazards to an acceptable level. A critical limit is a parameter, whether biological, chemical, or physical, that must be controlled at a CCP to prevent, eliminate, or reduce a food safety hazard. Critical limits help distinguish between safe and unsafe conditions during food production. Each CCP must have clearly defined critical limits that ensure the food safety hazard is controlled. These limits are established to meet performance standards set by authorities like the FSIS, BRCGS, and any other relevant regulations.

Control Measures and Critical Limits

Each CCP will have one or more control measures to ensure that hazards are addressed. For each control measure, there will be corresponding critical limits. These limits can be based on factors such as temperature, time, physical dimensions, moisture level, Water activity (aw), pH level, salt concentration, preservatives, and viscosity. In fact, critical limits must be based on scientific evidence, not on assumption. Critical limits ensure food safety by establishing precise, measurable criteria for controlling hazards during the food production process.

4. Establish Monitoring Procedures:

Monitoring procedures involve the regular observation or measurement of each CCP to ensure that it remains within the established critical limits (CL). Monitoring can be done continuously or intermittently, depending on the process and available resources. Continuous monitoring is preferred, but if not possible, intermittent checks must be frequent enough to maintain control.

Monitoring Procedures:

Continuous Monitoring: Ideal for many physical and chemical processes, continuous monitoring provides real-time data. For example, temperature and time in the thermal processing of low-acid canned foods can be continuously recorded on temperature charts. If any deviations are observed (e.g., the temperature falls below the required level or the time is insufficient), corrective actions can be taken immediately, and the affected product can be isolated.

Non-continuous Monitoring: When continuous monitoring is not feasible, periodic checks should be performed at a frequency that ensures the CCP remains under control. For example, pH measurement can be done continuously in liquids, or samples may be taken for testing at defined intervals.

The three main purposes of monitoring are:

Tracking the process: It helps ensure that the CCP remains under control. If monitoring indicates a trend towards losing control, corrective actions can be taken before a deviation occurs.

Detecting deviations: Monitoring helps identify when a CCP exceeds or fails to meet its critical limit, triggering the need for corrective actions.

Providing documentation: Monitoring generates records that serve as evidence for verification and demonstrate that the process is being effectively controlled.

Key Aspects of Monitoring:

Personnel Training: Proper assignment and training of monitoring personnel are critical to ensuring that procedures are followed correctly. This training should ensure that staff can detect potential issues early and take necessary actions.

Calibration and Accuracy: Monitoring equipment must be regularly calibrated to ensure that the data it provides is accurate.

Documentation: All monitoring activities should be documented, with records signed and dated by the responsible person to ensure accountability. This documentation will be essential for future verification and audits.

Challenges with Microbiological Testing:

Microbiological tests are not ideal for continuous monitoring due to their time-consuming nature and the difficulty in detecting contaminants quickly. Instead, physical and chemical measurements are typically preferred, as they provide faster results and are more effective in ensuring the control of microbiological hazards. For example, pasteurized milk or drinks safety is assessed by monitoring the time and temperature of the heating process rather than testing the milk for pathogens after the fact.

5. Establish Corrective Actions:

Corrective actions are essential when deviations from critical limits or unforeseen hazards occur in the food safety process. These actions ensure that unsafe products do not reach consumers and that the control measures for CCPs are maintained. The written HACCP plan must specify the corrective actions that should be taken if a deviation from a critical limit happens. The team responsible for corrective actions should be well-versed in the process, product, and HACCP plan. In certain cases, experts may need to be consulted to review the situation and help decide how to manage the non-compliant product. If a deviation occurs that isn’t covered by a predefined corrective action, or if an unforeseen hazard arises, the following steps should be taken:

Determine and Correct the Cause: It is important to identify and address the root cause of the deviation to prevent recurrence.

Disposition of Non-Compliant Product: The affected product must be evaluated and safely disposed of or corrected, ensuring no unsafe product reaches the consumer.

Ensure Control of CCP: Corrective actions must restore control of the CCP and ensure that the process returns to the established safety parameters.

Modification of the HACCP Plan: If necessary, the HACCP plan should be modified to address new hazards or changes to critical limits, ensuring continuous food safety.

Corrective Action(s): When monitoring reveals a deviation from the critical limits, corrective actions must be taken immediately to bring the process back under control. These actions should be documented for verification purposes, ensuring that appropriate measures were taken to maintain food safety. By establishing effective monitoring procedures, facilities can ensure that CCPs are consistently controlled, hazards are mitigated, and food safety is maintained throughout the production process. Each corrective action should be clearly defined for every CCP in the HACCP plan. This plan should include the steps to take when a deviation occurs, identify the responsible individuals for implementing corrective actions, and ensure that records are kept of the actions taken.

6. Establish Verification Procedures:

Verification procedure is crucial to validate whether the HACCP plan is functioning correctly and that the system is operating as intended, which includes:

Plan Validation: Before the HACCP system is fully implemented, the plan must be validated to ensure that it is scientifically and technically sound. This includes confirming that all identified hazards can be controlled effectively by the implemented plan. For example, to validate the cooking process for beef patties, scientific studies and in-plant evaluations are necessary to verify that the time and temperature will effectively eliminate pathogenic microorganisms.

Ongoing Validation: After initial validation, the HACCP plan should be periodically re-validated when significant changes occur, such as, unexplained system failures, changes in product, process, or packaging, and identification of new hazards.

Comprehensive Verification: Comprehensive verification of the HACCP system should be conducted periodically by an unbiased, independent authority, such as by internal personnel, third-party experts-, and regulatory agencies. These activities are essential for maintaining the integrity of the HACCP system and ensuring continuous food safety compliance. This includes technical evaluations of the hazard analysis, an on-site review of flow diagrams, and the review of records. A comprehensive verification is independent of routine verification activities and ensures that the plan is controlling the identified hazards. If deficiencies are found during the review, the HACCP team will make necessary modifications to the plan.

7. Establish record-keeping and documentation procedures.

An effective recordkeeping system is essential for documenting the operation of a HACCP system and ensuring its ongoing compliance. Records must provide written evidence of the various activities that take place within the HACCP system, offering a clear history of its operation. Additionally, well-maintained records are essential for Due Diligence Defense, which can be used as evidence of compliance with food safety regulations, such as the Food Safety Act 1990 in the UK.

Key Components of Recordkeeping:

- Hazard Analysis Summary: A documented summary of the hazard analysis process.

- HACCP Plan: The written plan outlining the critical control points, hazards, and control measures.

- Supporting Documentation: Documents that provide evidence of the processes, procedures, and compliance measures.

- Daily Operational Records: These records reflect the daily operations and monitoring at each CCP.

- Proper record-keeping is critical in the HACCP system, ensuring that all activities are documented for verification and traceability. It provides evidence that the system is functioning as intended and that proper control measures are in place to manage food safety risks.

Key Records to be Maintained:

- Hazard Analysis Summary: This includes the rationale behind the identification of hazards and the control measures adopted for their management.

- HACCP Plan: The formal plan detailing the steps in the process, identified hazards, and control measures.

- HACCP Team Listing: A list of HACCP team members and their assigned responsibilities.

- Food Description: Information about the product, its distribution, intended use, and target consumers.

- Verified Flow Diagram: A diagram that illustrates the production process and identifies critical control points.

Companies must maintain records related to GMP, GHP, and CCPs monitoring, including deviations and corrective actions. Additionally, documentation of the original HACCP study, such as hazard identification and the selection of critical limits, is essential. Both manual and electronic records are acceptable, provided they are appropriate for the size and nature of the operation. Proper recordkeeping ensures compliance with food safety regulations and supports the effective monitoring of HACCP systems to consistently control food safety hazards.

References:

Ağçam, E., Akyıldız, A. and Dündar, B., 2018. Thermal pasteurization and microbial inactivation of fruit juices. In Fruit juices (pp. 309-339). Academic Press.

Brockhaus, B. (2022). What is HPP? All the relevant information about High Pressure Processing. Available from: https://www.thyssenkrupp-industrial-solutions.com/high-pressure-processing/en/what-is-hpp (Accessed 01 December 2024).

EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ Panel), Koutsoumanis, K., Alvarez‐Ordóñez, A., Bolton, D., Bover‐Cid, S., Chemaly, M., Davies, R., De Cesare, A., Herman, L., Hilbert, F. and Lindqvist, R., 2022. The efficacy and safety of high‐pressure processing of food. EFSA Journal, 20(3), p.e07128.

F. A. O. (2001). Manual on the application of the HACCP system in Mycotoxin prevention and control. Retrieved From: https://www.fao.org/4/Y1390E/y1390e00.htm Accessed February 28, 2025.

FDA (1997). HACCP Principles & Application Guidelines. Retrieved From: https://www.fda.gov/food/hazard-analysis-critical-control-point-haccp/haccp-principles-application-guidelines (Accessed 14 March 2025).

Fernandez, M.A. and Marette, A., 2017. Potential health benefits of combining yogurt and fruits based on their probiotic and prebiotic properties. Advances in Nutrition, 8(1), pp.155S-164S.

Leave a comment